Sonia D’Agnese has taught art to students ages 3-17 in the Maryland public school system since 2008. She is an Art21 Educator and National Board-Certified. She currently teaches Studio Art and Ceramics to middle schoolers. She takes a creative approach to art curriculum, balancing traditional artistic skill development with interdisciplinary learning experiences, focusing in particular on Social and Emotional Learning. She looks to contemporary art for innovative entry points to art-making that keep students engaged and confident that they, too, are artists. She has been an advocate for functional and supported inclusion in the arts in her district and continuously strives to bring her fellow educators together in dialogue with the goal of supporting and inspiring more meaningful and heart-felt learning environments for all.

Teaching with Contemporary Art

Interdependence and Access in a Middle School Art Classroom

Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

Artists can teach us what is important. Viewing the Art21 series, you realize the artists featured are concerned with so much more than making things. They are grappling with fundamental questions around what it is to be human in our time. The ideas they explore and the questions they ask drive their practice.

A 21st century art educator knows that to teach our students well we challenge them to think about art-making as more than as an isolated content area. Instead, we present art as a vehicle to understand the world we live in, growing their capacity to listen to other perspectives and form connections with one another. In other words, we teach them the important things.

I take the wisdom of artists and allow it to shape me and my teaching practice. I watch the Art21 series and read the educator guides looking for important ideas and questions to put to my students. Questions such as “What are your responsibilities to the community and people around you—things you are invested in doing regularly to show support?”, “How does someone transition from a stranger to a friend?”, and “How do we create a sense of belonging for others?”

In the film “Friends and Strangers,” multidisciplinary artist Cannupa Hanska Luger talks about the difficulty we all face with feeling a sense of belonging and in particular as an Indigenous person in North America. He talks about the myth of individualism and the importance of the indigenous culture of interdependence as a more sustainable way of being for our future. His work is largely collaborative and he describes it saying, “I always like to think of myself as an engineer and I talk about bridge-building as an artist. And the gap I try to span is the gap between all the different communities I interact with.”

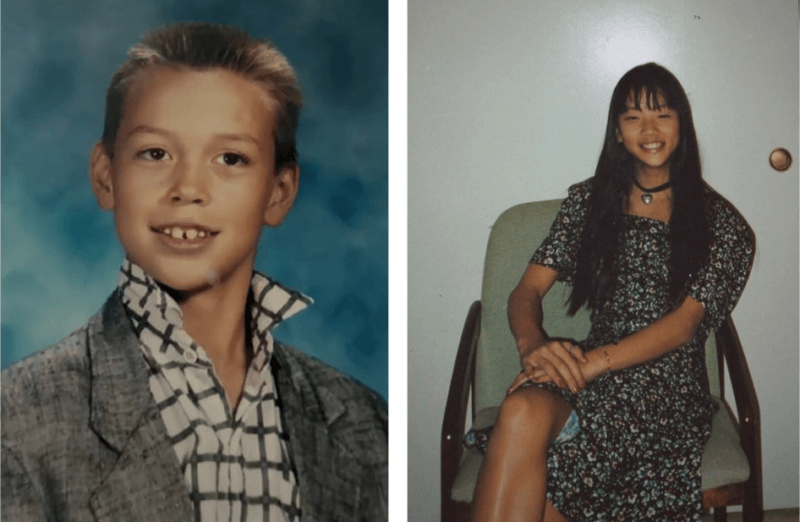

Artist Christine Sun Kim considers her right to be visible and understood and how society, institutions, and governments do or do not include and support all people. She describes a pivotal moment from her childhood in which she was denied access to art classes due to being Deaf.

Artists Cannupa Hanska Luger (left) and Christine Sun Kim (right) in their formative years. Production stills from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 11 episode, “Friends & Strangers.” © Art21, 2023.

These life experiences, ideas, and questions hit home and become the most important line of inquiry I could explore with my middle school students. How can we bridge gaps between diverse groups in the classroom? How can we go from being strangers to being friends? How can everyone access learning and feel a sense of belonging?

Like many art educators, I serve differently abled students in what is known as an inclusive education model. My school is among a few in the district that houses multiple Academic Support programs for a relatively large number of students with significant cognitive and physical disabilities. These students receive instruction in self-contained classrooms where they receive specific academic and physical support from trained educators for most of the day. They attend certain classes like art, where they can (working closely with a paraeducator) access the general education curriculum while their peers can appreciate learning with a wide range of neurodiverse people. Students in these two groups do not have many opportunities to get to know one another and even within the art classroom there was a noticeable divide. Students receiving academic support may be nonspeaking, which can present as an obstacle to communication for students who are unfamiliar with other forms of communication.

Students’ drawings of their classmates. Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

For general educators with limited experience or support, this instructional model can also feel challenging. I put a lot into modifying and adapting my art lessons, but struggled to be a bridge-builder between the supported and general education students. Art educators can sometimes be isolated in their school buildings, but for inclusion to be successful we need to honor our interdependence with others. So I began shifting my perspective and priorities. Opening dialogue and creating community with school leadership, special education resource teachers, and paraeducators was vital. Like Luger explains, no artist or person can do anything alone, so I reached out for help. I researched inclusive practices such as emphasizing connections and the importance of working collaboratively. Creating individual projects was less important than creating a capacity in students for collaboration and mutual understanding. Making community norms explicit eliminates students’ hesitation to initiate interactions. I incorporated more activities that required peer to peer interactions such as partner portrait drawing in the place of self-portrait drawing. Students interviewed one another, using a list of questions they could ask if they felt stuck. In one particular lesson, students had “line conversations,” responding to each other’s mark-making nonverbally.

Students having “line conversations.” Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

This past year my administration supported me in piloting a new art course in which students work exclusively in partnership with students in the self-contained special education programs. In planning this class, I incorporated Social Emotional and Social Justice standards. 7th and 8th grade general education students are responsible for co-designing the learning experience using the interests of the different members of the class, researching art forms and materials in order to develop art activities, which they then demonstrate to the whole group. For example, as the general education students learned more about their special education peers, they noticed some students’ love of music, and decided to create craft instruments to play. Students devised alternative art making tools to aid students with limited mobility or sight and together have explored a wide range of process-centered art making.

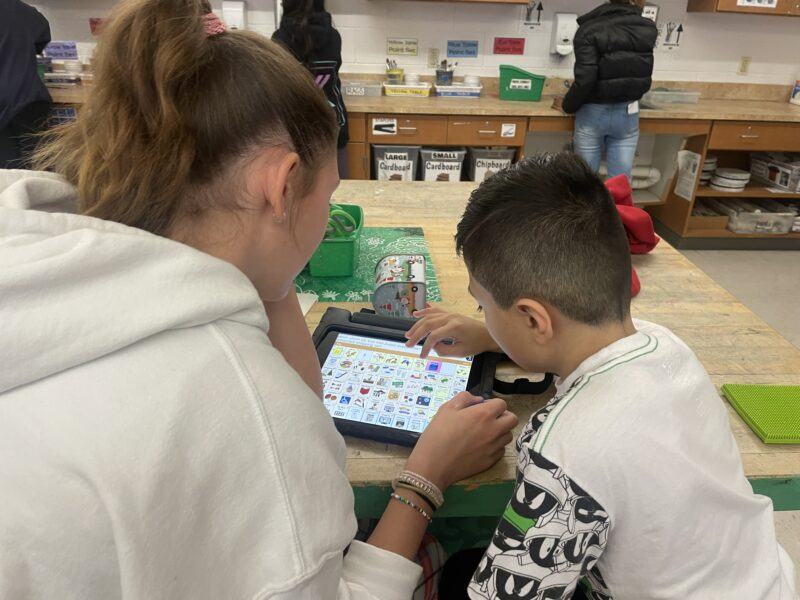

Two students use an Assistive Communication Device (AAC) to aid communication. Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

Students communicate using low tech visual symbol systems, Assistive Communication Devices (AAC), and often facial expressions and gestures. They laugh together regularly, but have also learned to regulate frustrations and to maintain patience and calm when some challenging behaviors arise. It is moving to see how readily and joyfully the students have bonded. The school as a whole benefits as the caring energy generated in this class ripples outward to the hallways. These efforts have increased all students’ visibility and genuine inclusion. They now all know each other by name. They say hello to each other at other times of day and walk hand in hand as they head back to their homerooms. By word of mouth, more students have enthusiastically signed up for the class for next year.

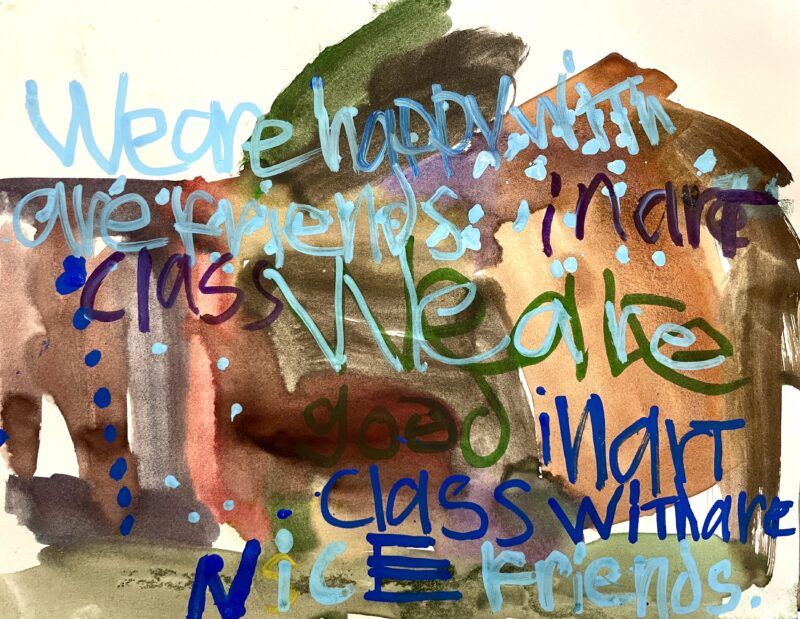

Student art piece that says “We are happy with our friends in art. We are good in art with our nice friends.” Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

Inspired by the artists of the world, we can find the impetus to overcome longstanding divides that were never inherent to the children, but rather to the limitations of the imagination, practices, and structures in place. Practices and structures can be rebuilt with the creativity and wisdom of artists. Contemporary artists are not only our inspiration for engaging in exciting new art-making practices; they can be our guides to exploring the most relevant and important questions of our time, in our own classrooms, helping us create a more compassionate humanity.