Interview conducted for Art21 in January of 2020 by Ian Forster and edited in March 2023 by Carina Martinez. To learn more, watch “Michael Rakowitz: Haunting the West.”

In the Studio

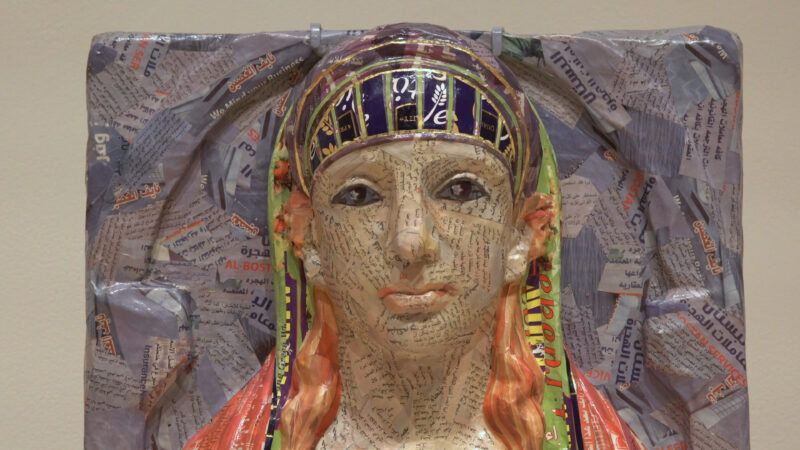

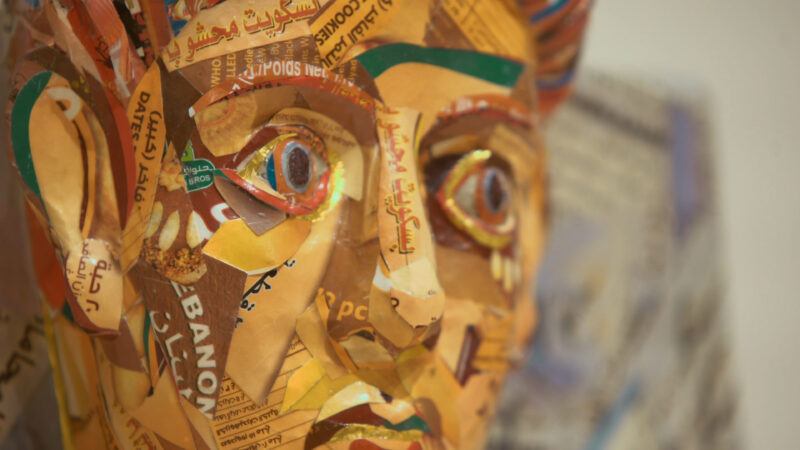

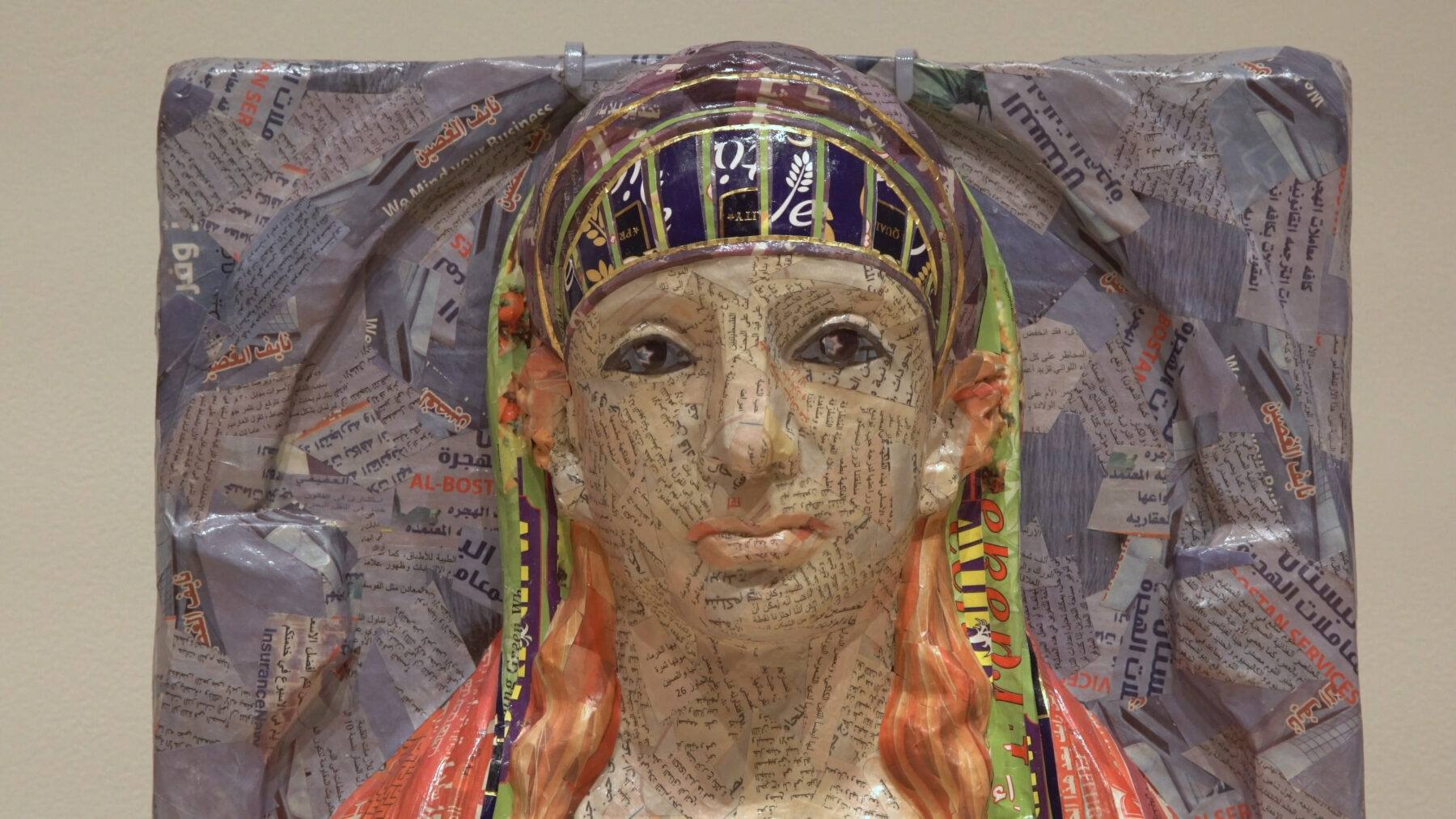

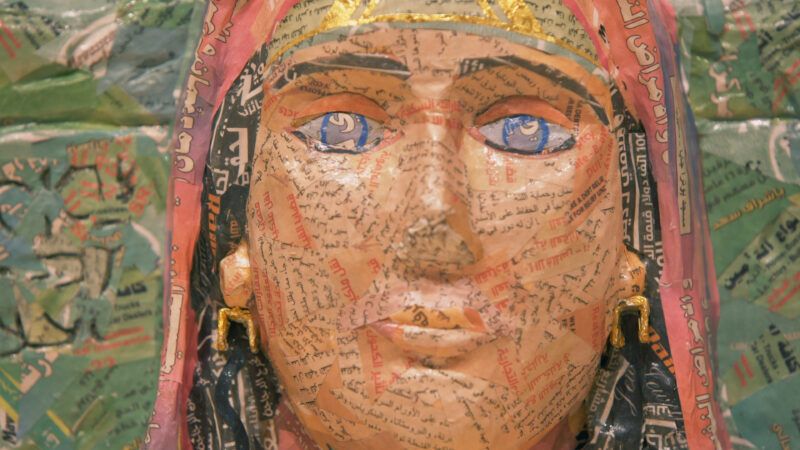

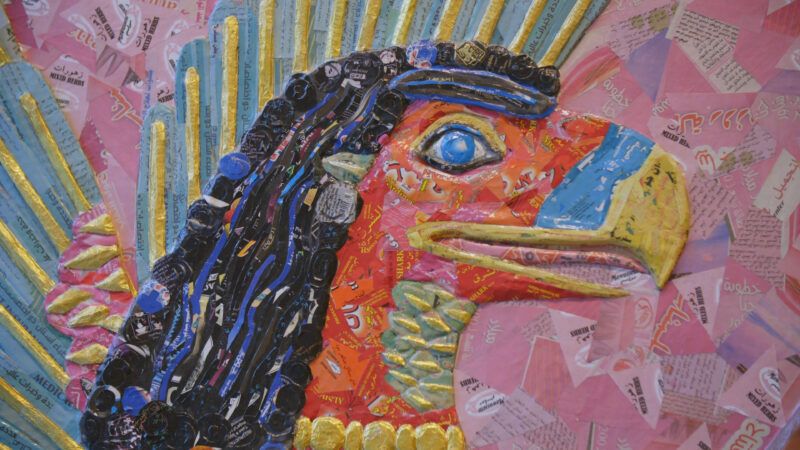

Michael Rakowitz uses everyday objects to render lost artifacts into ghostly new forms.

Ian Forster – Could you tell me how this project began and how this particular installation is a part of that?

Michael Rakowitz –The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist began in 2006, but it’s a project, I think, that began before that in 2003. In the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq, the National Museum of Iraq was looted in Baghdad from the 10th until the 12th of April of that year. In that museum, you have some of the earliest examples of writing, of urban planning. It’s a primal scene of human history.

And when the outrage about lost artifacts did not turn into an outrage about lost lives, I started to think about a project with those artifacts that were listed as missing, stolen, destroyed, or status unknown on the various databases that look to inventory what had been lost from the Iraq Museum. I decided that it would be interesting to, not reconstruct, but reappear those artifacts as a spectral presence. As a ghost of what once was. And so it began as a project where I focused entirely on the 8,000-plus artifacts that are still at large in the aftermath of the looting of the Iraq Museum, but it’s also unfortunately grown to include the archeological sites that have been devastated by groups like ISIS in the wake of the Iraq War.

When that initial looting occurred, what was the international reaction?

The reaction at the moment of the looting was one where the ability for humans to focus on the direct tragedy may have been redirected through these objects. This is something that often happens through trauma—we focus on something that becomes a vessel for other forms of grief and rage. But it also is a telling moment in that it aligns with other historical moments of iconoclasm or vandalism or libricide, and the burning of books, as we know, is accompanied by the burning of people. So when we see the cultural heritage of a place being destroyed or being looted in the aftermath of a violent invasion, we start to see the ways in which that culture reflects on what’s happening. I think that the project as a whole, even with the works that are destroyed by ISIS, points to the fact that the West assigns value to the objects from that part of the world. But it’s not at all symmetrical when you consider the way in which there’s been this devaluation and dehumanization of the people that are from those places.

You mentioned a few times now that ultimately what you’re most interested in is the people, and, of course, it’s very personal for you. Can you talk about this work’s connection to your family background?

Okay. So, my mother’s family was from Baghdad. They were Jews that lived in that city and were put in a position where they had to leave in the mid-1940s. And they were proud to identify as Arab Jews. The house that they had in New York when they left the Middle East was set up so that they could transmit this culture that they were heartbroken to be torn away from. And those aromas, that evidence of human gathering and conversation and warmth in the family, was something that filled this architectural space in a way where I was mesmerized. That really laid the groundwork of having some understanding of who we were and where we were from, but it wasn’t exoticized. It wasn’t something that felt in any way alien to me, and I think that’s evidence of the fact that my grandparents were able to do what I think a lot of immigrant families try to do, which is how do you preserve where you’re from when you’re forced to move to somewhere else?

This was something that I saw reflected so much in the commodities that one finds throughout grocery stores in the United States and in cities like New York, which I grew up in close proximity to, specifically Sahadi Importing Company in Brooklyn. There was one moment in particular that frames my entire practice, when I was in the store in 2004, and saw a big red can of date syrup that had Arabic writing on it that said ‘product of Lebanon.’ And I thought to buy this for my mother, because date syrup is actually something that’s very important to Iraqi cuisine and we grew up around it.

I walked up to the cash register, and the owner of the store, who knew my grandparents when they first immigrated from Iraq, said to me, “Your mother’s going to love this. It’s from Baghdad.” I looked at the can and it said ‘product of Lebanon.’ And I wondered what was going on, what was this strange geography lesson? He said to me that the date syrup is actually processed in the Iraqi capital, put into large plastic vats, then driven over the border to Syria, where it gets put into these unmarked tin plate steel cans, and then it’s driven over into Lebanon, where it gets labeled and is sold to the rest of the world. And this was one of the ways in which the Iraqi date syrup industry survived during the years of the sanctions, from 1991 until 2003.

But this was 2004, a year after the sanctions had been dropped, and I wondered why it was still in place. The owner said to me, “Because of the prohibitive charges from US Homeland Security, for anything that is coming from a place like Iraq or Afghanistan, it would be too prohibitive for somebody to import it. And therefore, it would be bad business.” And I said, “Well, it could be good art.” And so that birthed Return (2004-Ongoing), a project where I reopened my grandfather’s import-export company that he operated in Baghdad, and I operated it here in Brooklyn with the chief directive to import Iraqi dates to the US for the first time in 40 years.

Through the import-export industry, I started to learn about all these commodities that were too scared to tell you where they were from. It was almost like the pressures of xenophobia were being exerted on the object itself. And it was in that moment, when I was operating what was basically an empty store in Brooklyn, that I started to think about the emptied out museum in Baghdad. And when I started to think about the object in the vitrine in the museum, which holds its value because of where it comes from, I thought about the date syrup and date cookies not being able to tell you where they were from. I thought that was the skin that these artifacts should have to wear when they come back as ghosts. That’s how they should appear: in this urgent, vulnerable materiality that is about people having to leave that place and then what they do to survive. Not just to keep breathing, but to keep living a life where they feel like they’re still belonging to a place while also pointing to the fact that they are no longer there, and not by conditions of their own making.

What other materials are the objects in the installation made of?

These reliefs themselves continue the material culture of the larger project, which is to use the packaging of Middle Eastern food stuffs and Arabic English newspapers that are found throughout the United States in different groceries, which are often gathering spaces for a lot of families who come from places like Palestine, Syria, Iraq. In those places, where they get the spices and different ingredients to continue to make their cuisine, they also get these Arabic English newspapers that are given away for free. And so that newspaper shows up in these reappearances as well. One of the things that’s interesting about the particular focus on the Northwest Palace of Nimrud is that it was built by an Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal the Second in the middle of the 800s BC. And the places in Chicago where I gather the materials from are operated mostly by immigrants from Northern Iraq, so they are the direct descendants of the people that made the original reliefs. And so there’s this nice circular economy, that the hands that made these in the first place are being resurrected in some ways, are being reanimated by the professions that their descendants have taken on in this new part of the world.