Interview

Childhood and Influences

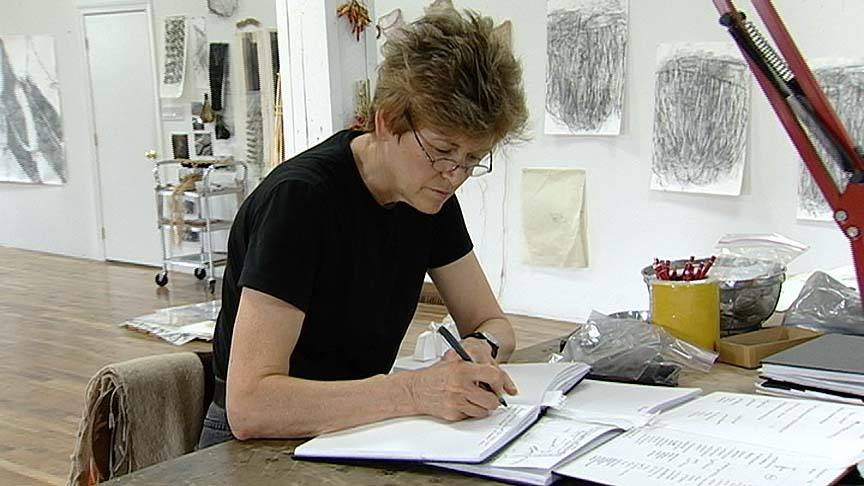

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Ecology. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

Ursula von Rydingsvard discusses how she came to live in the United States, and the ways in which her earliest memories inform her work.

ART21: When did you first come to the United States?

VON RYDINGSVARD: I came to this country in 1950, in December, and I started school right away. They put me in fourth grade. I don’t quite know why, because I was only eight years old. I was also in fourth again the following year, but I learned English in about six months. I had a wonderful teacher, Miss McNamara, who made a fuss over my being there—because in a place like Plainville, Connecticut, where we settled and lived, there were not many people that came from another country. So, I was exotic.

The clothing that I wore was truly exotic: I still had pants that flared out, tight at the bottom and flared. I’m not quite sure how to describe them, but they were made from U.S. army blankets, which were rationed out to us in the camps. So, I was wearing those with some sort of a pathetic top. I truly was exotic—to the extent where, on Valentine’s Day, my teacher bought me this beautiful red velvet dress with all this white lace, a big collar, and little puffy sleeves. It was so beautiful, but I could not get myself to wear it. I gave it away as a gift; I don’t even know to whom. We needed a gift at school to give to someone else, and since we were too poor for me to be able to do that, I just gave away the dress. It was so girly and so sweet that I couldn’t quite make the transition from these great blanket pantaloons to this dress, that quickly.

ART21: Where were you born?

VON RYDINGSVARD: I was born in 1942 in a beautiful little town called Deensen, in Germany. Between 1942 and ’45, my father was a forced laborer on farms. When the war ended, my father saw no opportunities. He decided to try to go to America—a huge wish, given that he had seven children. You could go alone as a single man, but it was much more difficult to go as a member of a family of nine. Both he and my mother made the decision to go through the postwar refugee camps for Polish people who didn’t go back to Poland. So, we went through eight camps, working our way north. From Bremerhaven, the northernmost port in Germany, we took a ship to the United States. It was a military ship—that fed us divine food. We couldn’t believe what we were being fed, but we were so seasick that we couldn’t appreciate it. We came to the port of New York City. We saw the Statue of Liberty, because everybody was called on board to see that. I think we got off at one of the piers on the west side of Manhattan.

Ursula von Rydingsvard. Dla Gienka (For Gene), 1991-93. Cedar and graphite, 88 × 53 1/4 × 31 3/4 inches. © Ursula von Rydingsvard. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong, New York.

ART21: Did your family have to work in the camp?

VON RYDINGSVARD: In Deensen, my father farmed the land, and they wanted my mother to do that, too. But at that time, she had a newborn baby, a two-year-old, a four-year-old, a six-year-old, an eight-year-old, and so on, so it was not something that she could do. She was able to wrench her way out of it, in good part because my father was such a spectacular worker. When he would use the scythe to take the wheat down, they would say to him, “Ignaz, seven men couldn’t what you’ve done. In a day, seven men couldn’t do this much work!”

The camps had a whole other order. Basically, none of the men worked. There were no jobs. Periodically they were all sent to some factory for three weeks, or some such thing. And I remember one of the factories actually exploding. The Marshall Plan that was set up by the United States government helped us enormously. It was specifically made for the post-World War II refugees, to enable them to survive. I think the men were the most troubled of the lot. The women continued to raise their children as they normally would. They were under circumstances that were extraordinarily difficult, but they were paying attention to the children. The men would play cards, or they’d drink a lot. And what they would drink was just terribly cheap, lousy stuff that they would manage to make on their own, because there was really nothing for them to do. The women were more religious than the men. They allowed the Catholic Church to guide them more stringently. So, the Catholic Church was our law. There were no police, nothing to organize people’s lives.

Periodically, if we stayed again in a camp for a longer period of time, there were former teachers that came to teach. They just organized this amongst themselves, which I think was extraordinarily helpful for the children. I remember those classes very well. And I remember how serious those teachers were. They were all male teachers that were extraordinarily strict. I was the conscientious type. So, if a child didn’t do his lesson properly, I would be the one that would have to whip the kid with a leather belt. And the sound had to be a certain kind of sound, when you whipped the kid, in order to make that whipping credible. So, I had to muster up everything I could. I think that a lot of Europe had that kind of teaching, though. I don’t think it was that unusual.

ART21: Why didn’t the teacher just give the beating himself?

VON RYDINGSVARD: It’s about the teacher giving me the power to control this other child, and showing it in public, in front of the entire class. You know: he who learns will be in control, and he who doesn’t learn will be the victim.

ART21: How old were you when this was happening?

VON RYDINGSVARD: I was in second grade.

ART21: It’s so shocking.

VON RYDINGSVARD: I think it wouldn’t have occurred to anybody that this was something out of the ordinary. The children were so used to seeing it, and the adults as well. I don’t think that the teaching was that different in other parts of Europe, whether you went through the war or not.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Ecology. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

ART21: What else do you remember from this time?

VON RYDINGSVARD: Paper was very hard to come by, but I actually got a little pad with lines on it and unbleached paper. When you wrote in that book, you considered with such care. It needed to be absolutely perfect. If you made a mistake—there were no erasers—you had to wet your fingertip and rub it in such a way that you didn’t rub through. And you had to rub it in a way so that it wouldn’t leave this awful mark behind, you know. Sometimes we would get books that we would share. And all of these things felt very privileged and wonderful, you know—like they belonged to another world.

ART21: Do these early experiences affect your work in any way?

VON RYDINGSVARD: If I were to point to something from the camps that one can see most directly in my work, it is that we stayed in barracks—with raw wooden floors, walls, and ceilings. I have a feeling that that fed into my working with wood. And the first time I ever saw Poland, all of the villages, all the homes there, were made of wood. There were stacks of wood, doors and troughs of wood. Wood was the building material. So, it’s somewhere in my blood, and I’m dipping into that source. The way in which I manipulate the cedar is very important to me, but I have a feeling that I even learned from things that I never saw. Working with it and looking at it feels familiar.

I actually visited the home where I was born, and it is made out of wood at the top. The bottom is made out of those dark beams with white plaster in between the beams. There was a basement in which the animals and the beets and the potatoes were kept. That was wooden, too.

ART21: Do your memories get absorbed into the work?

VON RYDINGSVARD: I remember sitting on steps and having on something like a nightgown. This nightgown was made of a raw linen that was quite stiff, and it folded in ways that had almost mountainous landscapes to it—a kind of erect landscape that made all kinds of indentations and crevices, little hilltops, and so on. And I just remember feeling it on my body—the harshness of it and, at the same time, the softness of the parts that were more worn down. And I remember the sun hitting those structures on my body. That’s a memory that has vagueness in it, but I’ve dipped into it a lot.

ART21: Given where you came from, it’s kind of remarkable where you’ve ended up.

VON RYDINGSVARD: Obviously, it was impossible for me to consciously think that I was going to be an artist, because I’d never heard of anything like an artist until I came to the United States. I just know that I feel like I drank from the world through visual means—that that was a huge source of the information by which I lived. My home was one in which words were not used very often. With my parents, the only words that were exchanged were in connection with assigning labor: “This is what you have to do” and “This is what has to be done.” So, words were very, very sparse. And in fact, anybody that used too many words was automatically suspect.