Interview

Expanding the Role of the Artist

Theaster Gates in Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century.

Theaster Gates shares what he sees are the possibilities for artists to go beyond the making of objects, to actively contribute to and better their communities.

ART21: Do you see artists as having another role outside the traditional role of “artist”?

GATES: Even mentioning that artists would be involved in things that are outside of our studios is quite controversial for other artists. And I’ve seen this conversation play itself out, that in fact we should not have to be called upon to patch the problems of struggling communities. We should not have to be the ones who take on the question of police brutality in our country or black male violence in our country. We should not have to be the ones thinking about unfair labor practices. But in fact there are artists who are willing to take up these causes. Artists who understand that sometimes the artistic affect is better than policy, it’s more complicatedly inclusive than the town hall meeting. There are these ways in which artists can wield the world and make really amazing things happen because they’re not just dependent upon the money that can be raised to generate a protest, [because] the protest is in the work.

So when I think about the work that Rick Lowe is doing in Houston or I think about Laurie Anderson being in conversation with this guy from Guantanamo Bay, that in this way artists are attempting to have real world things emerge. Raising issues that would not be raised in the same way on CNN or through a media network. And I think those moments where we could do much more than create an object of desire, that’s cool. Maybe even that it’s necessary. That at some point the object of desire, it does what it does and it does it where it does it. And I just think, whoa. Is there more for me to do in a day? And I think there is.

ART21: How do you see object- versus engagement-based art?

GATES: So if we were to accept that there are these possible two camps, one camp would be object-based practices and one would be engagement-based. I’m going to deal with this as a kind of dichotomy for the moment. Object-based practices are what we traditionally imagine as art. It’s a thing that you can look at on a wall. It’s a sculptural object that you can see in a museum. It’s a thing to be touched. This engagement-based stuff is a little bit more complicated. It’s often based in relationships. Sometimes it produces a set of things, but not always. Sometimes it only wants to produce an effect. It takes many forms. It could take any form that is sometimes object-based and [sometimes] not. But I think that both parts of those things live within my practice. I am a lover of sculpture and painting and drawing, and I spend a tremendous amount of my time thinking about that stuff and making art in that way. But I feel like whatever would be an engagement-based approach is simply a way of saying that people are also important to the work that I do. And that by engagement I am asking someone else to enter the territory of art with me in saying, you know can we do this together? Whether it’s the Black Monks of Mississippi making music with me—a temporary gospel choir and we’re all singing about Dave the slave potter with new music I’ve produced—or a set of Turkish plasterers who are helping me to conceive of new bodies of work, or the creation of a political party by Tania Bruguera. There are ways artists are [pursuing] these things outside of our studios that include other people. This is a moment where it feels like there is gross permission, both by the artists ourselves and within this creation of art history, that people are starting to do that.

Art just has so many colors and flavors and ways of presenting itself. And we’re calling out two ways, engagement- and object-based, but we would need a lot of words that would function as descriptors for [different] kinds of practices. And maybe the value of those words is that they help people focus themselves, like they see a thing happening and they can say, oh, that’s art, right. But I think that one of the things that has me very excited is that there are things I want to make for which people may not snap and have an ‘aha’ moment. They may miss it as art altogether. And I think that might be a kind of artistic future that I can invest in, that in fact you won’t know what you’re looking at. (LAUGHS)

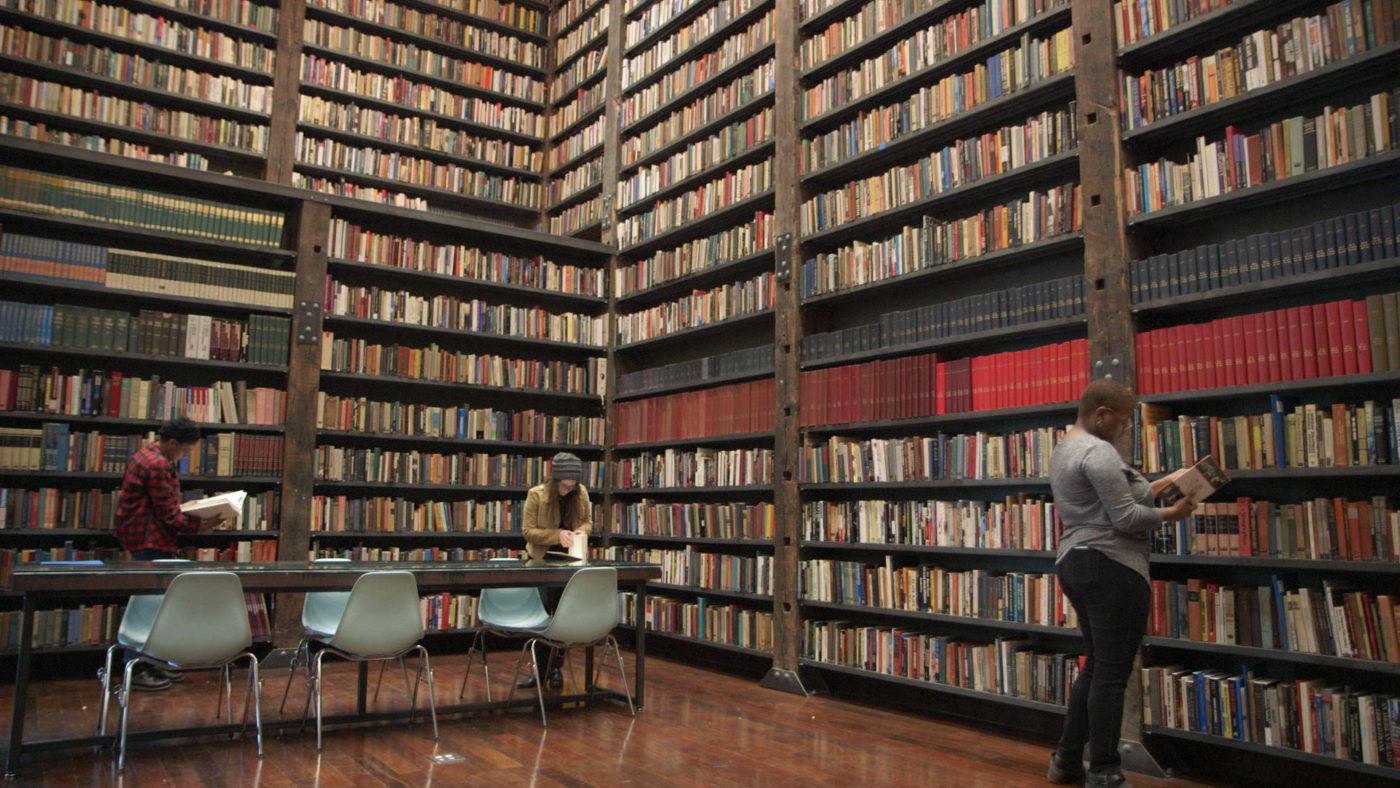

The Rebuild Foundation‘s Archive House and Listening House. Production still from Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

ART21: What relationship do you see between materials and discarded communities?

GATES: I know that the work is always acting as a stand-in for a more complicated set of questions. That is, what if I didn’t just have the gymnasium floors, is there a conversation that I should be having about the future of education for young black boys? For the 26,000 men and women who are detained in our jail system in Chicago, for the 100,000 men and women that are detained per year in that space? Is there a way that there’s some other kind of education opportunity that would act as a redeeming function? But I don’t know what that is yet. I don’t have jobs for the 10,000 men that might come out of jail this month. But man, what if I did?

And so I’m always thinking about that gym floor, and the gym floor is trying to answer an artistic imperative. But there’s this other thing that I want. I actually want a solution for the 10,000 brothers coming out of jail. Is the gym floor important? To say that education is important, these schools are closed, this thing is happening, these are challenges. But what advice can I give my friends in government? What are the advices they could give me that might inform the way that I use St. Lawrence Elementary School, this building that we acquired down the street? I’m still wrestling with the relationship between the symbolic work that ends up on a wall and the pragmatic work that kind of changes lives or creates new education options, or creates new employment pathways. All of that stuff feels like a good creative problem to solve. I’m actually excited about this idea that a work could at the same time be itself, be the demonstration of a thing, and be part of the solution of the problem that it’s referencing.

Production still from Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

ART21: How could it become the solution?

GATES: It becomes part of the economic opportunity that allows for the restoration of a building. It becomes the solution that allows for the hiring of a couple men or women. It becomes a reminder to others who don’t have to look at the ugliness of poor places. That there are poor places and that that starts to do its own work.

As I’m thinking about the objects that I want to put in the world, the people that I’m engaged with, I cannot think about the impact that we’re trying to have on the south side without thinking also about the fact that these things are luxury items that live in a market. That in the same way that my going to the university every day has value, my making these works of art has a value. And that value together, my incomes allows me to do this thing that feels bigger than the everyday work of development, or bigger than the everyday work of planning a new school. It feels like I’m participating in changing the mindset of how people imagine black spaces. And I don’t mind the bigness of it, and I don’t mind the investment. But I would be remiss if I didn’t say that part of what allows this work to happen is that there’s a set of objects that are made and those objects go out into a very hungry market that has an appetite for the objects that I make.

I love that artists are also important to our cities. That there’s a way in which maybe the solutions that we have for our cities are slightly different from traditional solutions, and the models that we use to get to a solution are slightly different.

Production still from Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

Production still from Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

ART21: How have you seen these kinds of solutions at work in Chicago?

GATES: If I really had to answer this question of can art and culture revitalize communities, I would want to say, no. I’d want to say no because it shouldn’t be the job of art and culture to deal with water problems and unemployment. Should art and culture be the thing that has the burden of changing communities? Probably not. Are there other things alongside art and culture that need to happen in order for a healthy community to emerge? Absolutely. Like art and culture may not be after-school tutoring. It may not be the healthcare center. But I think that when art and culture are present, when it’s doing its thing well, it becomes a kind of magnet for lots of different possibilities.

When art and culture are present, other kinds of things want to be present. Schools want to be better, neighbors want more for themselves, government is willing to do more to advance the built environment in those places. And I feel like I’m involved in that work. I’m involved both at the level of making art happen and then making culture evident. And sometimes making culture evident is simply giving a platform so that culture can do what it does.