Interview

Portraiture & Representation

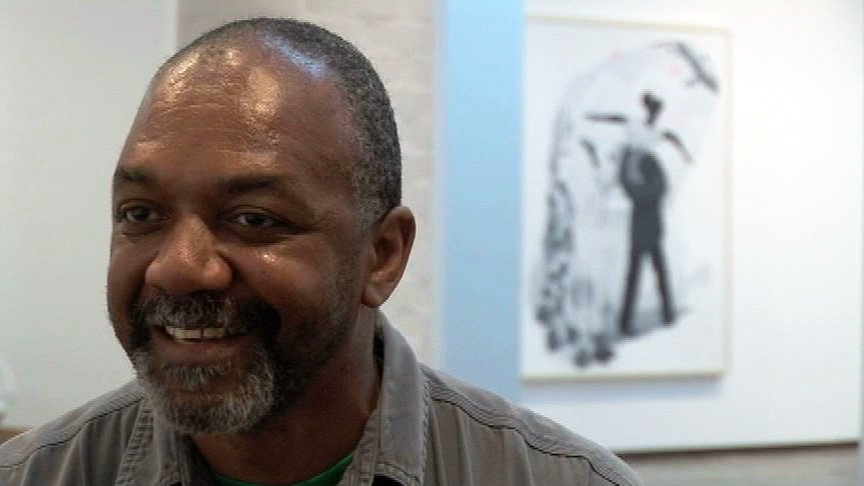

Kerry James Marshall at his Black Romantic exhibition, at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, 2008. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive series episode, "Kerry James Marshall: Being an Artist." © Art21 Inc., 2008.

Kerry James Marshall discusses the complexities of representational work, and how he sees his portraits existing outside of time.

ART21: You’ve said before that when you were young you knew you wanted to be an artist with a capital “A.” Do you see your recent portraits of painters as being related to a mythic or romantic conception of what being an artist is and is supposed to mean?

MARSHALL: Well…it’s the idea of the artist. And it’s the idea of the artist and what the artist looks like or what the artist represents. You could say that those paintings are a kind of mythic image of the painter. But part of what that work is also attempting to do is to address some of the challenges that this whole notion of Black Arts faces.

There’s this question surrounding representational work, which is the area in which Black Arts or that kind of work seems trapped in the minds of a lot of people. And the question concerns the idea that in order for the artist to become truly aesthetic, and be an individual artist as opposed to somebody attached to a group, then the work has to become abstract, which means you have to jettison the representational imagery for some other approach to an idea that doesn’t bear the burden of representation that the black figure tends to carry.

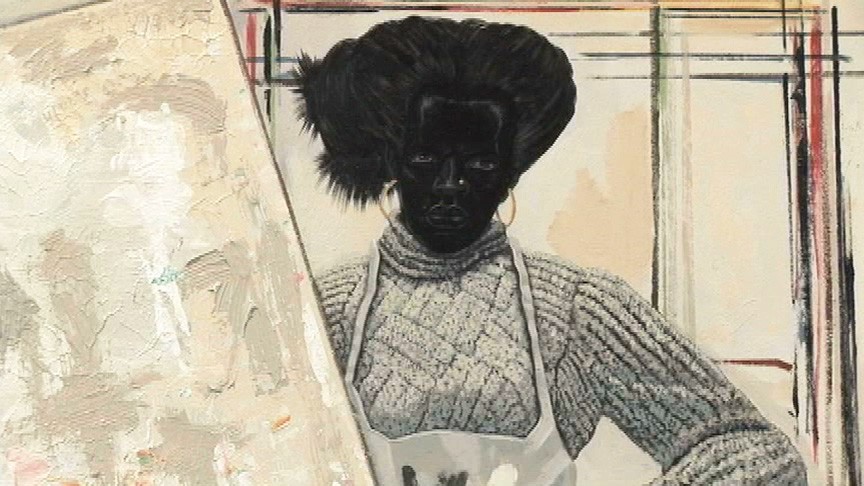

Kerry James Marshall. Installation view of Black Romantic at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, 2008. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive series episode, “Kerry James Marshall: Being an Artist.” © Art21 Inc., 2008.

And so the figures in these pictures are represented in a space where they are sort of between abstraction and representation. The palette each figure is holding represents a way in which abstraction is incidental. The palette exists as a kind of an abstract painting. The figure stands behind the palette as a kind of a representational image. And then on the wall behind the figure is the aftermath of the painting process, in which you work on the wall and at the edges of the canvas you end up with this sort of linear abstraction as a residue. So now there’s two different ways in which this kind of abstraction occurs. In both instances it occurs as a part of a process of making work, and it occurs as a part of a process of making representational work as well as a process of making abstract work. So you can be incidentally abstract—and that doesn’t make it less attractive or less profound—or you can be intentionally abstract. And then the figure itself is a stylized figure, so it’s another kind of an abstraction, even though it’s a representational image.

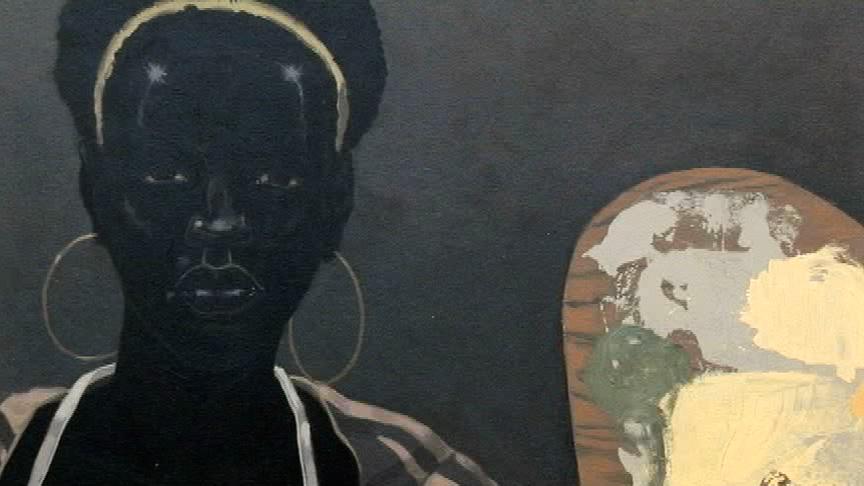

Kerry James Marshall. Untitled, detail, 2008. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive series episode, “Kerry James Marshall: Being an Artist.” © Art21 Inc., 2008.

ART21: Do you think of these as portraits of figures at a particular time and place? Are these pictures set in the past, or are these figures that would exist only today?

MARSHALL: They are outside of time I think. I mean there’s nothing in the pictures that locates them at any particular moment in history per se. They exist completely outside of time because I think this question of representation is not an issue that’s peculiar to this particular moment. This question has been asked by black artists ever since black people have tried to break into the marketplace and tried to be represented institutionally in the United States. It’s always been a question.

One of the claims that was made in the introduction to the Freestyle (2001) show at The Studio Museum in Harlem was that here are a group of 28 African-American artists who are adamant about not being called African-American artists. This idea of post-blackness. Well again, what does that really mean? Those questions have to be asked. And I think with these recent paintings, on some level I’m trying to ask “For whom is the representation a problem?” is a part of the question. When you ask the question about not being called an African-American artist, “Who are you asking it of?” is a question that has to be asked as well. The problematic is not in the artists themselves or what you call them, but it’s in the perception of somebody who you believe needs to change their perception in order for you to be seen correctly, or seen the way you would like to be seen.

Kerry James Marshall. Untitled, detail, 2008. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive series episode, “Kerry James Marshall: Being an Artist.” © Art21 Inc., 2008.

ART21: This problem of not being seen how you would want to be seen—or how you want you work to be perceived—are you ever discouraged? Do you ever find it depressing?

MARSHALL: The thing is, it’s only depressing if you don’t understand the dynamics of the situation in which you’re operating. If you somehow think that people are not supposed to think of you the way they think of you—then you have a problem. But if you see that as a part of the way in which human beings engage with each other in general, and that the activity we’re engaged in is not some kind of altruistic activity where everything is “I’m okay and you’re okay…” It’s not that kind of world. Everybody in the world is in competition with everybody else in the world. And you do whatever you have to do in order to gain some kind of an advantage in this competitive engagement.

One of the reasons why a negative value has been assigned to people who have color has to do with this competitive relationship that human beings have with each other. For the last five or six hundred years, we know that white people have been in the ascendancy, have been in control. This dominant group of Europeans and their descendants exert a force in the world, and everybody else who is not part of the group has a problem because of their relationship to the exercise of power that Europeans have been able to project. Now, if you didn’t somehow feel powerless and defenseless in this situation where there’s this gross imbalance of power, then you wouldn’t have a problem with what anybody called you.

This interview was originally published on the Art21 Magazine in 2008.