Interview

“The Rwanda Project”

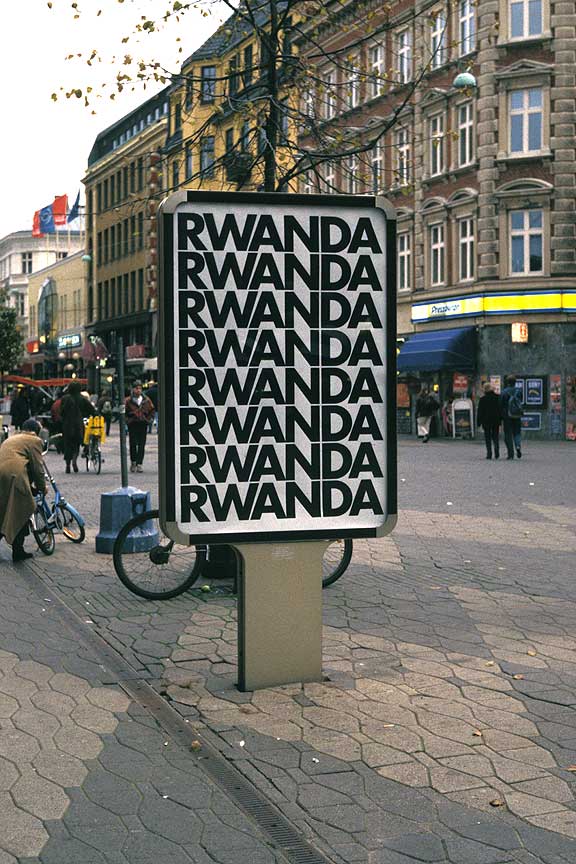

Alfredo Jaar. Rwanda Rwanda, 1994. Public intervention in Malmö, Sweden. Offset print. 68 1/2 x 46 1/2 inches. Edition of 100. © Alfredo Jaar, courtesy of Thord Thordeman, Malmö, and Galerie Lelong, New York.

Alfredo Jaar discusses his works Rwanda Rwanda and The Silence of Nduwayezu, both part of the artist’s six-year Rwanda Project.

ART21: Why did The Rwanda Project take you much longer to make than any of your other projects?

JAAR: It was my most difficult project. That’s why The Rwanda Project lasted six years. I ended up doing twenty-one pieces in those six years. Each one was an exercise of representation. And—how can I say this—they all failed. But I learned from each. And I used the lessons from one exercise in the next.

This work, in particular (I think it’s number 15 or 16 in the entire series about Rwanda), the strategy here was to reduce the scale of the tragedy. Basically, when we say, “one million dead,” it’s meaningless. So, the strategy was to reduce the scale to a single human being with a name, a story. That helps the audience to identify with that person. And this process of identification is fundamental to create empathy, solidarity, and intellectual involvement.

So, that’s what this piece is about. The text at the entrance tells you a story, and here we have the visual articulation of that story. I’m trying always to create a balance between information and spectacle, between content and the visuals. I think that balance is very difficult to reach. But the only way for you not to dismiss this image is to understand the story. If not, it becomes just another image. So, it was very important for me to create a truly memorable image, a memorial for the people of Rwanda.

ART21: What is the balance you are trying to strike with your work?

JAAR: I always try to incorporate an intellectual and emotional element because I like to create different entry points for the audience. I’m concerned about communication; this is my goal. I didn’t want to take the risk that this work would stay just on a visual level, so I needed the information. But obviously I agree that a lot of people might enter this place and just be overwhelmed by the scale of this representation.

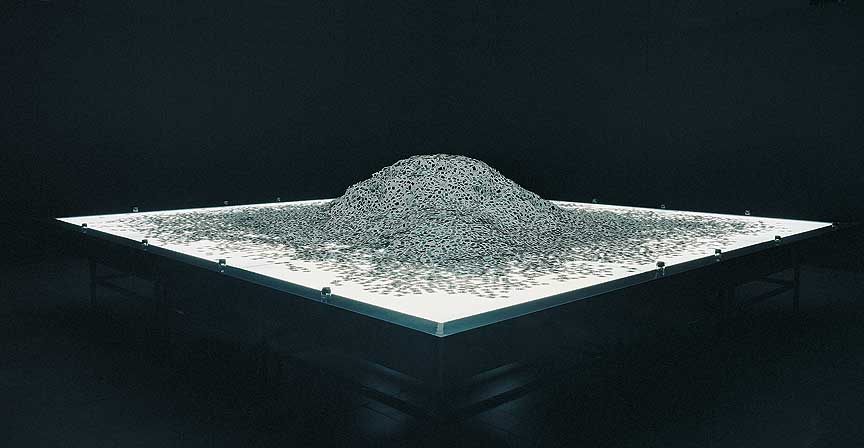

Alfredo Jaar. The Silence of Nduwayezu, 1997. 1 million slides, light table, magnifiers, and illuminated wall text. Table: 36 inches × 217 3/4 inches × 143 inches. Text: 6 inches × 188 inches. © Alfredo Jaar, courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York.

ART21: Say more about the Rwanda piece, The Silence of Nduwayezu.

JAAR: I think this is a work where we can clearly see the ethics and the aesthetics. And it has a very strong emotional charge, no doubt about it. But I think that it might fall into the generic. I think that the text directs it more in an ethical direction, on the political side. It is more specific: it talks about a country, a continent, criminal indifference from the world community. So, in a way, the text here is the intellectual backup that I need, to make sure that this is not just generic suffering. But these are my own obsessions. I’ve shown this piece quite a few times, and I’ve become aware of its power and impact. But I’ve seen people coming in and ignoring the text because they’re impatient. They just want to see what’s in here. And it’s with pleasure that I see them going back and reading the text, saying, “What is this?” I think I’ve managed to create an emotional charge, but I’m really interested in going deeper than that.

ART21: How do you hope people will understand this work?

JAAR: Of course, I’m interested in people making all these connections and projections. It’s really part of the program of the piece. But I think it’s important that there is some specificity as a starting point. Of course, people will make many different connections, many different projections toward all the horrors of these last two or three centuries, and that’s perfectly fine. That’s really part of the piece. I’m not at all against that, and I think the piece encourages it. Unfortunately, we have had quite a few horrors to refer to.

ART21: Can you talk about the way the slides are heaped on top of each other?

JAAR: Well, it just happened like this: I wanted to create a volume that represented approximately one million slides, in reference to the one million dead in Rwanda. Some people interpret it as a body; others see a country’s landscape. But basically, it’s just sheer accumulation that in every place takes a different shape. And people will make different associations.

ART21: So, there is no underlying form?

JAAR: No, this shape was created in a very spontaneous way, as we unwrapped the slides and just accumulated them on the table.

ART21: Are there different ways people understand this shape?

JAAR: For example, in Chile, this shape would immediately suggest the Andes, the mountains surrounding Santiago. And then this will automatically connect the work with the Chilean situation. But this is not calculated into the work. In other places, where maybe they don’t have such a strong landscape, they will look for the bodies in this shape. So, it really has to do with the projections that the audience will make.

ART21: Does your training in architecture inform this work at all?

JAAR: Because of my background as an architect, I design every work based on a program. The program here was to tell a story in a very dark space and to enter a space of light where, instead of light, we find another kind of horror. Sometimes, light is liberating and light is hope. Here, light is horror. It reveals the eyes of this kid who witnessed a genocide that we did not want to witness. I’m interested in that moment when the audience takes a look. They look at the eyes very carefully, and that is the moment I’m looking for—when their eyes are a centimeter away from the eyes of Nduwayezu, who witnessed what we didn’t want to see.

ART21: Who is Nduwayezu? Can you tell us more about his situation? Why did you decide to represent only his eyes in this work?

JAAR: I visited a refugee camp, and Nduwayezu was seated on the stairs of a door. I discovered very quickly that all these kids were orphans that had witnessed how their parents were killed. Nduwayezu actually saw his mother and father killed with machetes. His reaction was to remain silent for approximately four weeks. He couldn’t speak. His eyes were the saddest eyes I had ever seen, so I wanted to represent that and speak about his silence. Because his silence refers to the silence of the world community that let this happen.

Alfredo Jaar. The Silence of Nduwayezu, detail, 1997. 1 million slides, light table, magnifiers, and illuminated wall text. Table: 36 inches × 217 3/4 inches × 143 inches. Text: 6 inches × 188 inches. © Alfredo Jaar, courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York.

ART21: How do you begin creating a piece like this one? What’s the process?

JAAR: I’ve never been capable of creating a single work of art that just comes from my imagination. I don’t know how to do that. Every work is a response to a real-life event, a real-life situation. That’s why I always describe myself as a project artist. I’m not a studio artist; I do not create works in my studio. I wouldn’t know what to do. I do not stare at the blank page of paper and start inventing a world coming from my imagination. My imagination starts working based on research, based on a real-life event—most of the time, a tragedy—that I’m just starting to accumulate information about, to analyze, to reflect on. But the original impulse is the event to which I’m trying to respond.

ART21: You spend a lot of time absorbing the news and understanding what’s going on in the world. Was this an important starting point for the Rwanda work?

JAAR: I’m obsessed with information. A few years back, I was always reading five, six, ten newspapers a day. Sometimes in New York, they would come a day late. Today, with the Internet, it’s much easier. I start my day early in the morning, spending maybe an hour, or an hour and a half, looking at the news. I’m interested in the world. I’m fascinated by what’s happening in the world. There is no fiction better than this reality that surrounds us. So, I analyze the news. I’m interested in the way different media convey the news.

In the case of Rwanda, I followed the tragedy from the beginning. I was outraged at how we were told this was happening. “Yesterday, 35,000 bodies were recovered; they were floating on the Kagera River.” Thirty-five thousand bodies—and it was just a five-line story on Page 7. “I have to go,” I thought, “There is something I have to say about this.” It was the most horrific experience in my life. We went to gather evidence, one assistant and myself. We spent time talking to people, photographing the situation. We accumulated probably thirty-five hundred images of the most horrific things—so much so that, when I got back to New York, I didn’t want to look at them. But when I finally had the courage to analyze them, I realized that I couldn’t use them. It didn’t make sense to use them; people did not react to these kinds of images. Why would they react now? I was starting to think that there must be another way to talk about violence without recurring to violence. There must be a way to talk about suffering without making the victim suffer again. How do you represent this, while respecting the dignity of the people you are focusing on?

ART21: Can you say more about your specific interest in Africa?

JAAR: I have a very strong emotional link with Africans, and I think that is present in the way I approach my work. Africa has been exploited and now completely abandoned by the rest of the world. The United States has never cared about Africa and now, suddenly, they’re in Angola. Why? Because Angola is offering them 10 percent of their oil production.

ART21: Did you feel like The Silence of Nduwayezu finally articulated what you wanted to say about Rwanda? Was there some resolution for you in completing this piece?

JAAR: If I kept going for such a long time on the Rwanda project, it was because I was first outraged by the international community’s reaction—the barbaric indifference. It was going so much to the essence of what it means to be a human being because (as I am trying to tell you) when you witness something like this, you’re ashamed of being a human being. It’s as simple as that. You’re ashamed. So, how do you transfer this into a work of art? How? I have no idea. The Silence of Nduwayezu is one of my last attempts.