Production still from the Extended Play film, “Song Dong: 生 / Shēng.” © Art21, Inc. 2022.

As an art history educator, I have enjoyed finding ways to make personal connections with artists from the past with artists of the present. When starting a new school year, I continuously ask myself, “How can I promote connection with other people (even those who have passed on)? What kinds of conversations, experiences, and activities might help students to be in someone else’s experience? And how can I facilitate space for honest reflection on humanity’s deep connection with each other across space and time?”

The Art21 bank of artists has provided a real-time insight into the artist’s mind for my students, especially those who don’t practice art-making. Contemporary artists through these videos have allowed my students to see and hear how art-making connects to real-life experiences. We get the benefit of hearing the minds of these artists who unabashedly showcase the breadth and depth of their curiosities, concerns, and motivations before, during, and even after a product is done. By using contemporary artists who possibly paralleled the walks of artists from art history, my curriculum is illuminated because it closes the gap between past and present. For example, I love to make parallels like Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s writing practices with medieval manuscript writer’s poetic and provocative illuminated texts revealing the complex relationship between God and people.

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kameelah Janan Rasheed: The Edge of Legibility.” © Art21 Inc., 2021.

Teaching College Board’s 250 works from AP Art History is an insanely limiting process, but I admit that though it has its frustrations, it does provide us with a foundation for how to start talking about art from a historical and critical lens. Paired with Art21’s artists, I am able to usher in teaching content that appears to be static from a contemporary lens. The required list of 250 works of art establishes a foundational visual language for understanding art and often introduces students to engaging with diverse cultures through their art/art-making processes in under 10 months!

For example, when learning the Paleolithic unit during our first week of school, I have students imagine living off of the bare minimum and crafting small figurines as ways to preserve meaning while venturing through an unknown world filled with gigantic beasts, wild flowers, and jagged terrain. The Venus of Willendorf was a handheld sculpture, possibly crafted for a traveler’s comfort. Maybe it was for a young girl praying for fertility or for a young person holding onto the memory of their lover. Regardless, this small figure served a purpose. Teaching in this way contrasts the stoic and artificial approach normally taken when teaching prehistoric objects. The standard inquiry of “What do you see?” is not enough to ignite critical thinking. I believe that it better serves our students to ask, “Who made this, who needed this, and why?” Curiosity is central to the learning process. Now, students aim to question why the craft, carving, and carver exist. They are expected to relate who they are and investigate how we function as independents and as a collective in society, i.e. making deep human connections across space and time.

I structure my year by culture, themes, and time, but I make contemporary connections throughout the course of the year.

My units are:

- Prehistory/Africa/Pacific

- Ancient Near East and the Mediterranean

- Early Europe

- Medieval Manuscripts and World Religions

- West, Central and East Asia

- Indigenous and Colonial Americas

- Later Europe and Art Movements

- Modernism

- Contemporary

I’ve found that this format allows students to get a wide range of art upfront, then it takes them into periods of concentration with specific cultures, and then it ends with students making broader thematic connections while using learned artworks from the beginning of the year. Shout-out to Yu Bong Ko, my AP Art History professor from Manhattan College, and his friend Doug, for helping me to develop a format that has worked for the last 3 years (and, surprisingly, also secures a 2-week review period before the AP Exam!). In my school district, my curriculum only spans 8 out of the 10-months allotted, which starts in mid-September and ends in late April. It’s definitely a fast track experience through art! Since it’s so fast, I have to consider opportunities for connection: personally, societally, and conventionally.

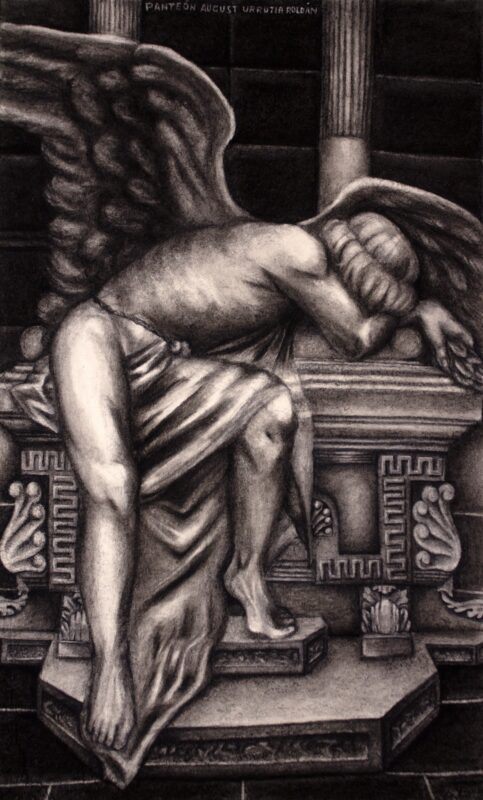

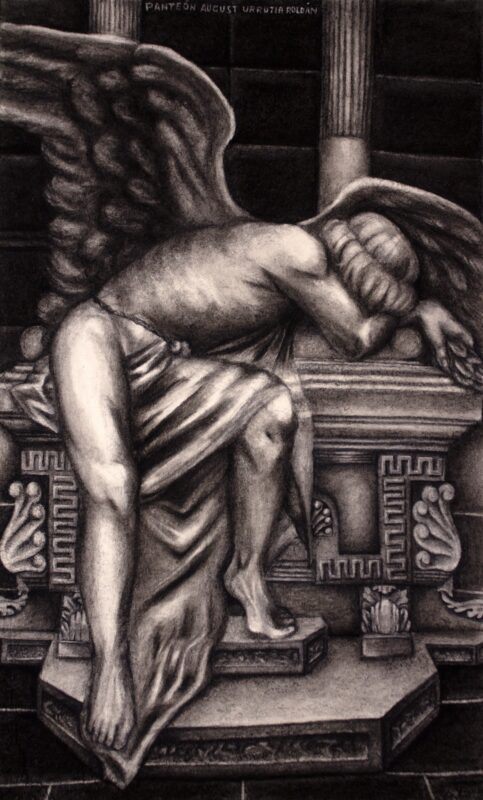

Artwork by Caroline Shaw, CHS Student. Courtesy of Kandice Stewart.

When considering which artists use history to inform their work, several artists come to mind, but my goal is to listen for stories of personal connections. Artist Song Dong is at the top of my list for ways to start my year in art history. Song Dong in his Extended Play film says, “We paint something, we write something, because we want to remember it.” This thinking is the foundational philosophy for meaning-making for my students. Song Dong’s account helps to introduce art pieces like the Apollo 11 Stones or Tlatilco figurines because he charges his audience with deeply considering ideas around impermanence, memory, and storytelling.

Historically, whether an artist moved quickly with a paintbrush across a stone like Song Dong or grabbed a withering piece of charcoal to record leaping bundles of horses within the Caves of Lascaux, the intention of capturing an experience reverberates through time thus preserving a memory of our universal condition of forming relationships through art-making. In these scenarios, it might have been a relationship with the self, the physical world, or with someone else. Song Dong promotes that it could be the combination of all 3. I like hearing my students grapple with why they make, why they presume others create, and how humanity is viewed from this lens of meaning-making independently and collectively.

After watching the video and learning about a few prehistoric works of art, I ask my students, “Why? Why capture this moment? What’s the point?” And as a follow-up, based on what was captured, “What have we learned about the artist and their world?” And when they leave my classroom, I ask them to deepen their knowledge with a request: “What will you capture today?”

Watch Kandice’s playlist, “Connections Across Space & Time: Rethinking AP Art History”

Kandice Stewart is based in the Greater New York City area and lives in New Jersey. She believes that art is love, connection, spirit, energy, life, and healing. Kandice states that she is human first, while also being an educator, mother, caretaker, sister, activist, enthusiast, explorer, student, and collaborator. She has been teaching for over ten years mostly in communities of ethnically diverse backgrounds due to her deep passion for equity and inclusion. She aims to use her work for personal, community and global activism.

Beyond being a proud mother of three amazing human beings, she is a Doctoral student at Columbia University studying teacher identity development in the public sector, and she is a full-time AP Art History and Studio Art teacher at Columbia High School. She has partnered with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, University of Florida’s Art Education program, and the NY Historical Society to offer ways of knowing and sharing the expansive human experience through art. Currently, she helps other Art educators through Teacher’s College, CCNY City College, the Art of Education University, the Academy of Fellows, and Art21 Educator programs to think critically and creatively about their personal arts praxis and pedagogy. She believes that art is the present opportunity to connect with yourself, others and the world.