Teaching with Contemporary Art

A Constellation of Quiet Power

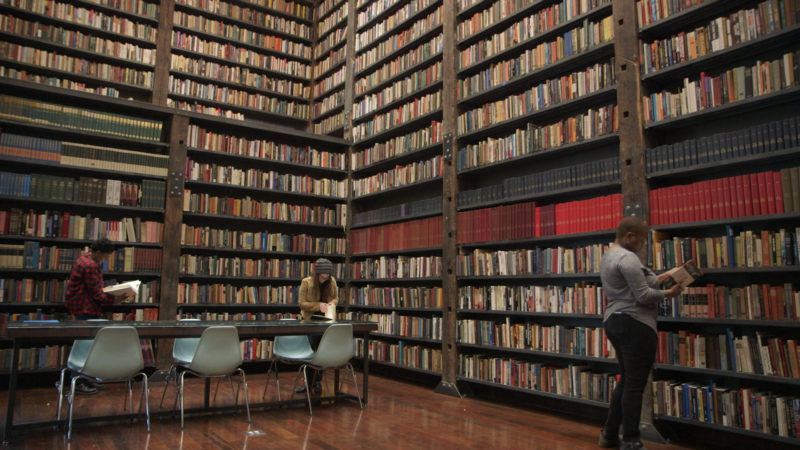

Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 8 episode “Chicago.” © Art21, Inc. 2016.

Libraries of the world offer places to spend time, reflective or otherwise, for many diverse people. Public libraries in Charleston County, South Carolina were the first places where I spoke to librarians, asking for their help with research, periodicals, and viewing microfilm. Since then, Charleston County Main Library has reimagined spaces for youth, now equipped with library specialists and a teen lounge that includes rotations of book recommendations for easy browsing, comfortable furniture, a floor-to-ceiling display of posters of artists and revolutionaries, a chalkboard wall with art supplies, and a free lunch program. Functional libraries provide welcoming spaces that inspire focus for extended amounts of time.

When I revisited the first and second floors of Charleston County Main Library in 2023 with a friend and her three children, I observed that the microfilm machines had been retired, gone were the standardized tables and chairs that had once filled the entire second floor, and a new space for young people was now visibly celebrated with friendly librarians who offered help. For early childhood and elementary-age children, the first floor hosts a large room with a dedicated librarian who supervises various activities, including a scavenger hunt that helps children become familiar with different sections of their collection, computers with educational gaming, and plenty of cozy, colorful spaces for lounging, reading aloud, and active play. I’m happy to say that my friend’s children of reading age left carrying their own very heavy tote bags filled with books. Library books ongoingly occupy designated shelves in the living room at home, at children’s height.

For me as a teen, a ride or a city bus to the Main Library secured an afternoon of pre-professional study and traveling the world through the pages of artist monographs and art magazines. Through borrowed VHS films set in New York (I believe I watched them all), I imagined a future for myself beyond South Carolina. I would argue that libraries help structure the ways that people access their interests, abilities, and each other.

Production still from the Extended Play film, “Theaster Gates: Collecting.” © Art21, Inc. 2017.

A few more memorably intentional libraries that I have visited across the world are: Zayed Central Library of Al Ain, United Arab Emirates; Central Library Oodi of Helsinki, Finland; Black Library and Black Space by Theaster Gates, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan; and Beitou Library, Taipei, Taiwan. From progressive education to a welfare state, to Black news, to nature, cultures reflect their priorities in the spaces they build.

Zayed Central Library holds a collection of over 100,000 books for children to academic scholars. In addition to an impressive children‘s library, an outdoor playground with a zip line is nearby. Central Library Oodi of Helsinki is a layered energy-efficient building that features: an active ground floor for events, library services, and open-seating; a middle level for technology spaces and amphitheater seating; and a third level that holds indoor and outdoor balcony seating, a cafe, and a vast children’s library. In the exhibition at Mori Art Museum, Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei, the Black Library and Black Space is a protected interactive library of thousands of publications on Black art, history, and culture that fill shelves on gallery walls; couches are available with select copies of magazines to peruse by hand. Beitou Library, designed by Bio-Architecture Formosana and known as Taiwan’s first green library, is located beside Beitou Hot Spring Museum in Beitou Park. The two-story wood and steel building opened in 2006 and features a green rooftop partially covered with solar panels, a wooden balcony, and large French windows that conserve energy by enabling the use of natural light. Wooden floors creak as library-goers traverse them.

Particularly special is the ability to request an appointment to view Harriet Tubman, the Moses of Her People, Golden Legacy: Illustrated History Magazine #2 by Joan Bacchus Maynard and Tom Feelings at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallace Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building of the New York Public Library and listening to artists such as Zadie Smith and Chimamanda Adiche speak at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Production still from the Extended Play film, “Arthur Jafa: Sequencing the Notes.” © Art21, 2025.

Arthur Jafa speaks about psychic architecture, visualizing Black music as an architecture, and traversing the complex landscape of Black experience as an opportunity to levitate. He asks, “How do you make a thing of beauty?” and defines a thing of beauty as “the thing you want to look at.” What does a world in which Blackness is centered look like? How do we understand our relationship to time and place relative to multiple histories and perspectives?

These questions and currents of aesthetics parallel experiences of Jafa’s film life, love, and death. Much in the way a sequence of images is miraculously arranged by Jafa “to surface relationships that wouldn’t otherwise be available” and to make visual or to go toward an “immaterial expressivity” along corridors and screens of contemporary art and music, experiences of shared spaces and power structures—and their irrevocable social impacts, emotional and physical—are remembered.

Artist and graphic designer Emory Douglas produced The Black Panther Newspaper as the party’s first and only Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture during the 1960s and 1970s. The weekly newspaper distributed more than 400,000 copies at its peak. Through the creation of prints, posters, cover art, and illustrations, Douglas was committed to the representation of Black people, their search for civil rights, their involvement in electoral politics, and their development of social programs such as health clinics, free breakfasts for children, food banks, ambulance services, and transportation services (92-115, Gaiter). This legacy of documenting the collective search for spaces of truth-telling, art, and production lives on in the work of Shani Peters, Joseph Cuillier, and Kameelah Janan Rasheed, three artists, academic professors, and designers of contemporary art education for youth.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed in her studio, Brooklyn, NY, 2021. Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Kameelah Janan Rasheed: The Edge of Legibility.” © Art21 Inc., 2021.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, an interdisciplinary research-based visual artist, writer, and former high school history teacher, creates public art, installations, and learning environments that unravel language in site-specific ways. The Black School, created in 2016 by Shani Peters and Joseph Cuillier, reimagines classroom designs for art-making workshops that mobilize Black histories and social movements of the United States as a way of arriving at self-determined and community-determined knowledge production. Together, Rasheed and The Black School formed a 2018 collaborative exhibition at the New Museum titled The Black School × Kameelah Janan Rasheed that featured prototypical classroom designs and an interactive library (on view for about four months). Also provided was a panel discussion with the artists, a variety of workshops, and two potluck family meals for sharing histories and futures of independent Black schools.

On one exhibition wall, four silkscreen-printed mirrors by Shani Peters were installed like a series of windows. The mirrors feature images of people and poetry, printed in the colors of sunrises, upon the reflections of nearby viewers. On a red wall, clipped to wire grids, were portraits of youth, multimedia works of art by youth, textiles, posters, and photography. Furniture that could be experienced as soft sculpture accompanied black carpets and vertical tapestries in red and lavender velvet with fragments of patterns and images of revolutionaries designed by Joseph Cuillier. Inside the enclosure of tapestries, young people gathered together with the teaching artists. Facilitated workshops for educators and exhibition visitors took place in the auditorium of the New Museum. In groups, participants contemplated the Community Survey and designed new futures while they dually considered principles of composition and thematic values from the Process Deck, two learning tools designed by The Black School. What was exceptional about the workshops facilitated by The Black School was how restorative they felt, how much peace they induced with straightforward language and careful questions.

Alongside the combined art installation and learning environment of The Black School, an interactive library titled ECOSYSTEMS curated by Kameelah Janan Rasheed held space for a personal collection of books and printed matter about Black traditions of education, publishing, and literary art, which includes an essay by Arthur Jafa titled On The Blackness of Blacknuss : My Black Death. Also provided were copies of a free newsprint publication about the artists’ art education residencies, table space with seating, library hours, and publishing center hours. The free newsprint publication created a ripple effect, inspiring educators like myself to practice these visual art pedagogies in my own teachings. The contrast of black-and-white Xerox imagery that pulses throughout Rasheed’s art permeated the space. Also essential to the ECOSYSTEMS atmosphere were: the presence of a Xerox machine, its offer of free material copies of your chosen selections, the importance of and attention to documentation of Rasheed’s childhood scholarship, and the library space filled with people. Educators were invited to a workshop with Rasheed; we gathered around her in the resource room, listening to the sounds of her nonstop cadence of speech, soaking up her ability to intermingle connections between disparate worlds.

The Black Schoolhouse preliminary designs.

The Black School, founded by Shani Peters and Joseph Cuillier, artists and practitioners of equitable art education, is currently being built on 8000 square feet of land at 1660 North Roman Street in the Seventh Ward in New Orleans, Louisiana, homeland of Joseph Cuillier’s family and the Chitimacha people. In this historic district, Peters and Cuillier are responding to the local needs for neighborhood input and programs designed for people. The school’s architecture features repurposed industrial steel containers, reclaimed wood, and solar energy designed by Whawn Allen Architects and LOT-EK Design Studio. With reference to the historical reformations of the Washington Rosenwald Schools, the Freedom Schools, and the Liberation Schools of the Black Panther Party, The Black School is a new eternal space for building community and inspiring radical decolonization through socially engaged architecture, design, music, dance, multi-genre art-making, apprenticeships, education, festivals, and events. The school will activate a variety of cultural and educational possibilities with facilities that include an art and design studio, garden, kitchen, gallery, meditation room, digital fabrication and computer labs, and library. The school’s impact reaches people of all ages and social contexts, centering its teachings on the application of self-determination and Black Love.

In their work, the artists Arthur Jafa, Shani Peters, Joseph Cuillier, and Kameelah Janan Rasheed confront brutality, fractured families, poverty, anti-literacy, segregation, dead end employment, wrongful incarceration, homelessness, inadequate healthcare, and false historical assumptions about racial diversity, as they create spaces that inspire introspection and agency. Beyond a status quo of overlooked environmental protections and undisclosed histories, in the style of The Black School, one might ask a neighborhood: “What do you love about your community? What do you want to change about your community?” and then build the functional, if not decadent and embellished, architectures that elevate BIPOC people and their historically radical imaginations and influence.