Teaching with Contemporary Art

Teaching Love in Times of Unprecedented Instability

Production still from the Art21 “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 6 episode, “Change,” 2012. © Art21, Inc. 2012.

Life as an educator during the COVID-19 pandemic has been an emotional journey. I remember having a little sob when we found out we’d be closing for 2 weeks in March 2020, and then bursting into tears when we found out we wouldn’t be returning later that spring at all. I cried when I found out we’d be starting 2021 virtually. I cried again when I found out we’d be fully back in person in August 2021.

Each of these announcements struck a chord. I was almost always in full agreement with the decisions made, yet I never experienced a sense of relief once I finally heard the decrees I’d been hoping for; I just felt sad. Every time. Filled up with grief. Then bursting with it.

And then, it passes. And then, we get back to work.

Every time we make these shifts, I try to adjust my teaching objectives to the reality of what my students now need and what the new context demands of me. When my school district returned to the classroom in fall 2021 after a full year of virtual learning, I drafted a list of priorities. Many of these addressed the lessons missed from my high school photography curriculum the previous year—material-based content, like providing a darkroom experience and getting DSLR cameras in their hands, were top of the list. I also emphasized some thematic content, including Big Questions around Time, History, Storytelling, and Spirituality that we didn’t get around to last year. But as I thought about my students and me sitting together, face-to-face, in the same room, another thing came to mind. I added the word Love to my list and I knew I was ready to stop brainstorming.

Martin Puryear. Ladder for Booker T. Washington, detail, 1996. Installation view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Time,” 2003. Photo © Art21, Inc. 2003.

I want to suggest that everyone’s priority this year should be teaching Love—with a capital L. If that sounds a little corny, let me frame it differently. For a year, our worlds shrank. To varying degrees, many of our students lost their communities, or never had a chance to make them in the first place. They had fewer interactions with peers and adults than ever before, and many spent the year with classmates whom they never met, spoke to, or even saw. Because it seemed likely that the Delta variant might send us back to virtual after opening in-person this past fall, I felt like I had a potentially short window of time to offer students the sense of community they had missed the year before. I knew as soon as we returned to the classroom, it wasn’t going to be about diving into the technologies and techniques that previously dominated the first quarter of my photography classes. If I was going to be “flexible” and prepare myself for an inevitable “pivot” to virtual or hybrid (or some other new instructional expectation), my priority had to be the collective us. It had to be about laying the foundation for an artistic and educational community built on mutual care, or love.

Many teachers can probably relate to feeling like we barely got to know our students during virtual learning, especially in districts that couldn’t require students to turn their cameras on. I couldn’t bear the thought of returning to those black boxes on the screen in dark rooms, miles apart, without ever learning each other’s faces and names.

LaToya Ruby Frazier. Image of Frazier and her mother. Production still from the New York Close Up, LaToya Ruby Frazier Makes Moving Pictures. © Art21, Inc. 2012.

So, we learned each other’s faces and names. We played the name game over and over again. We talked about what it means to call someone by their chosen name, and that knowing someone’s name should be the very least that we can do to build a community here, to demonstrate we care that another person exists. I assured them that no matter how this year went, at least 25 people would know who they are, recognize their face, and be able to say their name. I quizzed them every day for a month. If they missed even one classmates’ name, they got a zero, but they were allowed to retake as many times as they needed. I wanted them to understand that knowing someone’s name is no small gesture. It matters greatly, and should be assessed as such.

Convincing a classroom full of teenagers that learning each other’s names is a form of love is a tough sell, so I don’t lead with the L-word. I’m building toward it by showing examples of art that’s absolutely brimming with love. Contemporary artists like Jordan Casteel, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Do Ho Suh are incredible sources for showing the complexity of the word and how it can so closely parallel community care. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s intimate portraits with her family inspire photo assignments of “self portraiture with others,” and her activism around economic and healthcare inequality demonstrate art-making that is deeply rooted in justice, tenderness, and protection. Frazier’s love is relatable and tragic, modern and relentless; it’s easy to be drawn into her work as if it’s a family album up on the shelf in our own homes.

Jordan Casteel in her Brooklyn studio, 2017. Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Jordan Casteel Paints Her Community.” © Art21, Inc. 2013.

We look at Jordan Casteel’s interactions with strangers while scouting and photographing, and later, her time spent alone meticulously painting her subjects, all as being acts of care in their own right. In her New York Up Close “Jordan Casteel Stays In The Moment,” her subjects attend the art opening with grins plastered to their faces. One subject, Quentin, looks up joyfully at his portrait and can’t stop blushing. Louie, another subject, frankly states about Casteel, “I love her.” He warmly recounts their interaction as a milestone in his life, that Casteel “dropped down [into his life] and did something nice.” These interactions—these moments of touching another’s existence—are overflowing with warmth, generosity, and sweetness. They are loving moments. How can we generate loving moments like these in our own portraiture of others?

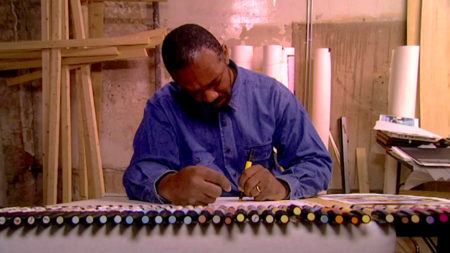

Do Ho Suh at work on Rubbing/Loving in the New York apartment where he lived and worked for eighteen years. Production still from the series Art21 Exclusive. © Art21, Inc. 2016. Cinematography: Ian Forster.

Far beyond the genre of portraiture, artists like Do Ho Suh painstakingly craft love letters to the spaces around them. In “Rubbing/Loving”, we see Suh’s entire apartment covered in white paper and colored pencil. Suh speaks of the loving quality of his mark-making as he renders his home on the walls, knobs, and moldings around him. As we hear Suh talk about the accumulated energy in the space, and the importance of this home to himself, his family, and his artistic career, we think about beloved spaces in our own lives. The homes, rooms, and environments that we’ve cared for, and if we’re lucky, the spaces that have also cared for us. Showing an artist who extends love beyond the romantic—in fact, beyond the human—bursts open the idea of love for students.

Still, it is the relationship Suh has with his landlord, a man who told him, “You’re welcome to do whatever you want to do in this house,” that brings me back to the core of my intended pedagogy of love. It’s the relationship between the two men that moves me (and, if you watch the video, will probably move you too). I want to be a teacher whose students know that they are welcome to do whatever they want to do in this house (read: classroom). I want them to feel seen and supported and loved by me. And more importantly, I want them to feel empowered and unashamed to extend that same capital-L Love to the people around them: family, friends, classmates, strangers. I want them to think of photographing as an act of love, portraits and landscapes alike. But I also want them to feel this way about talking, brainstorming, participating, and supporting, to see collaboration and creation as loving tasks. Everything from listening and sharing, to mask-wearing and greeting someone by name are acts of love, small but significant.

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

From my perspective, all good artists work with ideas of love. Love lives somewhere in their work or their practice; tapping into it helps us understand their artistic process and how to build our own. If you’re a teacher who is struggling to connect to this idea in your own curriculum, try using the artists you’re already familiar with teaching, and think about where love lives in their work. It might be easier than it seems to reframe your favorite illustrators, sculptors, and filmmakers as lovers: of their subjects, of their communities, of their spaces; of light, of color, of sound.

With my final breath here, I’d like to now suggest flipping this whole paradigm upside down. So much good art is based on ideas of love, yes, but more universally, all love is art. Yes, some of us have our artistic-practice side hustles. Yes, we value our summer-break studio time (if we’re lucky enough to have it.) But I hope you know that your art can also be the love you practice daily in the classroom. Teaching is my art practice. And it is the relationships I’m building, the connections I’m enabling, and the love I’m facilitating—whether we call it that or not—that I’m most proud of this year.

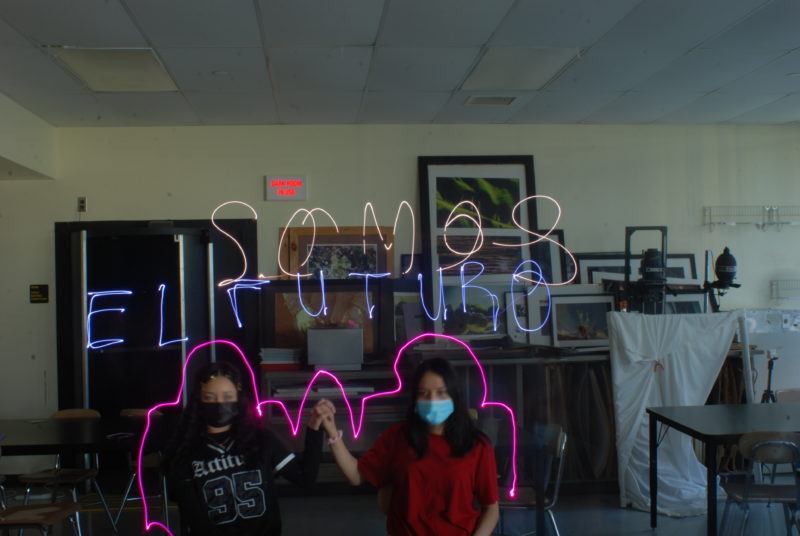

Photo by students in Ariana Mygatt’s Advanced Photo Studio class.

Of course, I didn’t invent this idea of teaching-as-care. Theorists like Paolo Freire and bell hooks have enumerated the ways in which a pedagogy of love can support both teacher and student. Friere writes, “I am more and more convinced that true revolutionaries must perceive the revolution, because of its creative and liberating nature, as an act of love.” Later, “If I do not love the world—if I do not love life—if I do not love—I cannot enter into dialogue.”

I’m not only suggesting we teach with love this year, I also beg that you teach how to love. January’s wave of the Omicron variant sent many classrooms back online, and many of us teachers into a downward spiral. Things are a mess. I don’t know if this is going to dig us out of our current global crises, but teaching to love is our best shot at getting the next generation involved in the changes, or revolutions, our society badly needs. In that light, I want to suggest that there’s a kind of necessity to approaching art and education as acts of love and care, even an urgency. It’s not too late to re-evaluate our priorities as educators. Try teaching love.