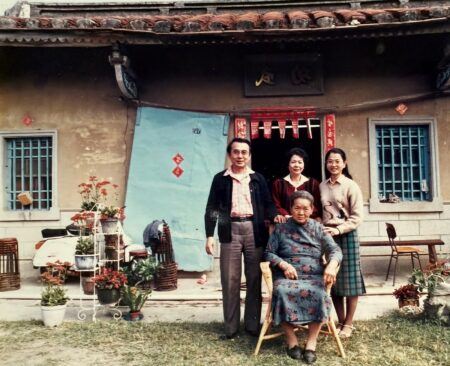

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 11 episode, “Bodies of Knowledge.” © Art21, Inc. 2023.

How do you define craft? For me, craft started with making a friendship bracelet, a seemingly forgettable girlhood activity, braiding strings of neon colored plastic to adorn my BFFs and me. That was the first time, and one of the few times, I made something that I could use in a practical sense that I did not have to purchase. Although it was just a bracelet, this was one of the first instances I recognized my relationship to an object: it was something I made in communion with my girlfriends; the bracelets were not only functional, but beautiful and imbued with the meaning of friendship.

Like defining contemporary art, defining craft is the least interesting part of the conversation. However, the definition of craft that I have found most useful combines the words of several scholars and artists: craft is the skilled and thoughtful act of process and/or material-oriented making. Examples of craft may include weaving, pottery, motherhood, writing, and community organizing, among other things. The recurring terms used to describe craft are the words skill and care, referring to the ethos of doing things well for the sake of doing it well. That can mean knowing the history of clay as a ceramicist, understanding the science of the kiln, and expert knowledge on how to manipulate dirt and water. This working definition can also include the work of a nursing aide, who knows their patients’ needs and how to use certain tools to resolve those needs. A line cook shows this same affection, care, and expertise when gutting a fish. A deep understanding and knowledge that can be both formally or informally learned is at the core of craft.

Throughout the 20th century, museums, historians, and curators struggled with what to do with craft and, at several points, moved away from celebrating artisans and simply tucked craft into the belly of fine arts. Craft’s inability to find a home in the art world may be the reason it has been attractive to activists. We can look to contemporary craft artists like Tanya Aguiñiga, who leverages weaving and craft history to connect the stories and issues concerning migrants crossing the Mexico and United States border in her Border Quipu project. Using fabric and knotting as a readily accessible material and technique, Aguiñiga is able to repair and merge seemingly disparate moments of displacement, frustration, yearning, and longing through the literal act of knotting together the writings of migrants’ stories. Aguiñiga not only taps into the history of craft as a universal language through quipu–an ancient Incan communication practice of making legible knots–but her work also speaks to the lineages to which craft can uniquely extend its arms. In the Extended Play episode “Crafting Lineage,” Aguiñiga states, “when I studied craft, you know the lineage of who taught who… which is something that I think a lot of us whose parents migrated, we don’t have lineages. I know my grandma’s name and that’s it.” Through learning furniture design in college and being welcomed into a network of furniture makers, Aguiñiga found craft as a site of alternative education that welcomes creatives without traditional artist legacies.

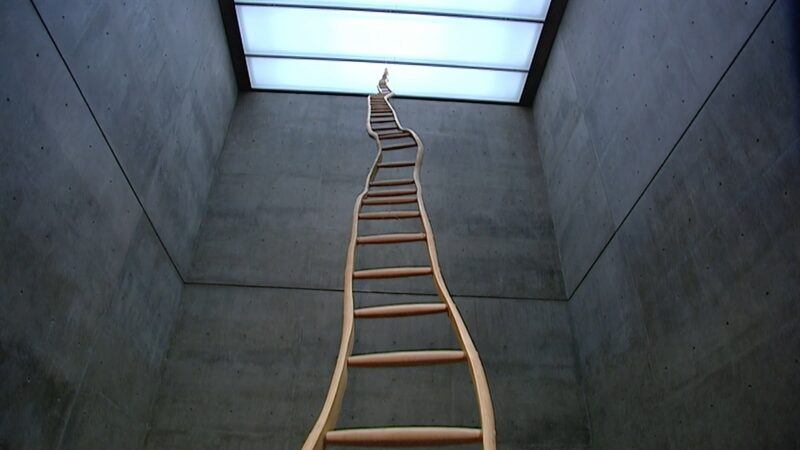

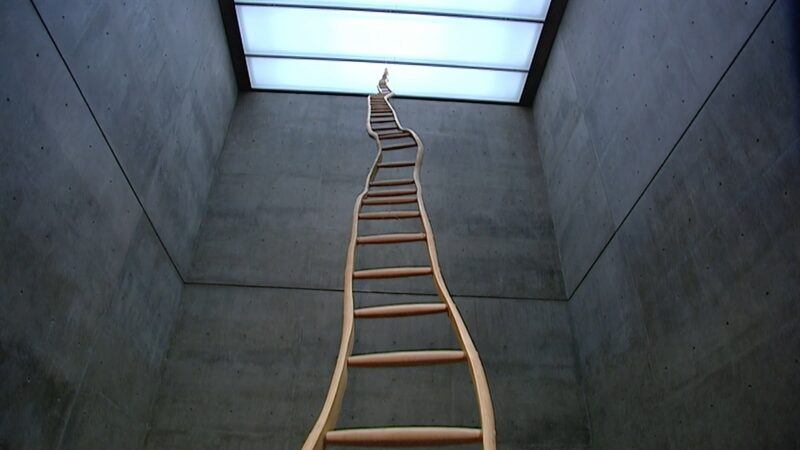

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, “Time.” © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Social justice and craft education have long been interwoven. In the episode “Time” in Season 2 of Art in the Twenty-First Century, Martin Puryear reflects on his work, Ladder for Booker T. Washington. The work is an object symbolizing the legacy of Booker T. Washington as an advocate for radical craft education that celebrated the marriage of craft, labor, and joy as black liberation. A similar interest in craft education inspired Josiah McElheny to pursue glassblowing. In the Season 3 episode “Memory” he remarks, “I was interested in this idea of being an apprentice… It involved working with other people and I like that aspect of it. You can’t stop in the middle, it’s like playing a piece of music.” Like Aguiñiga and Puryear, McElheny is drawn to the community of craft and the collaboration it requires. Although craft has been a footnote in mainstream art history, contemporary artists continue to see the value in craft as a historically rich and relational practice that can respond to our current moment.

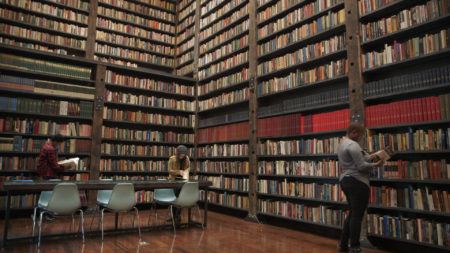

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, “Memory.” © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Craft cannot be equated with one singular object, practice, or material. It is a living organism that adapts to technological innovations, politics, and changing labor practices. Namita Wiggers, craft scholar and writer, once told me that “Craft is messy.” Contemporary artists are the most adept at breaking boxes and revel in defying and challenging limitations and restraints.

Watch Makda’s playlist, “Craft and Contemporary Art.”

Makda Amdetsyon is an educator, researcher, and maker. She joined Art21 as the Education Coordinator in June 2024. Makda comes to this role with a background in facilitating reflective and inquiry driven museum visits and artmaking classes for K-12 students and teachers at the Brooklyn Museum. In addition to her work as an educator, Makda is experienced in artist engagement and communication. During her time at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, she interviewed artisans and co-produced public programs for the annual Folklife Festival. Makda’s work as a researcher focuses on craft, bridging her art practice and academic studies on American craft and material culture.

Makda is also a textile artist and sewist. She has spent the past several years honing her craft in weaving, dyeing, and sewing at craft schools across the country. She holds a BA in Communications from University of Maryland, College Park and an MA in Art, Education and Community Practice from New York University.