Murtaza Vali—What are some precedents from within your practice for The Knowledge Keepers (2024), your recent sculptural commission for the Huntington Avenue Entrance of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston?

Alan Michelson—Many of the ideas can be traced back to a commission I made for a permanent public artwork on a very problematic site: Richmond’s Capitol Square, where Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia State Capitol is located. Inside the rotunda stands French neoclassical sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon’s famous full-length statue of George Washington (1785-92), also commissioned by Jefferson and sculpted at Mount Vernon, Washington’s estate. The former capital of the Confederacy, Richmond’s famous Monument Avenue once featured sculptures celebrating Confederate heroes. Though removed in recent years, they were very much in place when I was working on that project.

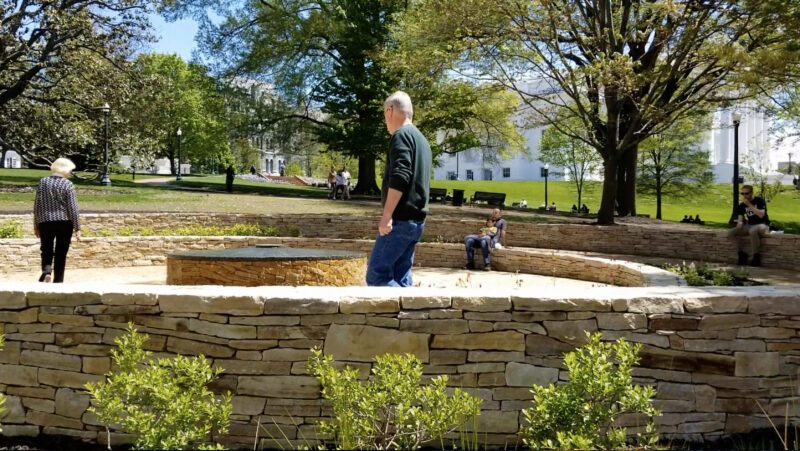

My intervention, Mantle (2018), is a different type of monument, an earthwork that reinscribes indigeneity onto that conflicted landscape. It was based on a gift from Chief Powhatan to King James that included an object called Powhatan’s Mantle (c.1600-38). The object consists of three deer skins sewn together and embellished with tiny snail shells. It features a human figure flanked by two four-legged animals in a field of thirty-four small roundels, which might have represented a map of the subtribes of the Powhatan Confederacy. The roundels are embroidered as spirals and, recalling Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and the significance of the spiral as a growth form in nature, I incised this form into the landscape.

What I find missing from much site-specific art, except in a very abstract and perhaps poetic way, is an acknowledgment of how the site has been shaped by human beings. This recognition renders any site historical, forcing us to reckon not just with its current state but with its pasts as well, for example, prior to colonization. Excavating and revealing these shifts—which index distinct attitudes toward the land—is what I am trying to do.

I remember touring Boston’s Freedom Trail at age nine and being blown away, not by the usual historical monuments, but by the subtle one that marks the site of the Boston Massacre of 1770, which set off the American Revolution. It is just a circle of cobblestones, a dozen feet in diameter, with a star engraved on the central one. No verticality, nothing vainglorious. It was electrifying, that sense of history and time trapped in a site, of the site as a silent witness to the past.

MV—And is The Knowledge Keepers the first time you have worked with the figure?

AM—My people come from the Six Nations Reserve, a diasporic reserve we were displaced to from our original homelands to the south. The first work I made using a human visage was Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer) (2018), for a show at the Woodland Cultural Center, in Brantford, Ontario, located near the reserve. It was about the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, a Revolutionary War event in which the American army, under orders from Washington, invaded Iroquoia to fight the four of our Six Nations that had sided with the British.

As I was researching, I realized how my own people were unaware of the history of this genocidal expedition and its horrific consequences. It was a scorched-earth campaign, designed to burn us out of our homes and villages, destroying acres of prosperous farmlands and orchards and herds of livestock. It was our Trail of Tears. I projected this history of invasion and dispossession onto a life-size replica bust of Washington by Houdon that I purchased from a museum store. The projection included historical maps of the territory prior to the Revolution, the evolution of the campaign against us, and its aftermath. Washington was always on the make, trying to build wealth and enhance social position by coveting and seizing Native lands.

The work’s title is the name used to refer to Washington by my people. He inherited it from a great-grandfather who, during a period of conflict between the Virginia tribes and the colonists, murdered five Susquehanna chiefs who had come to parley and was dubbed Hanödaga:yas or Town Destroyer. Washington proudly claimed this problematic inheritance, often adopting it in correspondence with Native peoples so as to appear formidable. Such titles tend to stick, and this one has become parlance within Haudenosaunee circles for the American presidency in general. I mounted the bust on an antique surveyor’s tripod—a reference to Washington’s apprenticeship as a land surveyor in lieu of college—transforming it into a monstrous chimera.

I recently reproduced that same bust in mirrored stainless steel for the re-opening of the Princeton University Art Museum. Exhibited alongside Charles Wilson Peale’s portrait of Washington (George Washington at the Battle of Princeton (1783-84)) and William Rush’s bust (c. 1817), it represents a dissonant perspective, stealthily occupying a form that has generally excluded and specifically erased us, appropriating some of its power. The bust sits atop a pedestal of carbonized hardwood, which is an abstract distillation of the destruction Washington wrought on my people and their lands. Set off against the deep, sooty black of the pedestal, the bust’s slick reflective surface distorts the icon and the space surrounding it, challenging and complicating the indoctrinated patriotism usually associated with Washington. And by visually reflecting the viewer, it questions and implicates: what does this icon mean to you? Do you see yourself in it? Does it reflect your histories, ethics, and ideals?

MV—What is the significance of the shiny surface in the case of The Knowledge Keepers?

AM—I wanted to distinguish The Knowledge Keepers from run-of-the-mill bronze sculpture while still maintaining a dialogue with that tradition. The platinum gilding I ended up using recalls the reverence that Eastern Woodland peoples have for shine and luster, and for substances that carry it, such as shells, copper, and crystals. Colonization brought silver, which immediately became a valued material and medium of exchange. It is also linked to exploitation, as many Native peoples colonized by the Spanish were forced to work in silver mines.

I initially thought to use silver, to harken back to this history, but then realized that it would tarnish quickly, especially outdoors. Platinum was a way to get the same look but is hardier and, as it turns out, has a fascinating history as well. Found in river banks in South America, Native populations there used it for ceremonial jewelry and other ornaments. And through its use in advanced electronics and spacecraft, platinum also indexes the future.

MV—Their reflective surfaces reminded me of Cannupa Hanska Luger’s Mirror Shield Project (2016), which he conceived of for protestors at Standing Rock, using reflection to protect against and resist the projections of the colonial gaze and the real violence it enables.

AM—The Knowledge Keepers are a retort to Cyrus Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit (1909), also installed in front of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. That tradition of heroic bronze statues tends to inflate and elevate. The Knowledge Keepers are intentionally life-sized. This human scale makes them relatable and somewhat vulnerable, countering some of the amplitude of the Dallin, which sits atop a tall plinth. The Knowledge Keepers also stand on plinths, but their physical elevation rebalances a history of denigration, of being looked down upon.

Dallin’s sculpture is very much a projection. The Lakota of that time would not have chosen to represent themselves that way. The war-bonneted mounted warrior is such a romanticized figure in American history, more of a hollow icon than a person. I wanted to counter this powerful stereotype that continues to relegate Native people to the past. Responding to this depiction of a generic and anonymous Plains Indian in defeat, I wanted to emphasize Native presence and agency by honoring living Native people indigenous to Massachusetts.

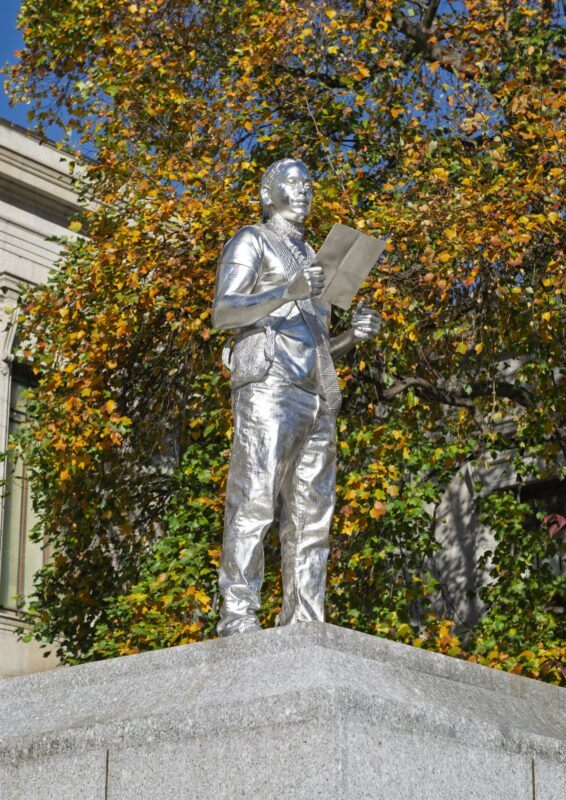

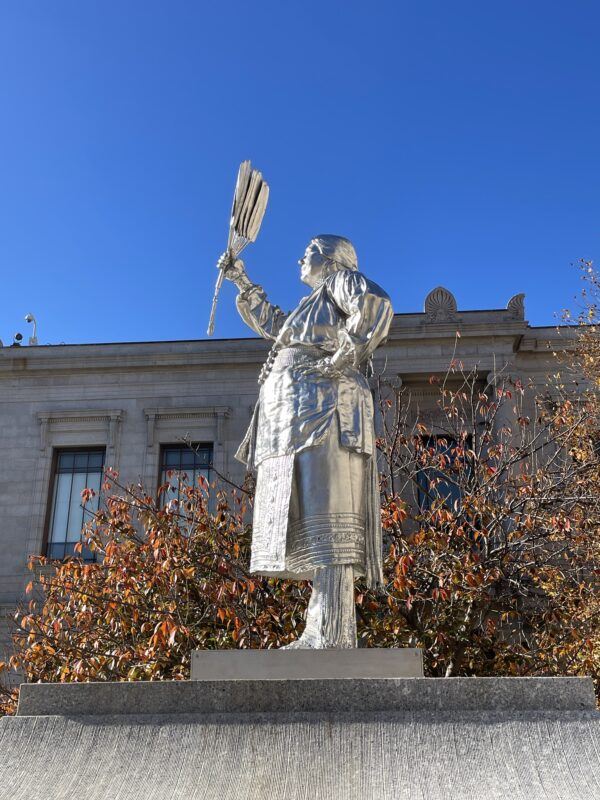

I feel very lucky that artist Julia Marden (Aquinnah Wampanoag) and activist Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines Jr. (Nipmuc) accepted my invitation to collaborate. Their poses and gestures, which embody their character and achievements, are key. Julia’s pose, with eagle feather fan raised, is a graceful and powerful honoring gesture frequently seen at Native events. And once I became familiar with Andre’s work as a teacher, I knew I wanted to portray him as an orator, sharing his knowledge, and based his pose on a photograph of him speaking, speech in hand. Julia’s regalia, most of which she made herself, speaks to the preservation of tradition into the future despite great odds. But I wanted to portray Andre in street gear, with some subtle Native touches, like his own wampum. Despite being elevated on plinths, neither appears overbearing; their gestures ensure they remain approachable.

MV—A dialectical tension between verticality and horizontality, between a critique of the former and an embrace of the latter, recurs in different forms and media across your oeuvre.

AM—As a species that learned to walk upright, verticality defines our world. Even the word “upright” has physical, philosophical, and moral associations. Conversely, flatness is often considered pejoratively, the idea of falling flat. But I have long been drawn to the horizontal. I love horizons. Though we might walk upright, we look ahead, towards the horizon, locating ourselves in relation to the sky above and the land beneath our feet. There is a sort of humility in horizontality, a proximity with the land. With Mantle, I wanted to shift people’s attention away from Richmond’s monuments—one-and-a-half times scaled, on horseback, on a pedestal—to the land, to its history, to it as a silent witness.

MV—In contrast to most monuments, Mantle, like Spiral Jetty or Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial (1982), is ambulatory, making you simultaneously aware of your embodiedness and your relationship to the land around you. One might say that this grounding shifts the rhetoric of the work from that of monument to memorial, from the heroic to the reflective, perhaps marking out a space for collective grief and remembrance. Do these ideas resonate with The Knowledge Keepers?

AM—I love the democracy of an open artwork, one that engages but does not prescribe the terms of that engagement. And the word “ambulatory” wonderfully describes so much of my practice, works that are intended to be moving experiences, hopefully on more than one level. And any extension in space is inevitably an extension in time. You can’t just look at Mantle and get it, you have to walk it to fully experience it.

Though The Knowledge Keepers’ platinum surface is not mirrored, it is still reflective. This reflectivity is a way of embodying time. It makes them receptive to their surroundings, to passing time, and shifting conditions. When you see them in good weather, under a clear blue sky, they’re blue, and in the fall, the changing colors of the surrounding trees make them appear red and yellow. One could even say that the surface symbolizes a type of Indigenous knowledge or wisdom, an intimacy with, openness to, and embeddedness in the land.

MV—How does The Knowledge Keepers complicate the idea you spoke of earlier, of the land as silent witness?

AM—They are, in some sense, the opposite. They speak volumes despite their silence. They are both witnesses and actors. They are sentinels, embodying the land and its histories through materials and practices, through the shells in their regalia, through their actions and ethics. For example, Andre is a steward of the land, caring for swamps and forests in Central Massachusetts. You may not hear what he is saying, but if you read up on him, you can imagine it: let us work together to preserve our traditions, to protect the environment, to resist the violence of colonialism and capitalism. Julia’s powerful stance counters the way Native people have long been represented as defeated and downtrodden. They undeniably embody agency and pride. They are community leaders, alive and present.