Interview

Resisting Dichotomies & Compressing Complexity

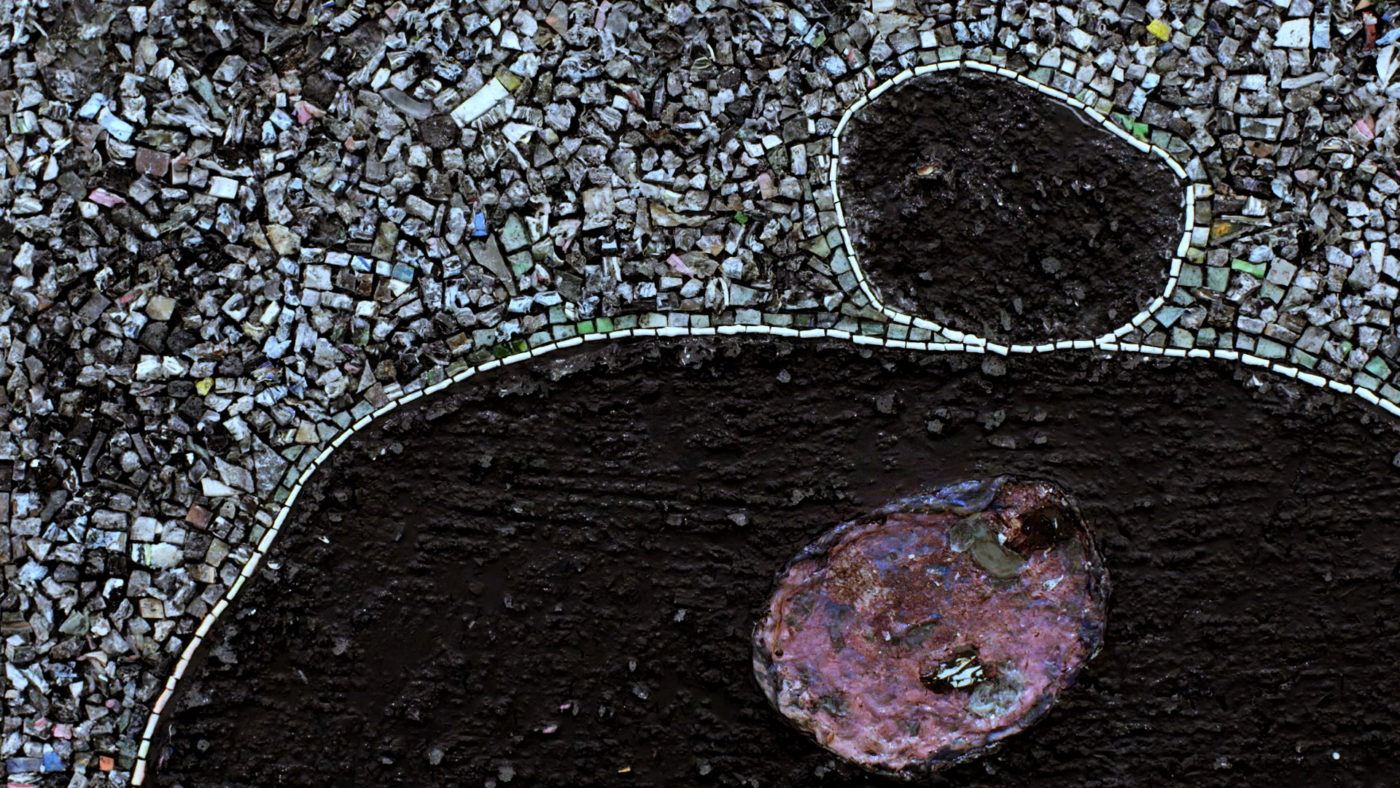

Detail of Jack Whitten's Black Monolith X, Birth of Muhammad Ali, 2016. Installation view: Hauser & Wirth. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, Jack Whitten: An Artist's Life. © Art21, Inc. 2018.

Interviewed in his Queens, New York studio in October 2017, Jack Whitten reflects on his childhood, the inequality he faced as a Black artist, and the necessity of fighting simplistic dichotomies.

ART21: What was your childhood like?

WHITTEN: I grew up in Bessemer, Alabama. I was born in 1939, at the height of the Jim Crow era, and I grew up in an environment that was very separate from White people. It was described as “separate but equal,” but in truth it was separate but never equal. The buses had signs: “White” on the front and “Colored” on the back. You couldn’t go into the restaurants. You could walk through the park in Bessemer but couldn’t sit down. I grew up under severe conditions, what I call American apartheid.

ART21: Why did you go to Tuskegee University? What did you study there?

WHITTEN: The school offered me a work scholarship, and I accepted it. I was a pre-medical student and an Air Force ROTC cadet. The idea was for me to be a doctor and a pilot in the U.S. Air Force, which, for someone coming out of the Black community, was a noble thing. But it was always in the back of my mind that I was an artist; I wanted to make art. I didn’t have a good understanding of what that meant. In retrospect, being in pre-med still informs what I’m doing in painting today. I was great with botany, zoology, and biology. Those were my favorite subjects, and I spent hours in the lab.

Tuskegee University was also the home of Dr. George Washington Carver, a scientist who did research on peanuts. But Dr. Carver was also a painter; he made his own pigments and painted small landscapes and still lifes. They are still there, at the school. Since I was doing janitorial work, more than once I had to clean Dr. Carver’s laboratory, which is intact, just the way he left it. So that had a big influence on my thinking. I knew about Dr. Carver before going to college because at that time, in Black schools, the instructors made sure that the students knew about notable Black people, those who had succeeded in different fields: medicine, entertainment, sports, writing.

Photographs in Jack Whitten’s studio, Queens NY, 2017. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, Jack Whitten: An Artist’s Life. © Art21, Inc. 2018.

ART21: After you came to New York in the early 1960s and started working as an artist, did you find that there were certain expectations of you, as a Black artist?

WHITTEN: Well, of course. Any time anybody deals with stereotypes, expectations go along with them, whether political, religious, or sexual. Being a Black artist, I faced expectations based on stereotypes: “You’re supposed to do this,” “You can’t do that.” But that’s bullshit.

Unfortunately, so many people are still stuck in that line of thought—what’s happening politically now, in America and in Europe—and it’s painful. Those old-fashioned stereotypes and severe dichotomies just erode the spirit, which is what we are witnessing today.

ART21: How are you countering that in the studio?

WHITTEN: I think of the paintings as an antidote to evil. My position is: I accept life as being difficult. Coming out of the South, I’ve seen some horrible shit. I don’t even talk about it. But I have a purpose; I have an agenda. I accept the fact that it’s difficult, but I’m not going to make it harder.

ART21: Your work is now collected by large institutions. Why do you think this is happening at this moment?

WHITTEN: It’s been hard for all of us Black abstract painters to get our work shown. It’s not just me. There are other people out there: Sam Gilliam, Bill Williams, [Melvin] Edwards. We went through long dry spells when nobody was interested. It’s been difficult for all of us. So finally we are getting more attention, like with the show in London at the Tate Modern [Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power]. That kind of thing is starting to make the difference. The main thing is that we are still intact; we’re still working. To say that you’re still working after more than fifty-some-odd years, and you’ve got your health, is kind of hip.

Jack Whitten at work in his studio, Queens NY, 2017. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, Jack Whitten: An Artist’s Life. © Art21, Inc. 2018.

ART21: With your upcoming shows in Baltimore and at The Met, some of that institutional attention is directed at your lesser-known sculptures. How are the ideas in your sculptures different from the ideas in your paintings?

WHITTEN: The sculptures began as what I call a research into identity. Instinctually I knew there was something in African sculpture that I had to learn. And after reading a lot of books and visiting museums, I wasn’t getting all the information I wanted. That’s why I started carving wood, as an investigation into African sculpture.

ART21: And where did your interest in mosaics come from?

WHITTEN: I have lived in Greece, on the island of Crete, since 1969, and I’ve traveled a lot in the Mediterranean area. Visiting sites of ancient mosaics in Europe and in Egypt, connected with African art, early Greek Cycladic art, Minoan art—all of it has influenced me.

ART21: How do you begin processing all these different influences?

WHITTEN: The key word is compression. These complexities are compressed, and that allows me to go directly to the subject. I read a lot of science; particle physics and astrophysics excite me. The ancient people had animist beliefs: they claimed that all matter had a life force. Studying particle physics and the workings of quantum mechanics tells us that all the aspects of matter can be broken down into these little bits, and they’re not static. I think something within that [idea of a life force is] what we need today, in terms of a worldview.

Jack Whitten selects acrylic tesserae for a work in progress. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, Jack Whitten: An Artist’s Life. © Art21, Inc. 2018.

ART21: How does this interest in science influence your art?

WHITTEN: Artists are not scientists. I mention science because that’s what excites me. Artists need something to fire up their imaginations, and different artists have different things. My excitement is what’s happening in science because I believe that art should reflect the period in which it’s made. It’s increasingly obvious to me that it’s evolution. As a painter, I think of painting as being organic. Therefore, painting evolves. It evolves like other organic structures.

Another thing I like about quantum mechanics is that the distinction between what is organic and inorganic breaks down. I love that, not only in its physical sense but also from a philosophical point of view. Racially, you’re Black or you’re White. Or sexually, you’re this or you’re that. I prefer a more fluid situation. [Instead of the terms this/that] I use neither/nor. It has more rhythm to it. In the [social] environments we have today, the spirit does not have a chance to flourish. People are exhausted, so they fall back on old-fashioned ideas because it’s easy. It doesn’t require any thought. It doesn’t require any effort.

ART21: How did the title for the Black Monolith series originate?

WHITTEN: From the back porch at my house in Greece, I can see a huge rock that is up in the mountains. It’s a monolith, rising out of the earth, and that damn thing has really inspired me over the years. Back in the early 1980s, the Black Monolith idea came out of that massive rock.

The Black Monoliths begin with a subject, a Black person who has contributed a lot to society. I plan to do the series for the rest of my life because the Black community has creative, successful people who have given back tremendously to society, which is not advertised a lot. These are not simplistic narrative paintings. The story’s in the paint.

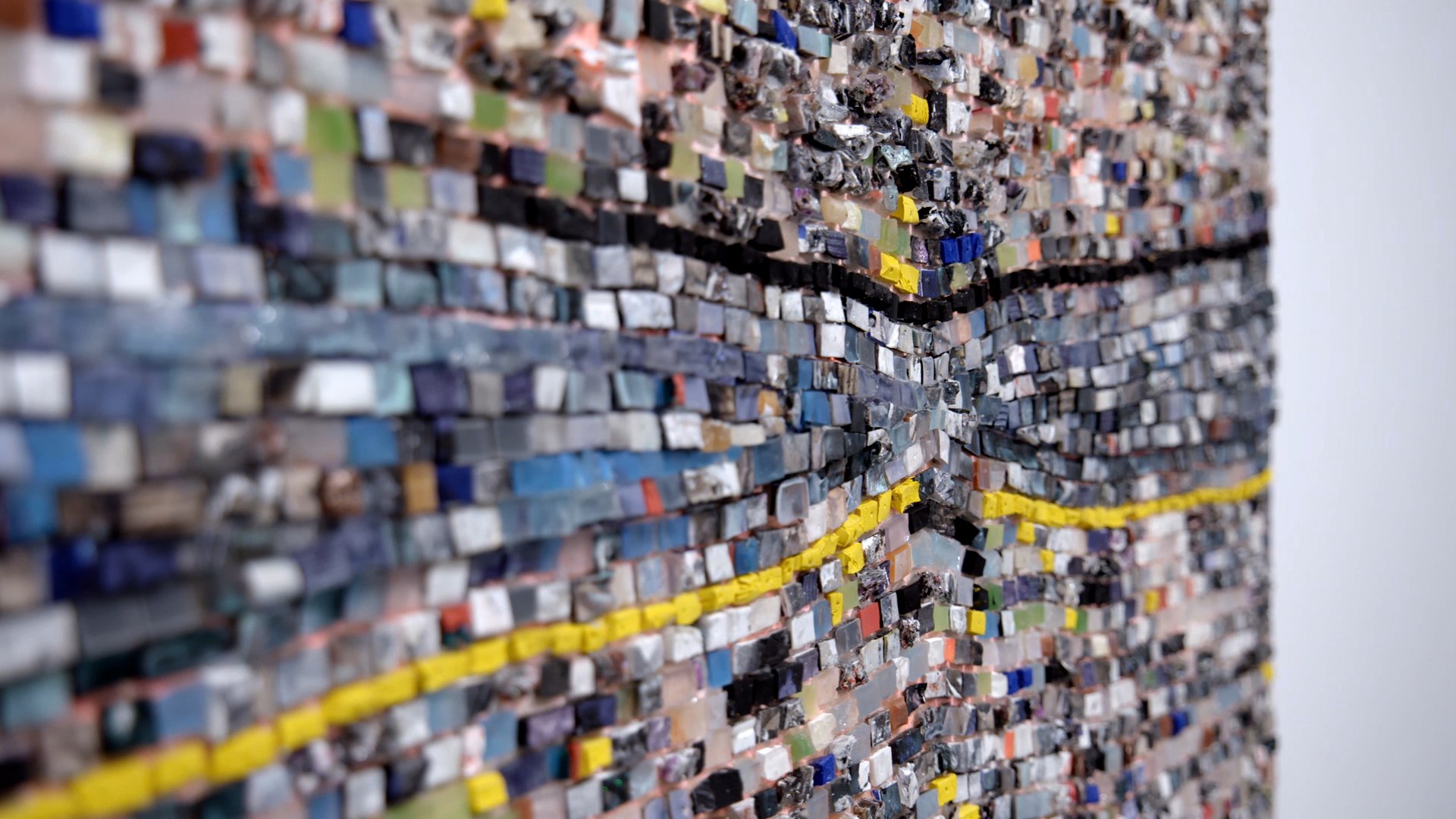

Detail of Jack Whitten’s Quantum Wall, VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love In Painting), 2017. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, Jack Whitten: An Artist’s Life. © Art21, Inc. 2018.

ART21: While you are making a painting, do you quickly decide which mosaic piece to pick up?

WHITTEN: Once I get into the rhythm of it and am working with no distractions, it’s a flow. Once I get into the flow, I don’t have to think about it; my eye reacts to the specific density [of a piece].

ART21: What’s kept you going, through the decades?

WHITTEN: It’s the life force, of wanting something that exists outside of dualities. That’s what keeps me going.

An excerpt of this interview was also published in the Art21 Magazine’s Spring 2018 issue, “Rights of Passage.”

Interviewer: Ian Forster. Content Editors: Lindsey Davis and Deanna Lee. Published: April 2018. © Art21, Inc. Artwork: Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York.