Teaching with Contemporary Art

Connecting (from a Safe Distance)

Student artwork by Annabel W., inspired by Lucas Blalock.

In late February 2020, I noticed that I had been keeping a tab open on my web browser, one that was tracking the spread of the novel coronavirus through China. At the time, it still seemed the new virus might be like SARS or MERS but not as bad as Ebola. I told myself that it wouldn’t come to North America, ignorantly convincing myself that such things don’t happen here. And then, of course, it did.

Earlier in the semester, before distance learning became the way I teach my classes, my students and I had been talking about the joys of drawing and looking at the works of diverse artists, from the collaboration between Raymond Pettibon and Marcel Dzama to the abstract compositions created by Louise Despont. In a still life lesson, we looked at how Daniel Gordon’s photographs turned the idea of a “still life” inside out. Just before the schools closed in mid-March, I’d begun pushing my students toward more conceptual work, and we were getting ready for a large unit on love, consumption, and empathy. For inspiration, we’d been looking at the work of Mary Mattingly and Do Ho Suh. I was cruising, like an Art21 honor student.

Then, it all shut down—but something else opened up.

As February turned into March, I began considering the fact that schools might close and have to convert to some kind of distance teaching model. I’d never taught a distance learning course, and the ones I’d taken, back in 2005, asked students to do little more than read the chapter and answer the questions at the end of that chapter. I didn’t want to teach that way. Instead, I began thinking about what I’d be capable of conveying through Zoom sessions, what was essential, and what would be things my students would actually want to do. Fortunately—and I know this isn’t the case for many schools—my students had access to the technology required for this method. This moment of planning, like so many during this pandemic, highlighted the deep inequities in America’s educational system. Knowing that not all of my students would have access to, say, acrylic paint and stretched canvas, I focused on drawing materials: pens, pencils, and paper.

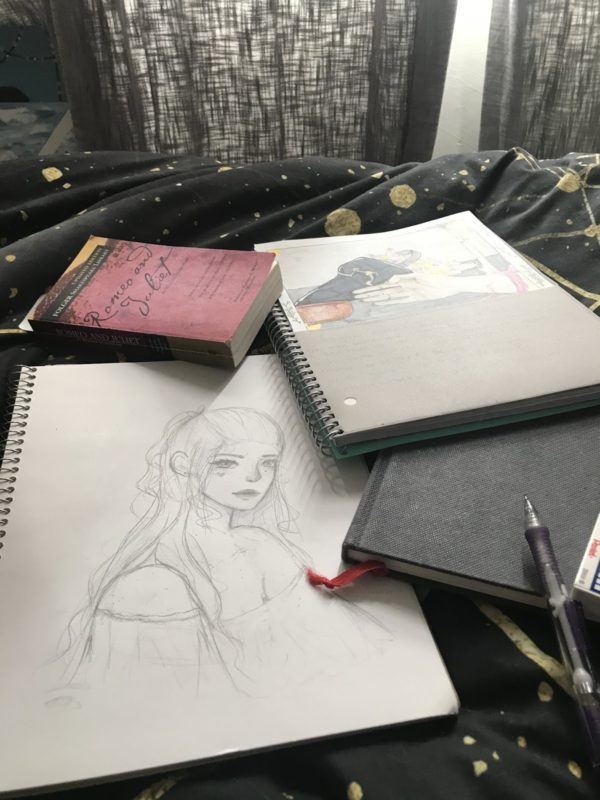

Student Abigail M.’s home work space.

Inspired by artists like William Kentridge, Sol LeWitt, and Tom Friedman, I thought about ways to make drawings that were quick, somewhat absurd, and driven more by creative thinking and experience than by observation. To that end, I put together a list of drawing prompts, such as:

- Go to your refrigerator and find something interesting to draw. Then, go find something from your bedroom to draw on the same piece of paper. Then, do this with something from your bathroom.

- Create a still-life drawing using only straight lines.

- Create a drawing using only your bicycle.

- Draw 60 one-minute drawings during a one-hour session (borrowing from Peter London’s excellent book, No More Secondhand Art).

I love these kinds of absurdist prompts, which have roots in Dada and Fluxus, and I felt that they’d keep the students rolling for a while. Soon, though, I grew restless: I wanted to use physical distance as a creative tool. I began to consider ways in which distance could lead students to engage with contemporary art in a way that pushed their preconceptions of what art is.

Student photography by Isabelle.

During my first year as an Art21 Educator, in 2016, alumni teachers in the program spoke often of the strong influence of Oliver Herring and how his TASK parties provided an open invitation for students to question traditional avenues for creative expression. As Herring says, “Everyone is a creative agent, so, independent of what your interests are, you can bring that to the table.” My new colleagues at Art21 encouraged me to host a TASK party as an entry point for students to participate in contemporary art. For further reinforcement, at the Art21 Educators Summer Institute, we experienced a highly memorable evening with Matt Roche and Jaimie Warren, the creative power-duo behind the artist-led variety show, Whoop Dee Doo. Like Herring’s tasks, Whoop Dee Doo performances are collaborative and, quite often, joyously absurd. I left the Institute fired up to make tasks, to whoop it up…but once I returned home, I never followed through, afraid of getting so much stuff at the store and, I guess, wasting too much tape.

Which brings me back to now, the spring of 2020, social distancing, and the desire to connect. While the recent drawing tasks that I came up with seemed clever, they still seemed too traditional to reach my goal of connecting with my physically distanced students. Still, the more I used the word task, the closer I got to thinking about Herring, his TASK parties, and the need for my students to make a joyful sound. The challenges I presented to my students soon moved away from traditional making and into areas of performance, documentation, and collaboration. I broadened the task list, adding challenges that weren’t rooted in traditional art making. Our tasks began to look more like the following:

- Think of something that you’re really good at and that you can do right now. Go do it and document it, however you see fit.

- Find five really strange things in your home. Take extremely close-up pictures of them. Save, post, and share the images.

- Think of an object that you really don’t like. Imagine a home for the object and create an image of that scene.

- Go for a walk and photograph as many abandoned gloves as you find.

- Throw a temper tantrum for a full 60 seconds. Then, take a selfie.

In the spirit of Herring’s tasks, the list of challenges for my students was online and editable, and each day I would encourage them to add new tasks for each other. As they completed tasks, they added their documentation to a shared class blog. With this structure, we were up and running. Each time I refreshed my browser, I saw the results of new tasks: students making sculptures out of books and dirty laundry, presenting notes of gratitude to their sisters, staging photo-shoots with their dogs, and making poems on their Scrabble boards. To encourage them to move further away from material constraints, I introduced them to the playful works of John Baldessari and Miranda July & Harrell Fletcher, and we talked about Liz Magor and the importance of having a studio, a creative space in each of their homes. Eventually, students from other classes and even teachers at my school began contributing to the task list and blog. Even my eight-year-old daughter helped me. Amid the madness, I found avenues toward joy.

Student artwork by Trevor M.

By early April, it became clear that we wouldn’t return to having classes in the school building before the end of the year. Deep sadness welled up inside me as I thought about on-campus aspects that make teaching a joy: the casual moments shared with students and colleagues, the artistic epiphanies that students occasionally stumble upon, the absurd moments, the laughter, the bad coffee in the faculty room, the thank-you notes that appear in my mailbox around graduation time, and graduation itself. No Internet TASK party can take the place of those and so many other things. As I face the remainder of the school year, however, I also have a sense that when I finally can be back in my classroom, face-to-face with my students, I will have learned profound ways in which to be bolder, better, and more joyous as an educator.

And I didn’t have to go buy a bunch of tape.