Interview

“Mine Site”

Artist Josephine Halvorson painting Tregardock (2011) in Tregardock, England (July 7, 2011). Photograph courtesy of Josephine Halvorson.

Josephine Halvorson shares the on-location California-spanning saga behind her 2011 painting Mine Site, and just as significantly, the painting she wasn’t able to make at that location.

ART21: What did we leave out in our film “Close Encounters with Josephine Halvorson“?

HALVORSON: In the video I speak about choosing objects to paint: I am trying to have a meaningful exchange with something out in the world, where the painting is the medium between us. But sometimes I choose a site to paint because I simply want to be in that environment. And I think as New Yorkers we tend to idealize the idea of landscape anyway. Openness itself is appealing. Often my decision will be based on weather, light, or something as prosaic as being near a toilet. Or I’ll just be stubborn and want to do a painting because I have my materials on me, even if I don’t have much inclination. Mostly those paintings don’t work out, but I do tend to have a good time. I find I make my best work when I’m neither a tourist, nor at home.

Artist Josephine Halvorson painting Steam Donkey Valve (2011) in Jackson State Forest, outside Willits, California (March 14, 2011). Photograph courtesy of Josephine Halvorson.

ART21: What places do you find yourself making these kinds of works?

HALVORSON: For years I’ve been going to coastal northern California to paint and visit friends. I went out there about a year and a half ago, in the spring of 2011. I’d taken some time off from teaching and knew I had a chunk of time to paint. But my excitement was dampened by an immense amount of rain. And I enjoy painting in the rain. I love the rain. But it was the kind of rain you couldn’t even drive in; it came down so constantly and so hard. And this was also right around the time of the Japanese tsunami. I painted Steam Donkey Valve (which was in my show What Looks Back at Sikkema Jenkins & Co.) on the day after the tsunami, in Jackson State Forest in Mendocino County. It was of a valve component of a larger machine–called a steam donkey–which hauled redwoods out of the forest. I encountered it only because I was rerouted due to road closures from the coastal flooding.

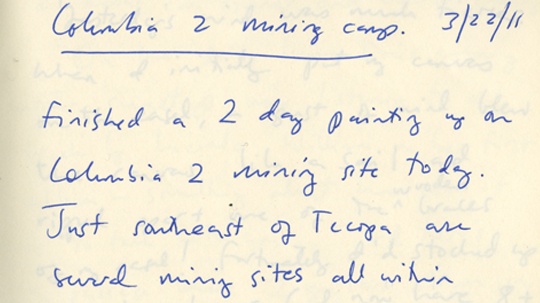

Entry from artist Josephine Halvorson’s personal log. Courtesy of Josephine Halvorson.

I finished this painting by putting up a plastic shelter over my set-up. But in the next couple of days the rain became more incessant and refused to stop! Because I desperately wanted to paint I ended up driving to the only place on the weather map where it was clear: Death Valley. I drove, I guess it must have been 12 hours, until I found this tiny town, Tecopa, right on the California/Nevada border about two hours west of Las Vegas. I had about a week remaining at this point, and was really surprised by how I responded to this area. I loved it there and had a feeling it would be good for my work.

Tecopa, it turned out, was a defunct mining town. I sniffed out the old mining camps which were south of town up on a mountain. No one’s spending the money to mine the hills anymore, even though you can see the streaks of the ore that shoot through the mountains. So there are very few jobs. It’s very bleak economically. And there’s no money for any kind of historical preservation. I made a painting up at one of these mining sites, and at one point looked down at my feet and I was standing on bullet casings, a can opener and similar remnants. People had just discarded stuff that might be in a museum if the site were in a different part of the country. This was such a vibrant place for mining and for the American West and it’s just been completely forgotten about, put on hold, ignored.

Artist Josephine Halvorson’s painting-in-progress Mine Site (2011) outside Tecopa, California (March 21, 2011.) Photograph courtesy of Josephine Halvorson.

ART21: How does that history find its way into your paintings?

HALVORSON: These are my notes about painting at Columbia 2 Mining Camp: “I finished a two-day painting up on Columbia 2 mining site today. Just southeast of Tecopa are several mining sites all within eyesight of each other. Talc depositories are also visible, as are so many peaks of mountains. Every inch of horizon is filled with hills and mountains, layered against each other, changing colors. The sun was strong and despite the sun block I felt tired, fried and sunburned. And then yesterday’s wind was much fiercer. I initially put my canvas on the easel and I guess the wind blew it over like a sail and ripped apart the wooden brace of my easel. So I was able to put the canvas inside the car, which is how I ended up doing the painting.” And this painting made it into the Sikkema Jenkins show. I called it Mine Site.

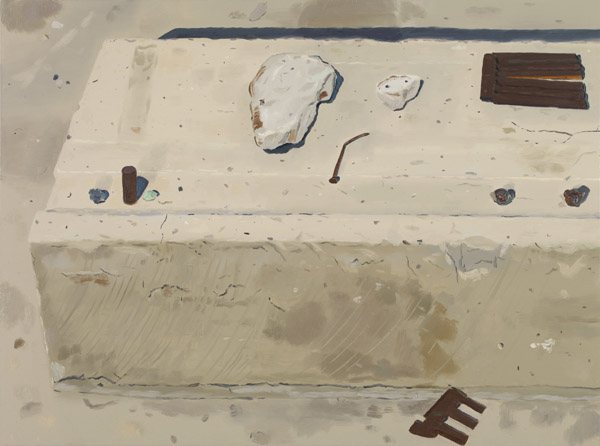

Josephine Halvorson. Mine Site, 2011. Oil on linen; 29 × 39 inches. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

ART21: Did you set up the scene at all for Mine Site, or does your painting depict how you found the site when you arrived?

HALVORSON: Well the interesting thing is Mine Site looks exactly like a still life, as does the actual mining site itself—strewn pieces of metal, residual components of machines scattered around concrete foundations. I went back and forth between calling this painting Desert Still Life and Mine Site. But no, I didn’t place any of these things here, they were there. They were found. But it looks like I put them there, it looks like a still life. And I liked that. I also liked thinking about how they might have gotten there. They were too heavy and awkward to have blown there. So someone must have put them there. But who, and why?

But Mine Site was not the painting I originally wanted to make. My intention was to paint this large machine, a diesel compressor, which probably provided power to operate the mining equipment. The first painting I’d started was thwarted when the easel was blown over. The wooden legs broke when it hit the ground. I’d replaced the problems of rain with those of wind. Instead I made Mine Site by half-erecting my easel in the back of my car, and reversing as close to the site as I could.

Diesel compressor at Columbia 2 Mining Camp outside Tecopa, California. Photograph courtesy of Josephine Halvorson.

ART21: Has this experience affected or inspired any other work?

HALVORSON: So what ended up happening was six months later I went back to Death Valley to paint the compressor. I had to wait until October, when the summer’s heat dissipated. But when I returned with all my painting equipment and conviction for this object, it had disappeared! After what could have been seventy years of being there, it was gone. And this was probably a whole ton’s worth of steel. I’m pretty sure someone stole it to make money from the scrap, which is understandable in the context of that economy. But I couldn’t believe it because I’d come all the way back out to Death Valley. I’d flown into Las Vegas and rented a car and made my way to Tecopa, then drove eight miles south of town and a mile up into the mountains where I risked puncturing my tires… It was heartbreaking that it didn’t work out. I guess you win some, and you lose some.

Columbia 2 Mining Camp outside Tecopa, California. Photograph courtesy of Josephine Halvorson.

The compressor was a great machine. It had been pushed over onto its side, thousands of dried maggots beneath it. It had a long face with a cylindrical “nose” that resembled Pinocchio’s. And on its rusted side someone had spray-painted the word, “Shame,” S-h-a-m-e. I hadn’t realized what that really meant until I returned six months later and it was no longer there. To me it was such a shame that it was gone and I had missed my opportunity to paint it. So in a way the word “Shame” anticipated my own disappointment. I thought I should have known it was going to disappear because of the word. Also because the “S” was slightly larger it looked like it was the machine’s name. And I kept thinking about that 1950’s Western, Shane, when the boy continually calls out, “Shane, where are you? Shane, come back!” And as I was driving up the rocky track up to the mining site, I thought just for a moment that it might not be there, like a premonition. And when I saw it wasn’t there I cried, and kept hearing my own voice calling out, “Shame where are you?” It was just so sad and I felt like I had let it down, like it was dying up there and I didn’t return in time. And I let myself down too. It was difficult.

I remember calling my father the next day and telling him what had happened. He suggested that the machine might have killed or hurt someone. These mines really are harrowing. You look right down a 45-degree tunnel of darkness into the earth. And these are huge machines without much safety protocol. So I could almost believe that. I hadn’t thought of that scenario until he mentioned it. And then I thought, maybe this machine does have blood on its hands, that there was some reason why I wasn’t meant to paint it afterall.