Teaching with Contemporary Art

Decay: Ecology of a Nurse Log

“Science and art are similar: in both subjects, it’s extremely important to ask questions, solve problems, and think about different possible outcomes. Scientists and artists can work together to gather the world’s attention to the environmental issues humans are causing that cannot be easily undone.”

—Holly, grade-9 science student

“My art asks you to think about both nature and sculpture not as objects but as processes.”

Why don’t they take away the dead logs?

As a science teacher, I am very fortunate that our school is situated next to a woodlot, an outdoor classroom just steps away from the blackboard, PowerPoint screens, and textbooks of our indoor classroom. On a visit to this woodland ecosystem, my grade-9 science students paused to consider a large dead tree that had been cut down and left by the pathway. One student asked why the city didn’t remove the decaying tree. It was dead, so why not get rid of it? This question prompted a new lesson.

What makes an ecosystem sustainable?

I love to get my science students to look at the natural world in an interdisciplinary way, a creative way. I want them to think beyond textbook illustrations and scientific diagrams and to be able to ask big questions about the world around them. Though the aforementioned student didn’t realize it at the time, his was one of those big questions, which opened up a discussion that would bring about another exploration of how the work of artists and scientists can converge and inform each other.

How can artists and scientists work together to better understand the natural world?

The Science: Our grade-9 study of ecology investigates the sustainability of ecosystems. We look at the ecological roles of different organisms—producers, consumers, decomposers, and scavengers—and consider the importance of each role in keeping an ecosystem balanced and healthy. And there’s nothing better than a dead log to show how everything in nature plays an important role.

Fallen and decaying trees can provide the nutrients and resources that germinating seeds and small seedlings need to grow, sometimes in greater abundance than the forest floor. Other small organisms also find shelter and food on and underneath these dead logs. Dead trees are the nurseries of the forest, thus they are called nurse logs.

The Art: Mark Dion explored the vital and intriguing role of a nurse log in his installation, Neukom Vivarium. For this work, which presented a reversal of my class’s expedition to the woodlot, Dion moved a dead tree indoors, to create an experiment in sustainability. I showed my class the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 segment, “Ecology,” in which Dion took a sixty-foot, fallen hemlock out of the forest and into a museum in the heart of Seattle. We considered how and why he enlists the help of scientists to create an artwork.

Some of the guiding questions included:

- What does Dion mean when he says, “That’s the excitement of this piece: Once it is finished, it is just started”?

- What will be needed to sustain this nurse log?

- What kinds of scientists were working on this project? What did they do?

- How do artists and scientists work together on this project?

- What do you think Mark Dion wants to learn with this experiment?

- What might the public who visit the Vivarium learn about ecology?

- How is the Vivarium an artwork? How is it a science experiment?

An interesting conversation ensued. Students disputed whether the log was an artwork. Some felt that Mark Dion is more of a scientist than an artist. Some felt that the work was more of a science experiment. Everyone agreed that the artwork was definitely science and that much could be learned from it.

Back to the woods

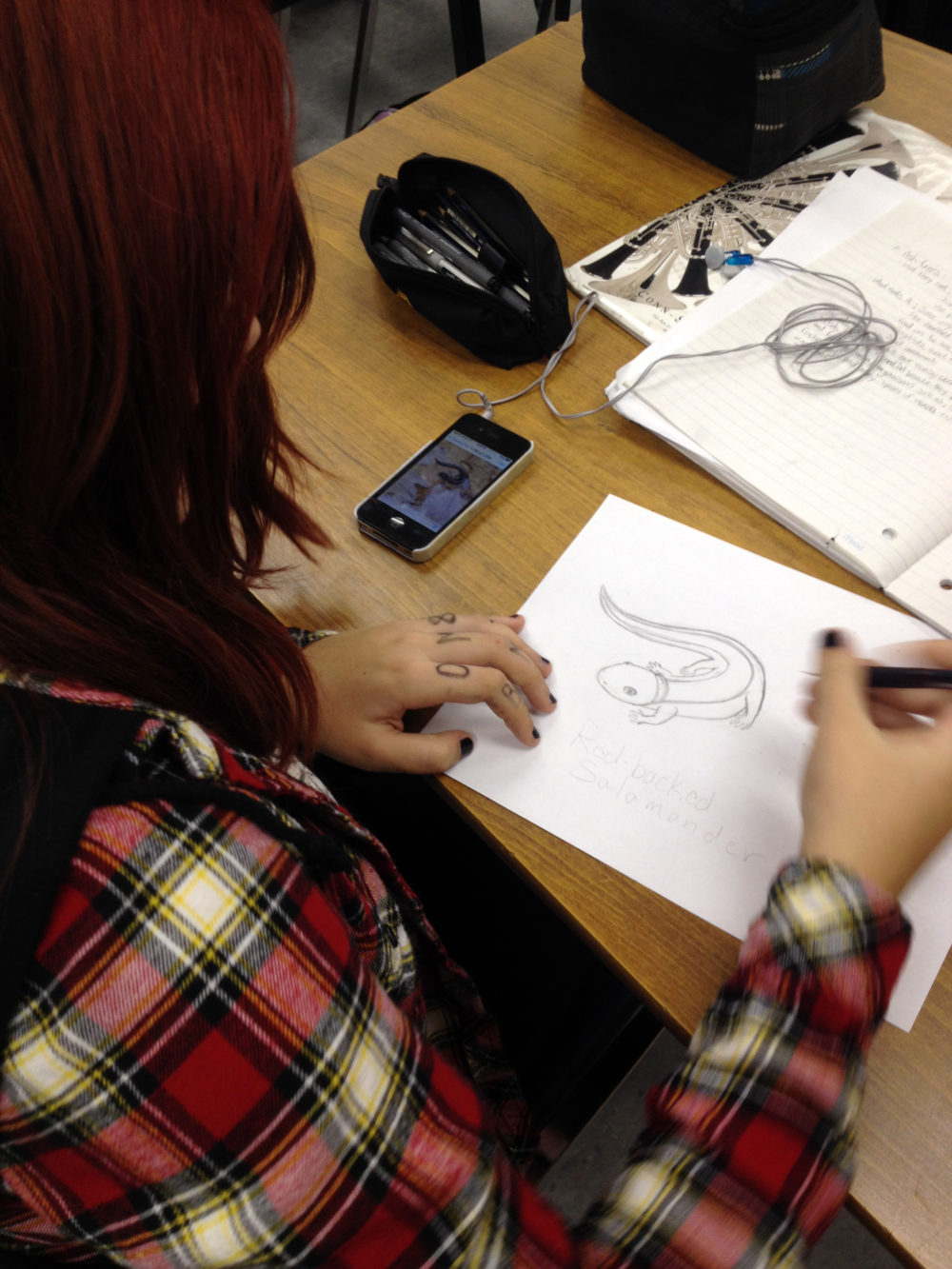

My class headed back into the woods to take a closer look at the nurse log. We peeked underneath it, finding sowbugs, worms, and salamanders. We examined small saplings growing from the top and shelf fungus and mushrooms clinging to the sides, breaking down the wood. We talked about the roles of decomposers, producers, and consumers that live in and around the log. We talked about balance in nature and the impact that we, as humans, can have on this balance. Our woods are home to an endangered species, the Jefferson Salamander, and though we did not find this species, we did unearth its cousin, a red-backed salamander. The students wondered why one salamander could be endangered while another still thrived under the log. What is required to sustain a healthy balance for all organisms?

Is Dion’s Vivarium a sustainable ecosystem?

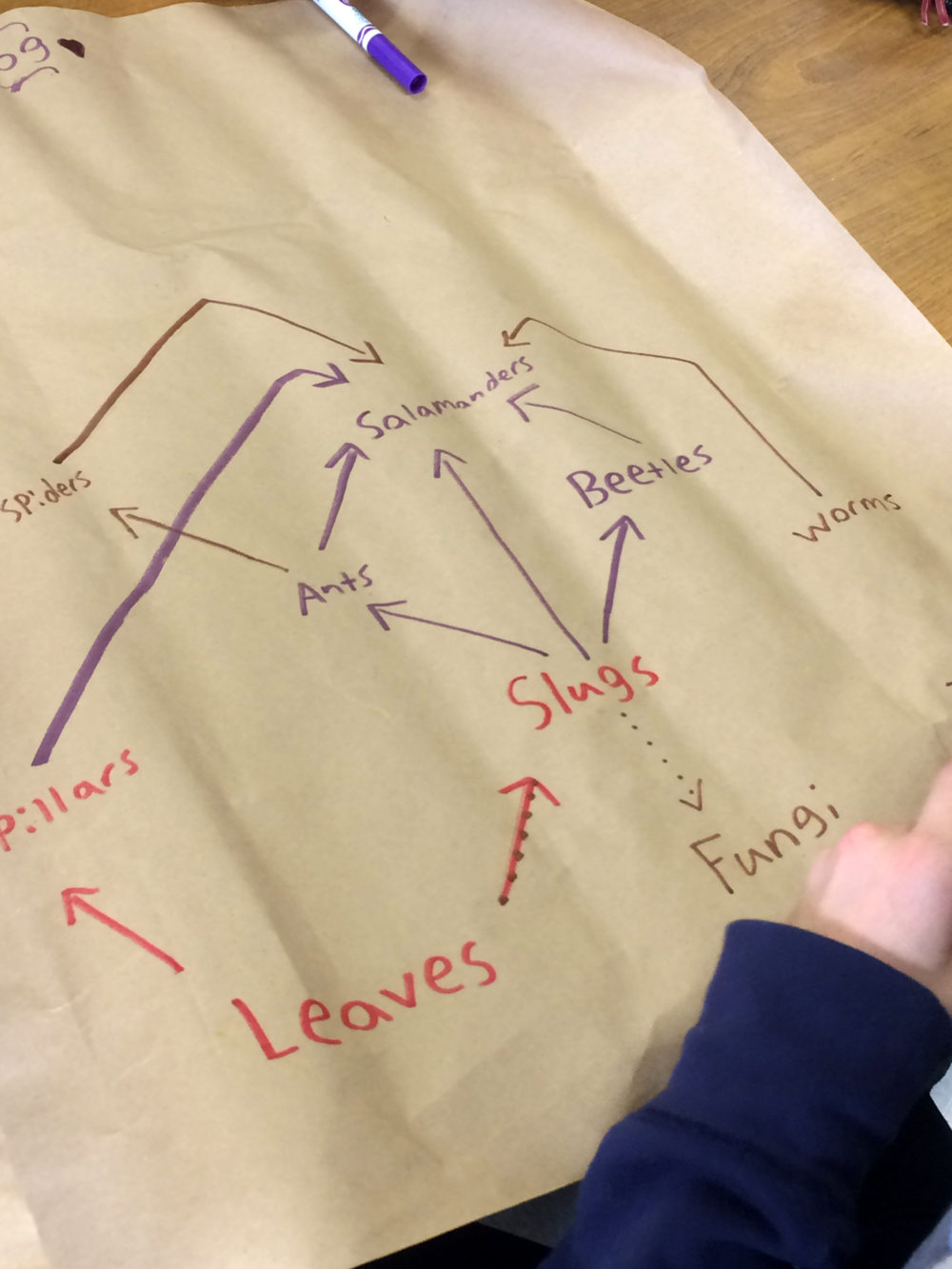

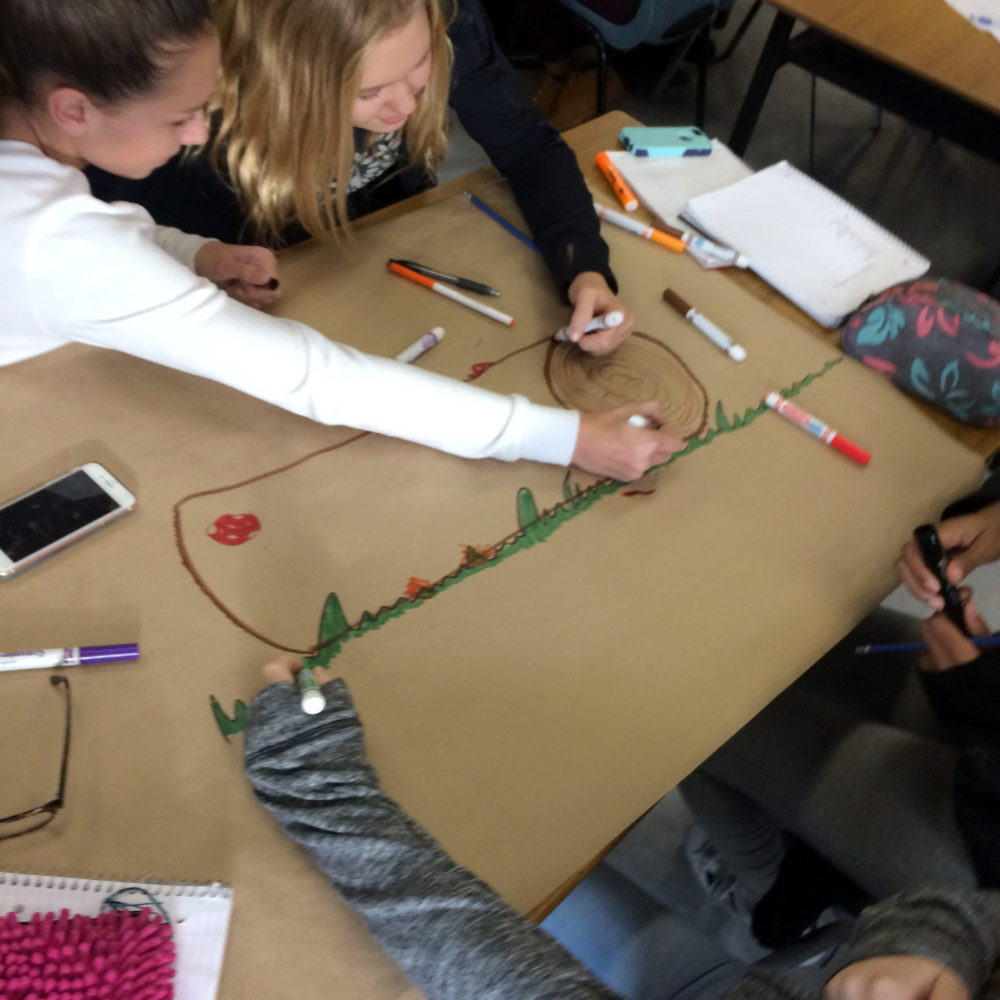

Back in the classroom, the students worked collaboratively to create large posters outlining all the components that Dion’s Vivarium would need in order to function as a sustainable ecosystem. They researched the biotic components: what organisms would live on the decaying hemlock tree? They drew food webs based on the organisms that would be found on a nurse log. They also considered the abiotic (nonliving) factors that would need to be in balance: temperature, water, sunlight. What did Dion have to do to maintain these factors in the Vivarium? How much would humans have to do, in place of what nature would have done in the forest? Is this process sustainable?

Science through a contemporary art lens

Mark Dion’s work opened a door to rich conversations and to a better understanding of what it means for an ecosystem to be sustainable. My students were challenged to think critically and to ask questions, not just about whether the Neukom Vivarium is an artwork or a scientific experiment but also about the positive and negative impacts that humans can have on ecosystems.

Our next step in the unit was to create an aquatic ecosystem in our classroom, which we would monitor over a month. Using large jars, students created mini aquariums called “eco-bottles,” each containing only a snail, a fish, and an aquatic plant and intended to be self-sustaining. Without human input, would it be a sustainable ecosystem?

As one class set up their eco-bottles, a student turned to me and asked, “Ms. Fitz, is this going to be an artwork?” And so began another lesson…

“Artists can also work with scientists to get across an important message about almost anything…The job of a contemporary artist involved in science is usually to convey a message in a meaningful way and help people—who might have a hard time understanding a long lecture with long words—to understand what is happening. And it really does help and make you see and feel things that you wouldn’t have felt before, and it takes you into the topic and makes it so real, and makes you really a part of it.”

—Thomas, grade-9 student

Art21 artists and videos that bring art and science together:

- David Brooks, “David Brooks Is In His Element,” New York Close Up, March 2013

- Mel Chin, “Revival Field” (text interview) and Mel Chin in “Consumption” (video)

- Matthew Ritchie, “Propositional Player” (text interview)

Learning Goals:

- Students will understand the biotic and abiotic components that work together to make an ecosystem sustainable.

- Students will connect the work of artists and the work of scientists, and the ways artists and scientists can work together and inform each other’s work.

- Students will explore the impacts—both positive and negative—that humans can have on natural ecosystems.

Resources:

- Art in the Twenty-First Century, Season 4 episode, “Ecology”

- Lesson summary, Google Slide Presentation

- Worksheet to accompany video on Mark Dion, in Art21 “Ecology” segment

- Eco-bottle project handouts [Handout 1, Handout 2]

All images courtesy of the author.