Sarah Ceurvorst (she/her) is an artist, educator, and activist based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She believes that art can be a catalyst for positive social change and works to create that change within her communities. She has been a member of The Ellis School’s Visual Arts Department since 2015 and the Program Director for LEAP (Leadership, Excellence, Access Persistence) at Carnegie Mellon University since 2021. She previously worked with Contemporary Craft, Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, the Pittsburgh Office of Public Art, and Carnegie Mellon University’s SocialChange101 initiative. She also taught English language and visual art classes in Thailand as a Fulbright Scholar. She served as the board secretary of the Greater Pittsburgh Area Fulbright Association, a volunteer with the Son-Rise Program, a steering committee member of the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council’s Pittsburgh Emerging Arts Leaders and a member of the University of Pittsburgh’s PRIDE Teacher Cohort. She is a member of Art21 Educators, where she works with a global network of educators and artists using contemporary art to address contemporary issues.

Teaching with Contemporary Art

Unlearning with Contemporary Art

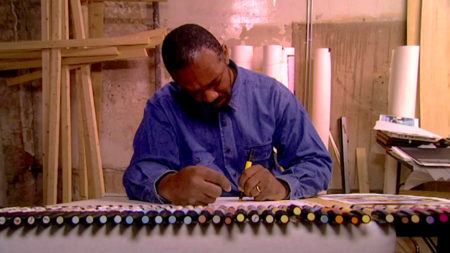

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 9 episode, “San Francisco Bay Area.” © Art21, Inc. 2018.

The classroom is far from the only place where students learn. Whether from picture books, YouTube advertisements, or conversations overheard in the grocery store, children constantly absorb informational patterns around them. This learning is not constrained by school hours and it does not take summers off, and unfortunately, it does not always give kids accurate or equitable information. Research has shown us that, at a young age, most children become saddled with biases — racism, sexism, and ableism — even if these concepts have not been explicitly instilled in them at home or school. These acquired prejudices are introduced to them through a wide variety of sources. For instance, a child may believe that only white men can be doctors if that’s what they’ve seen on television. Children continually learn prejudice and bigotry from the world. The art classroom is a space where students can begin to deliberately unlearn some of that bias. Through simple practices, such as showing images of artists’ faces and playing videos of their voices, the art classroom can become a space of radical change.

Countering these harmful messages involves sharing the perspectives of contemporary artists with our students. Engaging directly with the work and words of artists can effectively help students combat learned prejudices. Bringing contemporary artists’ voices into the classroom through videos frees me from needing to always be the expert. It means that I do not need to speak for someone else or pretend to know what their life is like. Rather than condensing or summarizing the words of a Black man in classroom discussions about race, I can let Nick Cave directly speak about how his soundsuits protect him from the dangers he faces in America. Instead of reinforcing the fallacy that disabled people can’t speak for themselves, I can allow the artists of Creative Growth Art Center to assert their views and to contribute to my class’s dialogue. In decentering my voice, I can show students that I am not the lone keeper of knowledge,and that artists’ insights about the world can push back against biased messaging they receive through cultural osmosis. Democratizing the educational experience by playing videos of artists’ voices helps students unlearn that power is centralized in my white, typically-abled, cisgender body. It enables students to learn from a diverse array of experiences and expertise.

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kameelah Janan Rasheed: The Edge of Legibility.” © Art21 Inc., 2021.

When I taught students about the Old Masters of painting, I never heard sentences like, “That looks like my sister!” When the faces of Jordan Casteel or Kameelah Janan Rasheed come onto the screen in my classes, the room lights up with comments like, “Her hair looks like mine!” and “She reminds me of my aunt!” The likenesses of Michaelangelo or Rembrandt did not allow most of my students to connect my curriculum to their own lives in a meaningful way. Conversely, introducing my students to a contemporary canon of artists gave kids who felt unseen a chance to recognize themselves within the spotlight of success.

By upholding contemporary artists as the heroes of a lesson, students get to see a diverse array of people being celebrated in an academic space. They unlearn what traditional museums have long taught us: that you need to be a “stale, pale, male” to make art worth studying. Showing the faces of artists who span gender identities, races, ethnicities, and abilities challenges the notion that only some people’s ideas are worth listening to. Highlighting images of contemporary women artists helps girls learn that their voices matter just as much as their male peers. Displaying images of contemporary Black and Brown artists helps children of color internalize that their excellence deserves to be recognized.

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Jordan Casteel Paints Her Community.” © Art21, Inc. 2017.

Rooting my educational practice in contemporary artists helps me to unlearn just as much as it helps my students. It has profoundly transformed what I thought an art classroom could be. In some of my own elementary school experiences, I learned that art in school had to focus on acquiescence and final product. Contemporary artists opened my mind to art education that mirrors contemporary artistic practices — one that values experimentation, process, and divergent thinking. As a result, my students have become more engaged, independent, and confident in the classroom. Previously, my students constantly sought external validation by asking me if what they were making was “right.” They asked this because they knew that what they were creating was coming from a predetermined picture in my head — there was a right and a wrong way to create. Now, with contemporary artistic practices and perspectives guiding us, I see students who are eager to express their unique perspectives and forge their own processes. They unlearned the idea that art needs to be uniform and come from their teacher’s brain instead of their own; and in turn, I unlearned the pressure to strive for perfectly drawn pictures coming out of my classroom. Instead, I was taught to base my practice as an educator on deep conversations, resilience, and problem-solving. Using contemporary artists in the classroom allows me to continuously unlearn how to guide artmaking in the classroom. It has liberated me from being the arbiter of my student’s artistic practice, and has allowed me to be their facilitator, advocate, and cheerleader.