Interview

Printmaking and Natural History Artists

Walton Ford at work on Compromised (2002–03) with printmaker Peter Pettengill at Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, New Hampshire, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Artist Walton Ford discusses his printmaking process, and the story behind his 2002 print Compromised.

ART21: While the majority of your work is in watercolor, you’ve also recently been making prints. Can you talk a little about that project?

FORD: The whole print project is the natural fruition of all the other stuff that I do. Early naturalists like Audubon or Edward Lear (a great natural history artist) or John Gould (who made all these prints in England of birds from around the world) made prints. You can go to old bookshops and see all the preparatory work that went into making folios of natural history prints. All those things started out as watercolors that were done in the field or done from nature. And they ended up as prints that were bound and sold by subscription to mostly English people, who had cabinets of curiosities or natural history collections of their own.

So, it made sense for me, since I was sort of aping all these modes of representation—that I would end up making prints that resembled natural history prints that we’re used to seeing, that Audubon had done or something. The first project that I started working on was sort of the same size and format as the Audubon prints. And they’re all birds from around the world, but then I’ve injected all my insane subject matter into that. So, it just made sense when I talked to David Kiel (he’s the curator of prints at the Whitney Museum) and he said, “I’ve been waiting for years to hear this.” He’d been watching my work, and he thought of course I had to make prints. That was cool to hear. He’s quite knowledgeable about the history of printmaking. And it just makes total sense; it would almost make no sense not to make them. And it makes sense to make them the way that Peter and I make them, because the process he uses and the press he has is probably a hundred and fifty years old. All the techniques that he’s amassed, they’re old: Rembrandt used them.

ART21: Can you describe the process?

FORD: Yeah. So, what you do with this process, basically, is—the end result, what you’re trying to do, is make a mark on a copper plate. And the copper plates are polished like a mirror. They’re very, very smooth. And after you make a mark on them, Peter puts ink on the copper and then wipes it clean with the side of his hand. The ink stays in the mark, whatever kind of mark you make. We use various means to make the marks. We can scratch the plate directly with a sharp instrument, and it will hold the ink, and that’s called drypoint. There’s a bunch of different techniques, but essentially they involve making lines in the print or making tone on the print. And the way you make tone is with acid. There has to be direct contact with the acid and the copper plate. Essentially, acid bites into the plate and leaves a tone. And you control that in various ways. I can paint the acid on. We can mask out areas, and then dip the entire plate in acid, and leave it for a certain amount of time, and then take it out, and repeat the process again and again until we get increasingly dark tones. When it comes to wiping the plate, he can mix the ink more strongly or weakly, and mix mediums into it, and control the color that way. And eventually, it seems we’ve always ended up with six plates, each one a different color. Or sometimes more than one color on each plate, so that there can be up to nine colors. And successively, we run these plates through the press on the same sheet of paper. They all add up and mix with each other to a full-color image. It’s a color separation process, which is similar to what they use in modern printing when they print a color photograph or something like that in the newspaper. But it’s all done by hand. There’s no photographic means involved. Everything is done the way it would have been done pre-photography, you know.

Walton Ford at work on Compromised (2002–03) with printmaker Peter Pettengill at Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, New Hampshire, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: What’s the story behind the print we’ve filmed you making?

FORD: The print is called Compromised. It shows two ibises, which are wading birds. One of them is called the sacred ibis and it lives along the Nile, or it used to. And then there’s one called a glossy ibis, which is a bird that lives in Europe and America. So, they’re entwined with each other, locked in an embrace, which is partly sexual and partly combative. They seem like they’re having sex and also fighting. And they’re in an Egyptian landscape. So, the glossy and the sacred are fighting. The sacred and the profane are locked in battle in this image. But they can’t get away from each other; there’s an attraction and a repulsion.

There’s this guy, Anthony Alexander Kingslake, who wrote a book called Eothen, which is about his travels in Egypt. And he talks about crossing into the Ottoman Empire and suddenly becoming compromised—which meant that you were in contact with people that were carrying the plague. And you were in quarantine the minute you entered the Ottoman Empire. And so, before you did it, you had to make all your preparations or else you would be stuck in quarantine for fourteen days. If you’d left one thing behind, you’d have to wait fourteen days to go back. So, it was like this way of leaving Christendom, as he put it, and entering the Ottoman Empire was compromising yourself, compromising your own health.

And I felt it was just like John Ashcroft and the rest of those guys; it seemed like what’s going on in the U.S. today. There’s this idea that “Either you’re for us or against us.” Either you’re compromised or you’re not. Either you’re infected or you’re not. There’s no room for middle ground now. It’s like getting the plague; you can’t have sympathy. You can’t try to understand the other side’s point of view at all—otherwise you’re compromised. “You will be carefully shot and carelessly buried if you break the rules of quarantine.” That was what Anthony Alexander Kingslake wrote about crossing those lines of contamination back then. And it increasingly feels like that would happen now with the new plague, which is just basically our complete terror and fear of what we don’t understand.

ART21: The work acts as political commentary?

FORD: Yes, based on some nineteenth-century colonial piece of writing that ties the whole together. That’s the way that I use a natural history image. I use a source that comes from the period that suits the natural history image, like this Kingslake book called Eothen, which is a beautiful book. And I try to bring it up to date and think about how it affects the way we think today and how similar the nineteenth century is to now. That moment of empire is almost the same. That moment of fear and first contact and misunderstanding and misapprehension is exactly what we’re going through right now. And we haven’t seemed to figure anything more or less out since then. You still feel like you would be carefully shot and carelessly buried if you made the wrong move.

It just felt applicable, you know. Sometimes the text seems to fit the image, and you get it all at once. Some of these images, like Compromised, that seem the most evocative, were started even before 9/11. That’s the weird thing. It was stuff I was already thinking about.

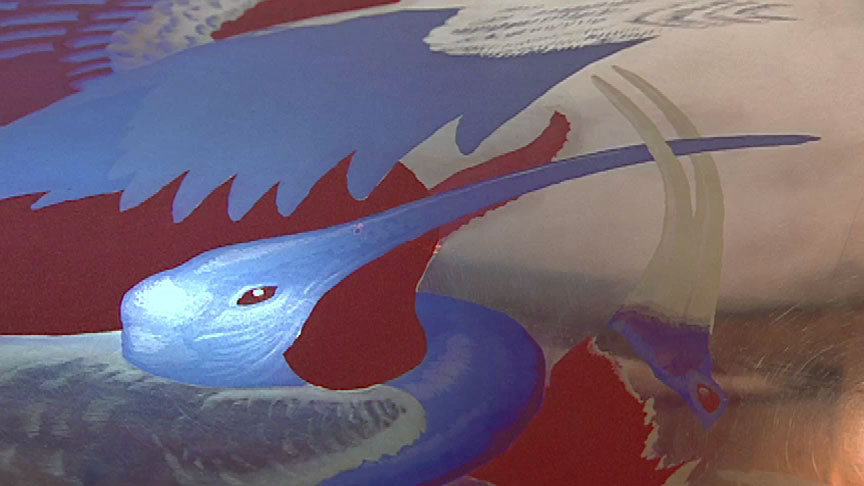

Inked copper plate for Compromised (2002–03) at Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, New Hampshire, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Are explorers always negative figures in your work?

FORD: Well, except for Mary Kingsley—oh, man!

ART21: What about Mary Kingsley?

FORD: Mary Kingsley . . . I haven’t made any art about her yet because I’m just reading her stuff now. She was a Victorian woman. There won’t be any art to back it up, but it’s one of the greatest stories. She took care of her parents until she was thirty years old. And was brilliant: she taught herself Latin and astronomy and geology, and she read every book in her father’s library. Yet she was a charwoman, essentially. She changed bedpans for her sick mother her whole life. And spoke “’enry ’iggins.” She couldn’t pronounce her h’s, even though she could speak Latin and Greek—amazing!

And when her parents died, they left her a small fortune. And she had all this time on her hands and went to Africa. She went to West Africa, and she went places that no white person had ever been. And she studied what she called “fetish.” She studied African religion with real compassion and with an attempt to understand—with very little judgment, based on the time. She was a product of the colonial thing and felt that the white man could be an agent for good in those regions. But still, she really kept her eyes open. She’s a really interesting woman. She discovered a whole bunch of fish that had never been discovered, and plants—things like that—and also wrote down a lot about West African religion. And she spoke out against King Leopold. And died in South Africa, nursing Boer prisoners of war, or something like that.

ART21: What makes her so noteworthy?

FORD: Well, she and Richard Burton are the only two people I’ve read about in that period of time that actually took the trouble to learn about the cultures they were taking over, or subjugating, or whatever. She had no agenda at all. She wasn’t there as part of the government or anything. So, she just went because she was curious, because she was slightly suicidal. Actually, she was unmarried and unhappy and so brilliant and so frustrated that she threw herself into the most dangerous part on the map she could find. Almost like, “I don’t care if I ever come home. I have nothing really to live for.” So, she went, and when she came back, she wrote it all down—an incredible prose stylist, funny as hell. And she ended up with a bestseller and was celebrated on the lecture circuit. But she was criticized for her way of speaking, and she said she was concentrating so hard on trying to pronounce her h’s during her lectures that she would ignore syntax. You know, I mean, she was an amazing woman.

ART21: So, she might end up in your work some day?

FORD: Oh, I’ve got to make art about her. There are just already so many stories! I’m just reading her stuff now. So, I’ve got to figure it out, but I can’t wait to make some pictures about her. She’s going to be kind of a major one, I think.

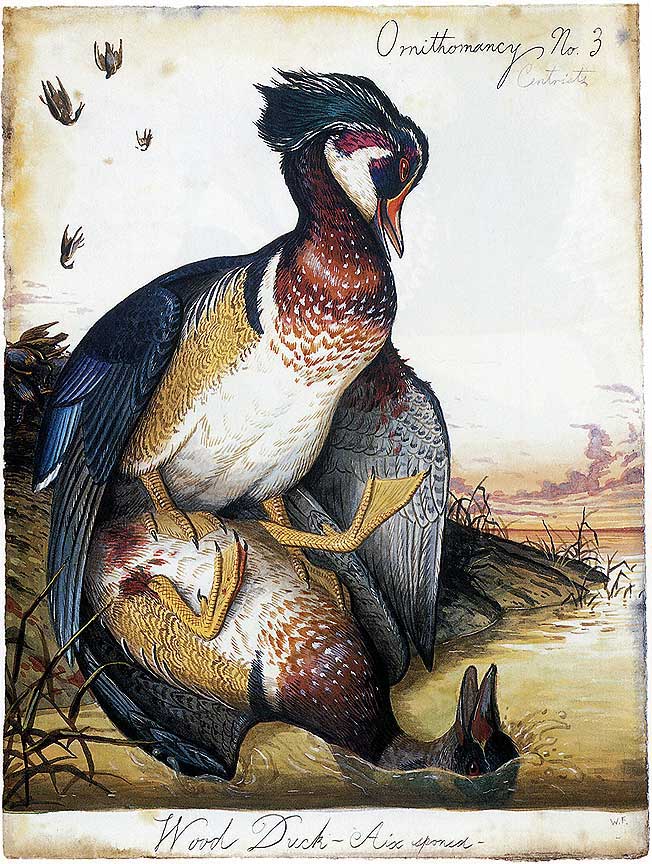

Walton Ford. Ornithomancy No. 3, 2000. Watercolor, gouache, ink and pencil on paper; 26 × 19 inches. Collection of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. Given in memory of John Stuart Fallow, Jr., Class of 1948, by Laura-Lee Whittier Woods. Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York.

ART21: Can you talk a little about your use of watercolor? It’s such a specific medium.

FORD: Part of the reason I got interested in using watercolor is that I was interested in painting things that looked like Audubons. They were like fake Audubons, but I twisted the subject matter a bit, and got inside his head, and tried to paint as if it was really his tortured soul portrayed. As if his hand betrayed him, and he painted what he didn’t want to expose about himself. And it was very important to me to make them look like Audubons, to make them look like they were a hundred years old—like he painted them but that they escaped out of him. Almost like A Picture of Dorian Gray, but a natural history image.

And once I was sort of finished with that, I realized that I sort of did those for my own amusement. And I was doing bigger oil paintings; I was doing constructions at that time. I was doing all kinds of stuff, trying to find my way. You go through these periods in your artistic evolution where you’re trying a bunch of different things out. And that was just one of the things I was trying out at that time. And I felt like it was more successful than most of the other things I attempted to do, partly because I had all these years of drawing, since I was a little kid. So, they were more convincing, right off the bat.

The other aspect I realized is that Audubon painted birds life-size. The birds were quite small, and the largest image he’d have to paint would be thirty by forty inches, or something like that. But I realized if I was going to paint something like a tiger, and I painted it life-size—if I painted it in that mode, it would suddenly become an object that hadn’t existed before. These things were done on the fly, in the field. You’d shoot a specimen, if you were Audubon or somebody, and you’d lay it out, and draw it, and watercolor it, and put it in a folio, and save it for later, when you published a book about the flora and fauna of wherever you were. So, for me, to suddenly make an elephant life-size or a tiger life-size—to make it in the mode of the notebook style and to imply that it was done from a dead specimen or done from life in the field—was just this odd conceptual object to make. It didn’t make any sense anymore. It starts to break down as a logical thing. And it began to get very exciting because I realized I was making something that nobody had ever made before. And that’s always a nice place to be as an artist, even when you’re working in such a traditional way.