Deep Focus

A Fickle Trickster Screen

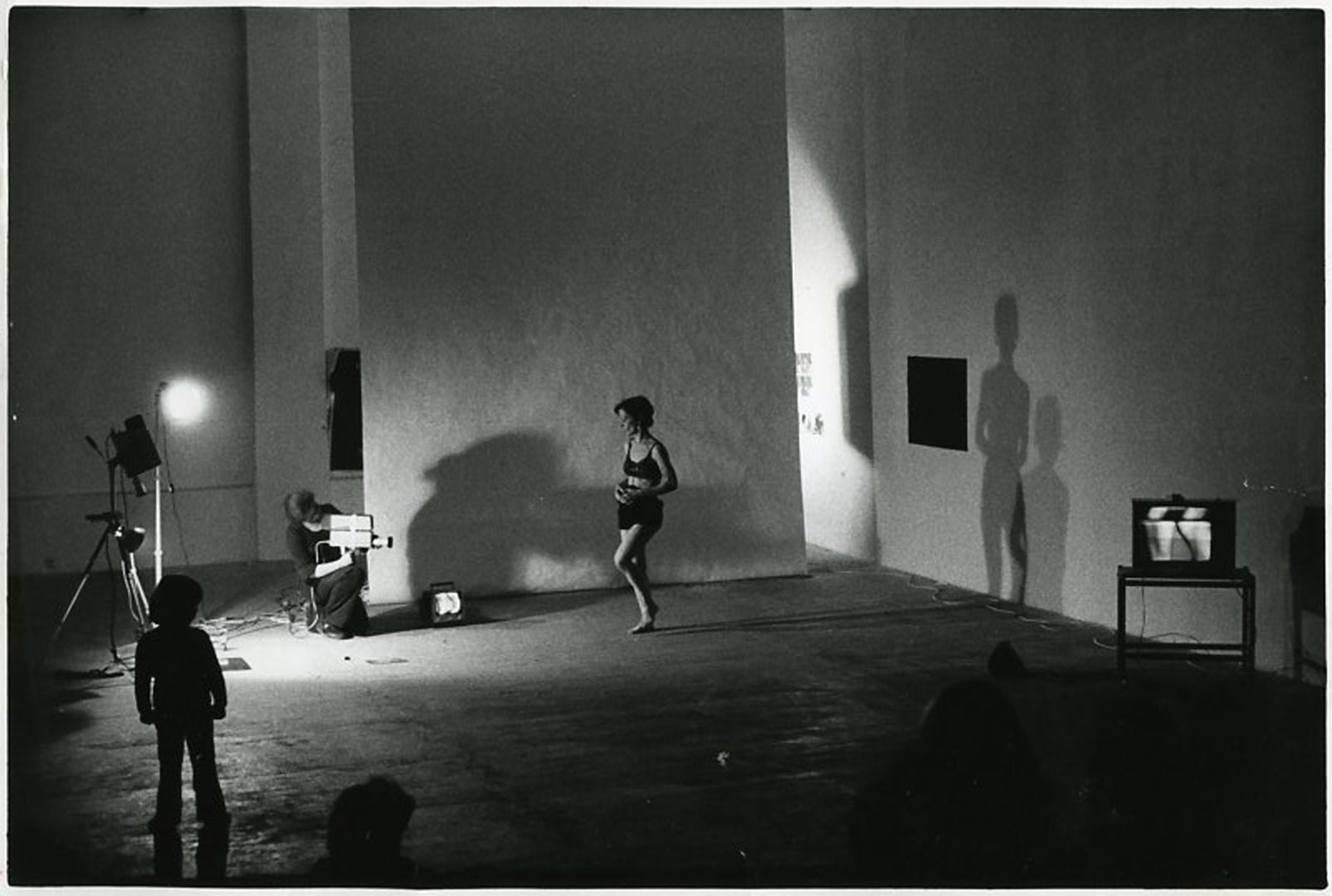

Joan Jonas. Organic Honey’s Vertical Roll, 1972. Performance at Galleria Toselli, Milan, Italy, 1973. Photo: Giorgio Colombo. © Joan Jonas.

For more than four decades, Joan Jonas’s interest in producing, emphasizing, and manipulating space and sound has remained constant in her practice. A 1972 article by Janelle Reiring in The Drama Review describes one of Jonas’s early New York performances, Delay Delay. Embedded in this review is a portrait of New York: a city with unattended, empty spaces. Delay Delay took place in “an area on the west side of Manhattan, north of the World Trade Center, that [had] remained vacant for more than two years. All buildings were leveled except for a few deemed historical landmarks.”1 Jonas marked this site with large painted numbers on multiple plywood signs, helping audience members differentiate areas of action from where they stood, a quarter mile away on the roof of a five-story building. “Delay Delay begins with performers dispersed throughout the space, and there is a gradual movement toward containment until the final exit of a tight group in the far distance,” wrote Reiring.2 Performers in the vacant lot made choreographed gestures: clacking wooden blocks at designated times and from various distances, rolling a large hoop containing a person over the terrain, or raising triangles into the air. In an interview, Jonas described how, “Carol Gooden and Gordon Matta-Clark spent the entire performance painting a big circle and a line in the street below.”3 Meanwhile, accidental entrances like “Sunday walkers, bicycle riders, [and] boats moving down the Hudson” were absorbed and incorporated in the theatrical event.4 Were it not for the clacking of the wooden blocks, the figures would appear silent and seamless to the audience; the blocks’ sounds punctuated the tableau, connecting the space between viewer and performer with different sonic delays, depending on distance. Reiring explained: “Jonas perceives the space of the performing area as a flat plane that meets the horizon. On or against that plane she superimposes a moving drawing. As distance alters perception of space and movement, the performance takes on a filmlike quality; at times performers are lost through the distance because of the changing light or background.”5

Joan Jonas. Song Delay film still, 1973. 16 mm film, black-and-white, sound; 18 minutes 35 seconds. Camera: Robert Fiore. © Joan Jonas.

What’s remarkable about Delay Delay is how its mechanics underlie Jonas’s later video, performance, and installation works. In Reanimation (2010/2012/2013), The Shape, The Scent, The Feel of Things (2005), and Lines in the Sand (2002), Jonas effectively creates, expands, and compresses space in similar ways. She draws directly onto these landscape video projections, as though to underscore that writing is an equivalent albeit older technology to that of the camera. Her use of identifiable objects—the triangle or the line, for instance—reciprocally transform and are transformed by the environments. And the performing figures—whether Jonas or others—at times emerge to the forefront of the tableau like central figures, and later become so integrated within the projection as to vanish. Whereas in Delay Delay that vanishing occurred from light and distance in the abandoned Manhattan lot, other works use mirrors and projection screens to disguise performers beneath reflections. “I work back and forth between performance and installation and autonomous video work, and each feeds into the other,” Jonas has said, making references to authors like Jorge Luis Borges, Dante, H.D., the Brothers Grimm, and Aby Warburg, alongside mythic influences as well as art and cinema histories.6 Within Jonas’s multilayered environments, the performer is like a node within a network of politics, identities, intuitions, and alternative subjectivities.

Reanimation is a performance collaboration with the musician Jason Moran, created first as a 2010 lecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, later as a performance at Documenta 12 (2012) and Performa 13 (2013), and most recently as an installation at the Harlem headquarters of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise. In the performance, Jonas reads excerpts from Halldór Laxness’s 1968 novel, The Glacier, amid cinematic projections of landscape sequences Jonas filmed at various locations (such as Iceland and Norway). Her drawings make multiple appearances in this tableau, projected either live or as images created earlier. Throughout the performance, Jonas moves between two desks: one tall and holding drawing implements, the other short and covered with assorted found and fabricated objects. Kneeling at this second table, Jonas produces sounds with the objects, periodically amplifying her vocalizations through a microphone. Jonas also tends to other activities: putting on a fox mask and dancing, crumpling a large ball of paper, drawing on the wall with an ink-tipped stick, or crossing the stage to her writing table where she draws on its surface, such that the viewers see the result projected onto a nearby video screen.

Joan Jonas performs Reanimation (2012) at Norrlandsoperan, Umeå, Sweden, 2013. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 7 episode, Fiction, 2014. © Art21, Inc. 2014.

Moran’s score propels and supports this non-narrative sequence, establishing a sonic environment that again, reciprocally transforms and is transformed by Jonas’ action. Jonas consistently destabilizes the audience’s perception of space and the figure’s relationship to it. As a mountain appears on the projection screen, a viewer assumes it exists at a certain distance, but the illusion is quickly shattered when Jonas begins to draw over the mountain, accentuating the surface of the image; any depth it boasts is an illusion. Yet one must also consider the surfaces of the desks that, being perpendicular to the projection screen, are not accessible to the audience. Rather, these surfaces are there for the artist to work upon, and they point to another space, one of the maker’s process, the inner workings of which cannot be fully discerned even if the audience witnesses it employed. Similarly, the audience must reconcile multiple time frames: those captured in the video and the one Jonas enacts through live drawing. Other temporal multiplicities arise: the time signature of the music, the life span of bees and flowers. In this way, Jonas is constantly disrupting a singular point of view and thereby points out the interaction of multiple frames of reference. Perhaps what is so astonishing is the cohesive experience of the work, even if it remains outside of complete linguistic apprehension. By making reference to Laxness, Jonas also includes two glacial times. The glacial subject of 1968 appears as the first point of reference, only to blur with the glacial subject of today who seems uncannily frail, eclipsed by the strange reality of our warming of the planet and its uncertain future.

Joan Jonas performs Reanimation (2012) with composer Jason Moran at Norrlandsoperan, Umeå, Sweden, 2013. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 7 episode, Fiction, 2014. © Art21, Inc. 2014.

Although Jonas was originally trained in art history and sculpture, she started working in performance and video in the 1960s. Her regular mentions of a Protopak video camera purchase emphasizes how this object determined the rest of her artistic trajectory. Unlike the male-dominated mediums of painting and sculpture at that time, video and performance were open fields for experimentation. Jonas made Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (a performance that later became a video in 1972) and Organic Honey’s Visual Role (1972); both pieces identify and locate the female subject within a mediated space. In these and other works of this period, Jonas exploits video as a medium distinctly capable of exploring subjectivity, playing with the live feed of the camera and the disorientation of mirrors and live-feed projections. For Leftside Rightside (1974), for instance, she stands between two cameras and tries to point out her left eye from her right while watching the live-feed of her efforts.

In Organic Honey’s Visual Role, Jonas explores her exotic alter ego, Organic Honey, using the camera to capture different parts of her body and clothing while in motion. These segments are at times identifiable—bare upper legs, or walking feet, or the side view of a woman’s torso—but Jonas manipulates the television’s settings to create vertical image glitches, imitating the look of a film reel. Each time the image snaps past the frame of the television screen, one hears a clacking sound, described in the score as the sound of a silver spoon with which Organic Honey hits the mirror in which she is reflected. While the space in Organic Honey’s Visual Role is tightly cropped, the body parts captured in each frame provide a different sense of depth. Further, at the end of the video, Jonas’s face appears in front of the vertically blinking image, activating a pictorial foreground that viewers would not have previously imagined.

Joan Jonas performs Reanimation (2012) at Norrlandsoperan, Umeå, Sweden, 2013. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 7 episode, Fiction, 2014. © Art21, Inc. 2014,

Great transformation has occurred between the Manhattan of the 1960s and that of today. Not only are abandoned lots hard to come by (if they can be found at all), basic access to public space is highly regulated; whereas permits were once unnecessary, they are now paramount. Today, artists who wish to live and work in the city face daunting and sometimes stifling economic realities. “In 1976,” Jonas says, “I went down at night with Pat Steir and Andy Mann, and we just improvised for the camera in the streets, on Wall Street. You can’t do that anymore. So that whole playfulness is gone. It’s not something you can do so easily, anymore.”7 These conditions do not only plague artists, but society at large and the environment we share. Consider, for instance, the staggering debt faced by students graduating from college: financial obligations make flexibility difficult so that even the most idealistic citizens have difficulty finding agency and innovation. According to this paradigm, the future is like a flat surface depicting a melting iceberg.

In another interview, she says, “I wasn’t trained in video art or performance. Nobody was, in the early 1960s. There was nothing to be trained in, because there was no tradition of video or performance; it was a totally new territory. There were artists working in dance and there were happenings, but it wasn’t a school. When contemporary American artists first started going to Europe, I remember Philip Glass saying, ‘The Europeans think we’re primitives.’ That was the advantage of being American; we were fresh, and the language was fresh.”8

Joan Jonas. Reanimation, In a Meadow, 2012. Installation at Documenta 13, Kassel, Germany, 2012. Photo: Joan Jonas. © Joan Jonas.

Although Jonas might not work in the same public, ad-hoc settings, her recent work connects live performance, drawing, and live-feed video in a circular fashion to carve out new depths. Through her hand, a room gathers multiple dimensions and temporal registers; they resonate on multiple frequencies. Her works offer questions: What is a reflection, and what is a projection? What is real, and what is imagined, and by what criteria do we differentiate the two? Unlike a magician, however, Jonas is not simply creating illusions; she also exposes the process by which those illusions are constructed. In so doing, she enacts an interesting provocation: how much of our material reality is based on collective construction? Jonas shows how the screen can be both a portal and a mirror, how it can expand into space just as easily as it hardens into a surface, and how it can reflect and advance light. If the current reality is closing off so many freedoms and futures, why not rework this stage? Let us challenge the paradigm—inscribe new drawings, texts, and relationships—to find new horizons for experimentation, sustainability, and play.

1. Janelle Reiring, “Delay Delay,” TDR/The Drama Review 16, no. 3 (September 1972, “Puppet” issue), 142.

2. Reiring, 144.

3. R. H. Quaytman, “Joan Jonas,” Interview, December 12, 2014.

4. Reiring, 147.

5. Reiring, 144.

6. Joan Jonas, in Fiction segment, Art in the Twenty-First Century, Season 7, November 14, 2014.

7. “New York Performances: Joan Jonas,” Art21: Extended Play, May 6, 2015 (1:21–1:32).

8. “An Exchange between Joan Jonas, Susan Howe and Jeanne Heuving,” How2, vol. 2, no. 3 (Spring 2005).