Teaching with Contemporary Art

Stuck at Home

Example for students by Ty Talbot (child’s self-directed artwork)

During the long, odd, Zoom-filled first days of the pandemic’s arrival in Seattle, I thought about how the traditional art classroom is not always the most ideal place for making art, especially contemporary art. Students usually come to the art room and find traditional art-making tools and materials: paints, brushes, pencils, pens, paper, canvas, and clay. Surrounded by these, they easily assume that art can only be made with such things and that mastering a traditional art-making craft is the clearest path to becoming an artist. Many contemporary artists, however, learn to liberate themselves from such material and technical constraints and often find deep inspiration in powerfully non-traditional methods of making. Distance learning, in this context, seemed to open up new possibilities of thinking and making. Initially, I was truly excited at the prospect of teaching differently.

Teaching from my home, I found myself revisiting the examples of contemporary artists who work from or focus on their homes in their practices. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s documentation of not only her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, but also the house where she grew up is a perfect illustration of how an artist can draw deep inspiration by telling the stories of what goes on right under their nose. As she explains in the New York Close Up short film, LaToya Ruby Frazier Makes Moving Pictures, “Your environment impacts the body, and it shapes how you perceive yourself in the world.” The collaborative work of video and photography that she created with her mother and grandmother over a period of more than a decade is as honest, direct, and moving as anything you may find in contemporary art. It is, in many ways, a heartbreaking love letter to the complexities of home as well as a blistering rebuke of the racist forces that left Braddock a toxic remnant of capitalism run amok. Frazier’s work wasn’t created in a studio or an art classroom, in frenetic 45- to 70-minute bursts. Like so many works of contemporary art, it required time, space, collaboration, and deep introspection. It also required the context of home. When my students and I were in the classroom, I often talked about Frazier’s work as a touchstone for thinking about how to use different methods of art-making to advance social, environmental, and racial justice. Now that we were all at home, Frazier’s work offered another dimension of meaning for us.

Student photography by Abigail Marschell

Many other contemporary artists also work with home-inspired themes—from Carrie Mae Weems in her Kitchen Table Series and Do Ho Suh in his installation, Rubbing/Loving, to Lucas Blalock’s 99¢ Store Still Lifes and Mary Mattingly’s efforts to document every item in her possession. During the first days of the shelter-in-place period, I shared these artists with my students, explicitly pointing out the commonalities in our experiences and art-making possibilities. The constraint of working from home, for these artists and for my students, encouraged different ways of thinking, processing, and making. In the Extended Play short film for the Kitchen Table Series, Weems asks, “How do we begin to alter the domestic space? … How does that get changed?” For my students during the pandemic, home became many different things: studio space, refuge, constraint, trap. As their teacher, I longed for them to use art to create domestic spaces of liberation, solace, and joy. But, from a distance, it was challenging to tell how successful they were.

Once it became clear that we would not be returning for the remainder of the 2019–20 school year, we realized that, among other things, our celebratory end-of-year art show would also be cancelled. The show is many things to many audiences, but for me it is an opportunity for dialogue; this year, in particular, there was so much to talk about. I challenged my students to finish strong and still aim for an end-of-year show, but this one they would host in their kitchen, on the sidewalk outside their home, in the garage, or somewhere else that felt most appropriate to the work. Otherwise, their learning objectives were to pursue joy, feel proud of the work, and display it in a way that would be compelling, clever, and purposeful. I let them find their respective ways, encouraging their paths as they veered further from traditional approaches of drawing and painting.

Student photography by Ezra Kucur

One student started building a couch, and another documented important places from his childhood through photographs and Google maps; one student made a dress that featured disparate materials, text, and ephemera from her home. Other students used photography and made text-based artworks to explore what it felt like to be socially distanced during uncertain times. Some students, of course, stuck to the safety of traditional media, but without the context of the art classroom, their methods became more interior, personal, and self-directed. However, even when students truly excelled in this context, the dialogue about the art remained largely confined to their homes.

As the school year concluded, and especially in the wake of the protests over the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, the practice of distance learning also started to show enormous cracks. Reports of widening learning gaps, child abuse and neglect, and parental stress revealed not only the critical roles that schools and teachers play in our society but also the fundamental inequality and inadequacy of our social systems.

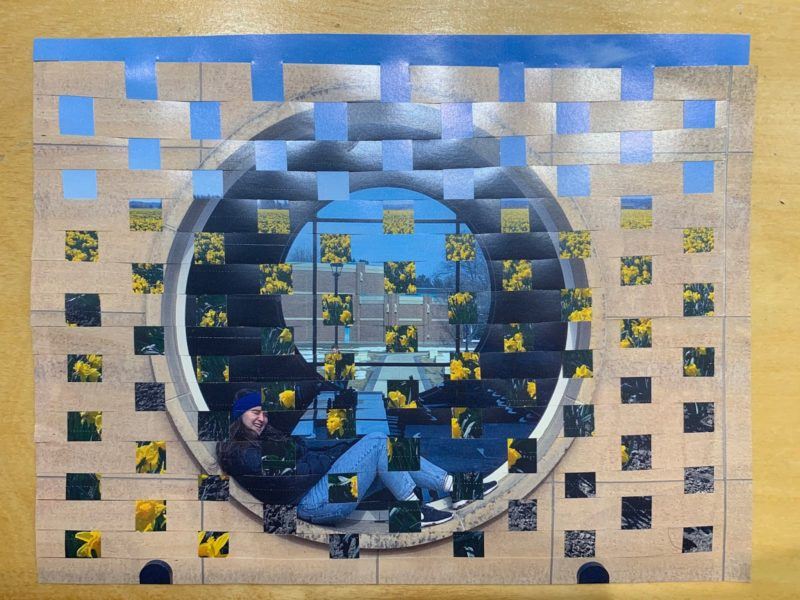

Student artwork by Ben Pepe

My classes concluded before large-scale protests and calls for justice broke out around the world. As summer dawned, I knew that many of my students were feeling terribly hurt and damaged. But there was little I could do to reach them in a meaningful way. While teaching from a distance liberated my students to make art with unconventional media, it also laid bare the critical importance of face-to-face dialogue, deep inquiry, and collaboration as foundations of contemporary art-making. As the Brazilian education philosopher Paolo Freire wrote in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “If the structure does not permit dialogue, the structure must be changed.”¹ While the structure of distance learning liberated my students and me from traditional methods of making, the Zoom call, the Schoology page, and the group email limited our means of connecting as humans in need of dialogue.

Student artwork by Rachael Selby

Thinking ahead to an uncertain future, I wrestle with deeply conflicted feelings about distance learning. On one hand, I relish the fact that teaching from home creates an opportunity for students to make artwork in non-traditional media and methods, and, indeed, some of my students flourished in this context. On the other hand, schools are often places of refuge from the turmoil of home—the “battle around the family,” as Weems puts it—and distance learning can only do so much for students caught in those battles. I felt that I did some of my most creative teaching this spring, spurred by the pandemic, but it often seemed to ring as the sound of one hand clapping. Distance learning forced me to think differently about how I teach, and teaching from home allowed me to see how I hope to grow, whenever I get back to my physical classroom, my home away from home.

¹ Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, thirtieth-anniversary edition (New York: Continuum, 2000).