Teaching with Contemporary Art

The Power of Juxtaposition

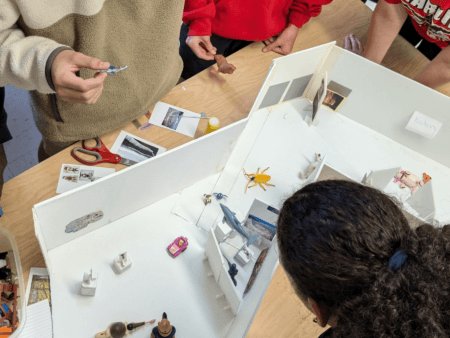

Fred Wilson visits with educators at the Art21 Educators Summer Institute, New York, 2018.

Art21 enthusiasts are familiar with the fact that contemporary artists often intertwine their art-making work with their roles as engaged citizens and social actors. Today, educators, students, artists, and art appreciators are questioning the role of artists; soft power is a fitting term to describe the subtle and nuanced ways in which artists influence the social and political sphere. Whether creating a platform for public dialogue out of chalk (like Allora & Calzadilla), questioning definitions of beauty (like Jessica Stockholder), or drawing attention to injustice (like Ai Weiwei), artists everywhere are transforming aesthetic practice into political practice. Much as soft power is nuanced, artists are mindful of complexities, especially regarding histories, storytelling, materiality, and relationships.

How can we make the intricacies of soft power utilized by artists accessible to students? Identifying and studying the tactics that artists employ to pose a question or assert a message can reveal their works’ influence on society. Juxtaposition is one tool used by contemporary artists to persuade viewers or elaborate on an idea; it demands that artists become conscious organizers of content. For example, Fred Wilson is a master of combining similar yet different culturally charged objects in a way that evokes connections between local and global economies and challenges assumptions about history, race, and culture. He encourages viewers to reconsider social and historical narratives by reframing typical perspectives of objects and cultural symbols. While such a description of Wilson’s work is accurate, it is difficult for most students and adults to grasp. In a museum visit or in the classroom, we can use Wilson’s artworks to illuminate the soft power that artists leverage through juxtaposition.

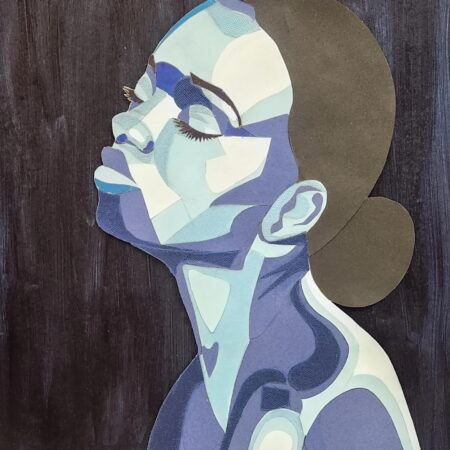

Fred Wilson. The Way the Moon’s in Love with the Dark, 2017. Installation view at Denver Art Museum. Purchased with funds from Vicki and Kent Logan; Suzanne Farver and Clint Van Zee; Sharon and Lanny Martin; Craig Ponzio; Ellen and Morris Susman; Devon Dikeou and Fernando Troya; Baryn, Daniel and Jonathan Futa; Andrea and William Hankinson; Amy Harmon; Arlene and Barry Hirschfeld; Lu and Chris Law; Amanda J. Precourt; Judy and Ken Robins; Annalee and Wagner Schorr; Judith Zee Steinberg and Paul Hoenmans; Tina Walls; and Margaret and Glen Wood, 2017.207. © Fred Wilson. Photo: Erica Richard.

As a museum educator, I am particularly excited about the Denver Art Museum’s recent acquisition of Fred Wilson’s chandelier artwork, The Way The Moon’s In Love With The Dark (2017). This artwork has the potential to spark critical conversations that reveal the careful decision-making that leads an artist to the deliverance of a powerful message. By unpacking some of the complexities in this artwork, students may gain a stronger understanding of how to use juxtaposition for persuasion as well as to test their spheres of influence. If I were to lead a guided experience concerning the use of juxtaposition, it would begin with close observation. With the intention of directing students toward analyzing the juxtapositions in this work, I have prepared questions and supporting resources that can help to probe the issues and guide the conversation:

- Have you seen chandeliers outside the museum? Where have you seen them? When you see one, what message does it usually send?

- Have you ever seen a chandelier in this color? Why do you think the artist made that color decision?

- What do you notice about the light fixtures?

- What contradictions or opposites do you notice?

My intention is that, after discussing answers to these prompts, the group acknowledges some shared understandings: that chandeliers are symbols of status or wealth; that chandeliers are usually made of clear glass and gold or light-colored metal, but this one is not; that it looks both delicate and heavy; that it is illuminated brightly yet is created from dark metal and black glass; and that it features two distinctly different types of fixtures, some angling upward and others hanging downward.

I feel it is necessary to provide supplemental visual resources to help students understand the histories and significance of the two types of chandeliers embodied within this work. Rather than immediately telling students the cultures or locations from which the chandeliers originate, I share images of different types of chandeliers and their cultural connections, in order that the students might notice that this art shares the most similarities with Ottoman and Venetian chandeliers. Once we have identified the types of chandeliers, we can dig deeper, into the metaphorical relationship between the two locations represented, Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Venice, and ask: Why might these chandeliers be combined in this work? Visual geographic connections can help to clarify the relationship between the Ottoman Empire and Venice; for example, I might show maps that mark trade between the two regions and across the globe during the time of the Ottoman Empire and a depiction of the areas conquered by the Ottomans. After investigating this contextual information, students can better understand how Fred Wilson uses juxtaposition to convey a complex message about local and global economies and to challenge assumptions about history.

How does Wilson challenge history to consider Blackness and African people? How does he ask the viewer to engage in a dialogue that addresses displacement, visibility, and identity? In order to reveal this aspect of Wilson’s work, I would mention to students that the title of this piece is a quote from the work of Alexander Pushkin, known as the quintessential Russian writer, whose great-grandfather was African and is believed to have been stolen or bought by the Ottomans before he becomes part of the imperial household in Moscow and a general in the Russian army. Pushkin wrote many poems and authored works that reflected pride in his African heritage.¹ I would ask students: What do you think Fred Wilson was implying when he chose this title? Are there clues that support your answer?

Attributes of identity and globalization are not only interwoven in this artwork but also can be seen throughout the museum. After wrapping up this discussion of Wilson’s work, I would ask students: Where do you feel you are reflected, in the histories represented and shared in museums? How do you see these objects interconnected throughout cultures and across time? Where are you seeing a mixing of cultures? To continue the exploration of concepts posed by Fred Wilson, students can create artworks that use juxtapositions to expose complex issues over matters about which they are passionate.

Juxtaposition is only one of many methods through which contemporary artists employ soft power, and it can be difficult to explain to students. By guiding students to uncover hidden meanings in artworks, we may help them to not only understand the messages in individual artworks but also expand their ability to identify juxtaposition in other artworks and develop their skills as engaged artists and citizens.

¹ Robert Coles, “Pushkin’s Black Consciousness,” CLA Journal 43, no. 1 (1999): 54–72. Accessed January 26, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/44324993.