Interview

Building Surfaces

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Time. © Art21, Inc. 2003

Artist Vija Celmins discusses her methodology, inspiration, and the materiality of her work.

ART21: Is there a way to describe how your work led from one way of working into the next?

CELMINS: Most of the changes in the work occur when I have had some kind of an experience that has been like a little awakening experience—usually out in life, and I’ve forgotten all about it—and then somehow it creeps into the work. I don’t know how to say that. You know, I think actually the night skies came out of the pencil—pushing the pencil so hard and getting in love with the black. The ocean came from (maybe) walking my dog on the beach all the time and beginning to think of this giant surface. And thinking about my own surfaces on the work. The desert—I used to roam around.

They come out of life, you know; they come out of poking around my own life. Like, when I picked those set of rocks in New Mexico, it never even occurred to me. I had them in the back of the car, and I put them out on the table, and I just had this instinctive desire to make them myself, as if I was maybe a creator myself. To make them myself, to see how close I could get, like a test or something, like a discipline. And then they became other things as I worked on them. So, I don’t know, but I’m obviously always picking up stuff, so—it’s very sculptural stuff. Look at this. That’s enough, for goodness sake; you’re making me, now, very self-conscious.

ART21: Explain why you’re preparing the surface this way. What is it about this preparation?

CELMINS: I start putting coats on the canvas. Just to get to know it and to begin to fill the canvas, building a relationship with it. I kind of like the idea of laying a field out. Then, many times I begin working with an image already on it. This time I thought I would build more of a feel, a feel that begins to fill up some of the grain of the canvas itself, so that there’s a kind of a semi-smooth, semi-rough surface. So, I put on a coat, and with each coat I try a slightly different color. Another layer. And I take it off because I don’t really like strokes at this time. I can’t really tell you why, but I’m not into strokes at this time. I have been into strokes in the past.

I put on an image, and I sand it lightly off to sort of push it back into nothingness, and I paint it again. This is a history of my working on this surface. It’s very (sort of) childlike, maybe, or a little dopey, maybe. But it’s a kind of a way of making the work dense by having many, many little layers on it. So, this is nothing; I’m just wiping this off, letting see what’s coming out, knocking down the top ridges. Making a mess in my studio. Getting a little work out.

Vija Celmins. Untitled #13, 1996. Charcoal on paper, 17 × 22 inches. The Edward R. Broida Collection.

Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

ART21: Is part of this that the paint will sit differently?

CELMINS: Well, I mean, what happens is that the first layers of paint soak in and kind of become one with the material, and now they’re beginning to sit on top, like little ice forming on the surface. It’s really bumpy. It makes a very frontal, flat kind of a field on which events can happen. And I tend to leave the edges kind of rough, so you have a feeling, so you really see the structure. You see the stretcher, the side of the stretcher, the work on the stretcher, the graininess of the material. And you see that it’s been patted out and considered already from the beginning. Like, there’s a little field that’s been built up, that’s quite smooth—not totally smooth but quite smooth. That’s what I’ve been doing. That’s what I’m doing on this one.

For me, this part is interesting ’cause this is the part where I’m, like, building, you know? I’m building the work from the get-go, like, from the beginning. You know, I’m building a surface, building a kind of a mass that’s gonna sit there. I don’t know—it does sound a little strange when you say it right out, but this is all part of the work. In fact, I often now talk about building a painting instead of painting a painting. Like, I’m building a painting; I’m making a structure that’s a painting cause it’s a two-dimensional object—it relates to the wall—but that it also projects out. So, this is part of the beginning of the work.

ART21: Could you explain how you work with your source images—that the photograph is not an image that you’re copying, but rather it’s an image that you’re using in some way to create the painting?

CELMINS: Well, I don’t really say using, either. I was trying to think of the word. I usually talk about it like I’m re-describing the image, you know, through my body and through my sensibility—through everything I know, really, about how to make a painting. I’m making a painting. I’m not really copying an image. You know, when I did all the early still lifes—I looked at the lamp, I copied the image. But when you’re working with an image, it comes from another world, you know? It comes from three-dimensional worlds. So, this is an image in a three-dimensional world, but actually the work does not look . . . I don’t know how I could say it.

For me, it sort of focuses my activity but frees up something else. I was trying to say, maybe, it’s a touch that is then allowed to be. I was gonna say gesture, but I’ve kind of removed the gesture from the painting. But I still have a touch through which you (sort of) can experience the work. It’s hard to talk about painting. I mean, it’s hard for me to talk about the painting because I don’t know a lot about it. You know, in a way I don’t know that much about it. It isn’t like I’m totally in control of everything. But I have this little area now that’s beginning to work better on the painting, which makes me happier. But I still don’t know whether I’m gonna be able to continue with these, this little color thing here. It’s a little dull, maybe.

Vija Celmins. Ocean Surface Wood Engraving 2000, 2000-2001. Wood engraving on Zerkall paper, 20 3/4 × 17 1/4 inches. Edition of 75, AP of 16. Published by the Grenfell Press, New York . Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

ART21: Something in what you’re saying reminds me of Cézanne and what he was trying to do.

CELMINS: Well, Cézanne, you know—Cézanne has inspired so many painters. I mean, when you look at this, I don’t think you would probably think of Cézanne. Believe me. I mean, the thing that I think I got from Cézanne and looking at Cézanne—which took me years—is sort of a really gutsy relationship between the image and the plain flat object. He has such a wonderful way of pointing that out to you in every stroke. And also the fact—which I think was a great part of the twentieth century—that this is an invented thing, you know? That it’s not, like, a copy of nature or a copy of a photograph. It’s an invented thing that you have in front of you, you know? So, I think I kind of have that in me somewhere, this relationship.

I think it sort of shows up in different parts of my work, and sometimes I lose it a little bit, and sometimes it’s more apparent. I mean, Cézanne lived in France. He had this fabulous country and light. I’m a very studio-oriented artist, you know? Some artists now—the street is their subject; they love it. I love the street too, but my whole work is really very studio-oriented. This is the place where everything is allowed to happen. I bring in things like my shells and rocks from the outside—always thinking that maybe I could somehow use some part of them—but it’s very hard for me to work directly now. It’s like, I work directly here, but it’s very hard for me to look at something. Not hard in terms of that I can’t do it, but intellectually it’s hard for me to do. I see no reason for it. There are a lot of things that I don’t think I can do.

I make a sort of a distant-and-close object that is a painting—that’s how I think of it—and sometimes a very strange-looking painting. Like I think, for instance, that’s a pretty strange-looking painting over there [The River’s Galaxy]. It’s kind of an enigmatic spatial painting I’ve been more interested in lately—meaning, maybe, the last two or three years—a more ambiguous space, flat: a space that’s harder to place yourself in.

ART21: Is the darkness of the image an inherent quality of the flatness?

CELMINS: These dark paintings came out of me making those graphite drawings darker and darker—those drawings that I did in the late ’80s. And I thought, “This pencil, which is graphite—they just can’t hold anymore.” I wanted more out of them, and I didn’t think they [could] carry more, so I just sort of slipped into this image. I do like kind of impossible images—I mean, images that are hard to pin down, that aren’t like a tabletop and an apple, but images that are really almost like mind images. Images that are space, but they’re hard to grasp. But then, they’re very graspable here. I mean, I make them accessible through another way, through manipulating the paint.

I did a whole series of black works—I don’t know now—twenty, thirty works. I thought it was quite difficult to make a black painting work because it has such an incredibly strong silhouette, you know? But it did a series of things. It invited you closer and closer to the work. I don’t know what I think about that yet, but I thought it was sort of an interesting phenomena that happened. And I think at a certain point I thought I didn’t want to do it. I’d actually done a reverse galaxy a long time ago, maybe twenty years ago in a print. And I thought I would turn the tables on the image and have the reverse image and lighten up the painting—kind of a totally different kind of space. So, I did it, and I’m interested in it. I think this painting looks so strange, and it looks like a piece of concrete. And when you get very close to it, you begin to think you’re hallucinating a little bit. It changes color and tone, depending on where it is. I began to think that those are interesting qualities that I wanted to try.

So, I kept this painting. But I’ve been working on this thing for a year. I have to try to come to terms with it. I’ve had it [for] a year, off, where I was doing all kinds of other things. But I like being back in the studio, you know, working with this strange tedious surface.

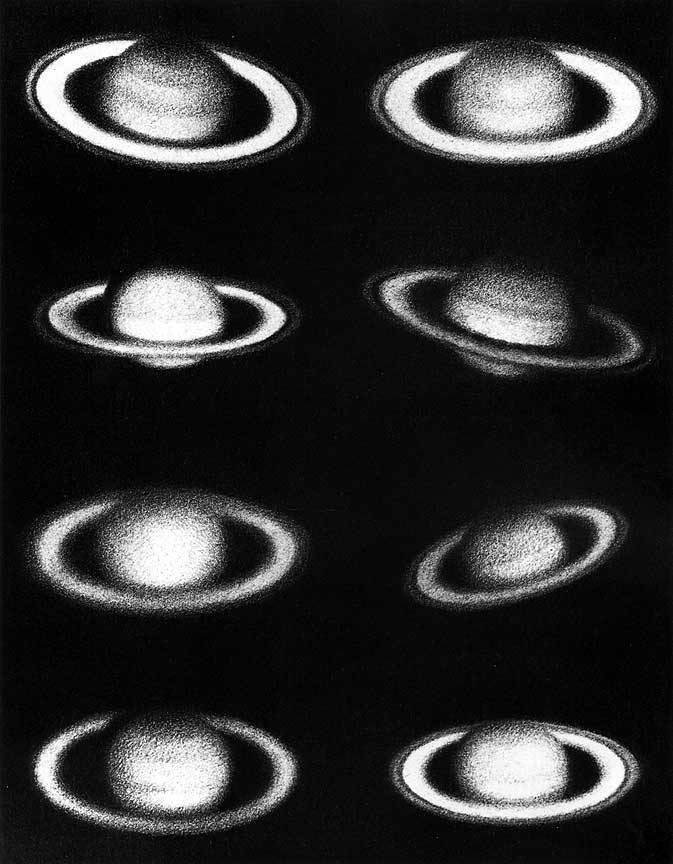

Vija Celmins. Drawing, Saturn, 1982. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper, 14 × 11 inches. Collection of Paine Webber Group Inc., New York. Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

ART21: What causes you to take a little of that dark turquoise or that ochre? What’s behind that?

CELMINS: I don’t know—intuition? This needs a little this . . . this needs a little this . . . this needs a little this. I don’t question it; I follow my intuition. That’s what I do. I have been putting quite a lot of cerulean in the black. It makes the black have a tiny bit more atmosphere. Makes it a little bit cooler, makes it a little bit chalkier. I kind of wanted to do that.

Each one is a little bit different. Even though I’ve been sort of obsessed with this image that describes a space, I don’t really have an agenda here, where I line them up and do it one way. Each one develops how it wants to develop.

Ugh. I just did the wrong thing. I just put in this little thing, and it makes this little pattern. This talking is too much. Now, look, I’ve ruined my painting. Or maybe not—eek!