Teaching with Contemporary Art

A Year’s Worth of ‘Outcomes’ were centered around ‘Place’

Student work by Cole Hartman

The Art21 Educators program was essential in helping me develop new unit work for my students. During our Summer Institute in 2021, artist Tanya Aguiñga asked: “What is a Border?” That question became the starting point for me to create a unit for my drawing and art appreciation courses at South Seattle College. I also followed that question when my student Fennie and I talked with artist/cartoonist Zeke Peña for an artist speaker series that I organized. Zeke’s work about the Rio Grande River, arbitrary borders, and the erasure of histories linked to our own local story about the Duwamish River. We followed the conversation with an activity where students created reportage-style sketches alongside a writer interviewing local river activist Paulina López, who spoke to us about the resilience and community advocacy of the human residents of South Park most directly impacted by urban and legacy toxicity. We learned from Paulina that there is a constant need to advocate for health justice, and that some of the most inspired and powerful voices are those of youth in South Seattle. That one question led to so many valuable, engaging forms of artistic practice and interrogation.

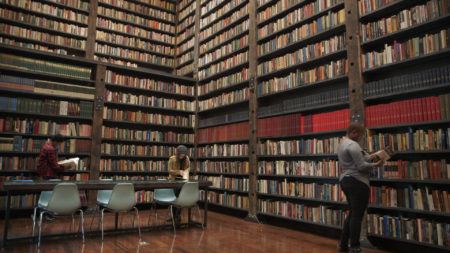

Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” episode, “Investigation.” © ART21, Inc. 2014.

At about the same time, fellow educators in my mentor group, Debra and Amy, were also thinking about ‘place’ to frame their units. Amy and her students documented places on their campus in Roanoke, Virginia, by making clay impressions for small relief prints inspired by Nicole Seisler’s work. Amy noted that some were imprints from the nose of a sculpture monument on campus, and I like imagining these objects as a counter-monument made by students. We’ve talked about the ‘gift economy’ in our small Art21 group, and about how Robin Wall Kimmerer describes service berries and their abundance showering us with goodness and gifts, not just to humans but to many nonhuman kin. I see how our discussions connect with the clay ‘gifts’ that Amy’s students make. Amy says she loves “how pieces of experiences reemerge, and introductions to new things come together for even better ideas!” Amy’s abundance of energy, enthusiasm, and playfulness creates a sense of belonging, and helped her students explore what place means for them in conversation with localized, indigenous knowledge.

Debra’s students made sketches at a recently restored creek adjacent to her school’s property in Richmond, California. They drew and made natural dyes from the native plants that Debra knows intimately from her experience as a master gardener. I have had conversations with Debra about teaching at the lesson level, and also about her framework on differentiated learning and cultural wealth. I appreciate this, and it allows me to make the connection between Debra as an instructor and Debra as a gardener with a meadow in her garden. I see this lesson as a metaphor for her pedagogy. She nurtures students the way she encourages her native plants to grow— she listens deeply as a way of understanding the conditions that help them thrive and by knowing that necessary change often happens at the edges of the meadow, both ecologically and politically.

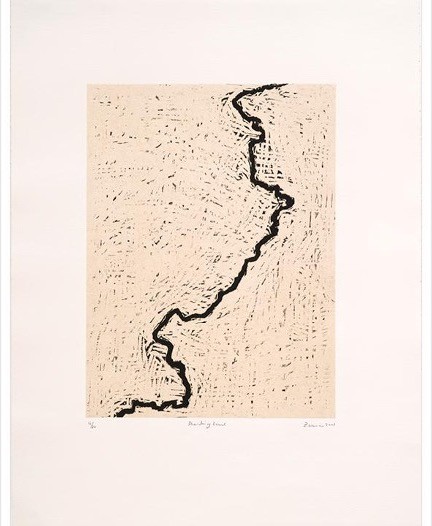

Zarina Hashmi, Dividing Line, 2001, woodcut print on handmade Indian paper, 65 × 51 cm.

As my unit unfolded in 2021-22, we moved through Zeke Peña and Tanya Aguiñga’s work and looked at Art21 featured artists like Minerva Cuevas, Brian Jungen, Postcommodity, and Graciela Iturbide (who illustrated a graphic novel). We also looked at Zarina Hashmi‘s cartographic prints about instability and migration. We talked about how Zarina’s prints reveal the harsh gouging and ‘excavation’ of the wood block itself, making us ‘feel’ the disruption of the Radcliffe line. And then we listened to art historian Aparna Kumar describe these violent marks as a kind of negative space left in the wake of erasures and retellings of events like the Partition and war.

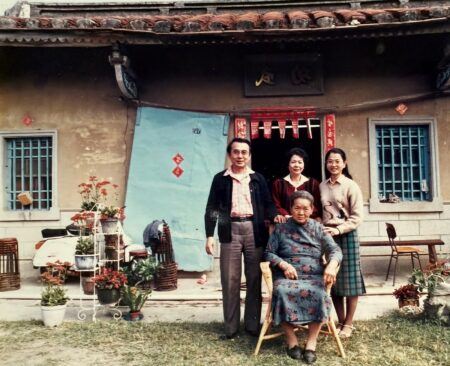

In my most recent iteration of this unit, we spent time with questions about the War in Ukraine: What does solidarity with oppressed people internationally look like? How do artists participate in advocacy? Students were inspired by artist Jenny Yurshansky, whose work draws on her personal experiences with inherited trauma and the displacement and aftermath of immigration. In response, students who felt comfortable shared their own family narratives of immigration, change, and resilience through collage, drawn images, and written narratives. These images were designed on a template so they could be folded into playful paper fortune-tellers, and we shared on the discussion board to reflect on the stories and connections among us.

Production still from “Art in the Twenty-First Century,” episode “London.” © Art21, Inc. 2020.

The theme spilled into questions about global toxicity. I introduced contemporary ikebana master Atsunobu Katagiri, projects like Don’t Follow the Wind, and works from other artists that participated in Japan’s regeneration and reconstruction following the triple disasters of 3.11 in Japan. I wanted us to see how borders cannot contain, among other things, our nuclear realities: we are linked and entangled through the extraction of uranium, radiation, nuclear waste, toxic/negative commons and toxic trades, with the greatest burdens borne by our most marginalized populations. It made sense to connect this content with Art21 artists LaToya Ruby Frazier, Trevor Paglen, and Mel Chin.

Over the span of these thematic modules, students scaffolded and charted their thinking through sketch notes, poems, posters, creative expression, and video recordings. They also drew concept maps revealing overlaps and nonlinear connections of places, histories, and issues. These mappings and other discussions demonstrated students’ increasingly complex understanding of how artists tell stories about places and that we too could participate in the storytelling and formation of community knowledge. Unraveling the intersections of the many ways we create meaning shows us that we can find our most urgent stories and participate in imagining a more resilient future together, through art.