Interview

Storytelling—Characters and Colors

Trenton Doyle Hancock at James Cohan Gallery, New York, NY, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Artist Trenton Doyle Hancock discusses his story of the Mounds as it’s told through his paintings.

ART21: Your paintings and installations are but moments in the larger narrative that is the story of the Mounds. Can you summarize that story?

HANCOCK: Okay, but first I should explain a little bit about what Mounds are. Mounds are these half-human, half-plant mutants that came to life about fifty thousand years ago, when an ape-man masturbated in a field of flowers, and up sprang these creatures, and they’re called Mounds. Since then, many of them have died off for various reasons, but the main cause of death of Mounds is the premature death caused by creatures called Vegans who are evil creatures who can’t stand Mounds at all. And over the past few years, I have worked through the first major chapter about Mounds, and it’s called The Life and Death of Number 1. And Number 1, The Legend, is named that because he was the very first Mound to exist. And he’s the oldest Mound. And the Vegans hate him with all of their being, and so it was their mission to take him out. And so, the Vegans plotted, and they achieved their goal.

There are some protectors that are supposed to protect these creatures, but the one main protector was busy at the time, so he couldn’t come to the Mounds’ aid in time. His name is Torpedo Boy. Torpedo Boy is kind of my alter ego. He’s who you see sitting before you right now, in the yellow shirt and pink T. And he’s super strong except he has an inflated ego. And his pride and all of his other human emotions get in the way of him performing his duties. So, he’s very limited by his flesh.

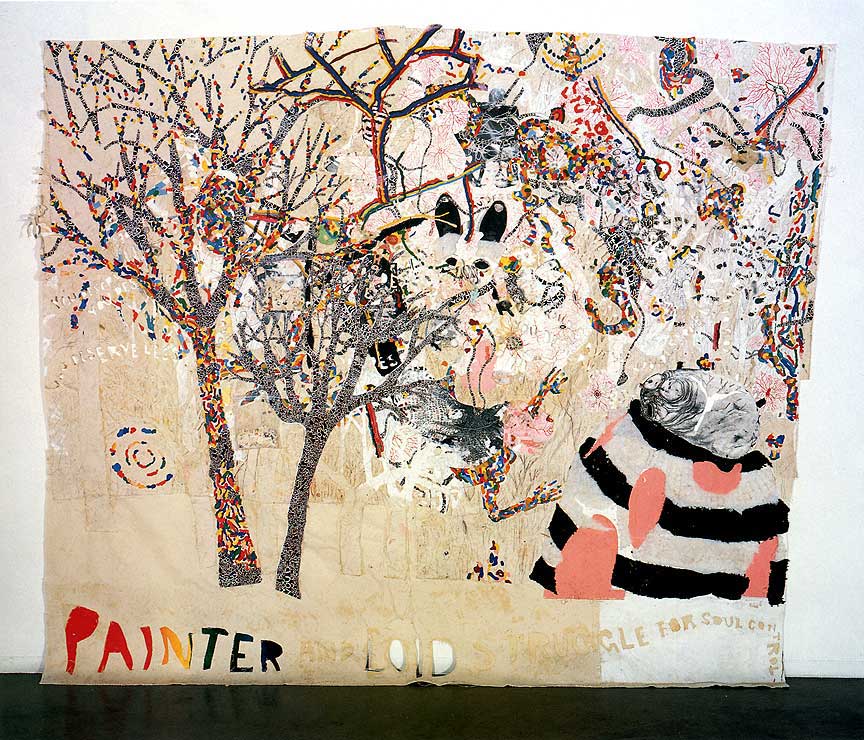

Before there was Torpedo Boy, there were Painter and Loid. Painter is a spirit energy, who is kind of a mothering type of an energy, who is all about color. Any time you see colors within the paintings—that’s as a result of Painter’s presence. And the other energy is called Loid. Loid is kind of a father type of an energy, and he takes care of any time there are words within the paintings—that’s his doing. And he’s also all about black and white; there’s no in-between. So, when you see black and white or words within paintings, it’s Loid. And Painter is the color. So, all of these characters are just ways for me to break my aesthetics down into something that I can use in my palette.

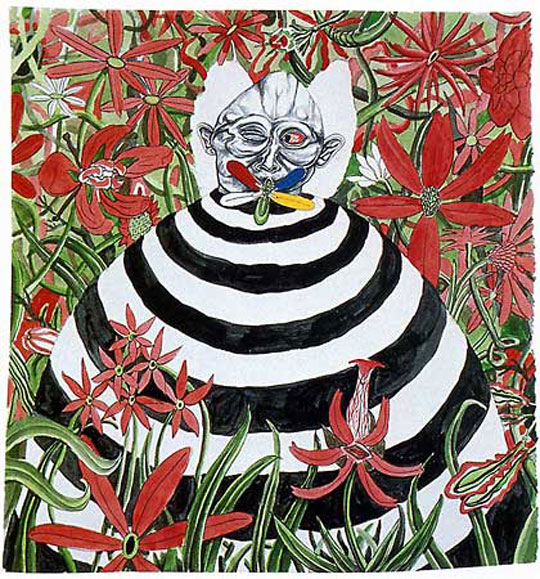

Trenton Doyle Hancock. I See Things, 2002. Graphite and acrylic on paper; 11 1/4 × 11 inches. Collection of Stuart Ginsberg, Chappaqua, New York. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery, New York and Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas.

ART21: When did you start to develop the story of the Mounds and the individual characters? How did they get their names?

HANCOCK: I’ll start with the Mounds. The Mounds, or the name of the Mounds, kind of came from a series of drawings that I was doing when I was an undergraduate. That was the name I would give to groups of things. It’s like a mound of information. And I had other friends that also did drawings that related to that same kind of a thing. So, it was something I’ve always done; like, I like to group lots of things on one page. But also a mound is a way that I organize information. Like, things pop up around anywhere I move; these mounds seem to move with me. In my car, there’s like a pile of things—that’s a mound. In my studio, there are piles of things all over the place, and I pick from these piles—those are my traveling mounds. A mound is a way to describe how I organize things.

Torpedo Boy has always been with me, more or less in the form that you see him now. He’s a super hero; he can fly, he can lift things. I created him when I was, I’d say, in the fourth grade. And he’s pretty much the same as he is now, except now he’s a lot more flawed, and his uniform is yellow when it used to be white. And that’s pretty much the only difference.

Painter is—well, I’ve always been drawn to color, but it always has to be necessary. Color has to have some sort of a meaning if I’m going to use it. It’s hard for me to just choose random color and use that as information because I start to feel disconnected from it. So, especially lately in the work, every color—every time it appears, it’s there for a specific reason. And if there’s no reason for color to be there, then the piece will probably just end up being black and white, which I’m perfectly okay with. And that’s where Painter comes from.

And then Loid is just this love that I have with both the lyrical nature of the spoken word and also the way language looks when it’s written. So, Loid operates in both this space where he can convey something to you and you fully understand it, or it can totally be abstract, which is what language has the capability of doing, either including or excluding you. And that’s what Loid is all about.

ART21: Can you talk a little more about how you use color to drive the narrative aspect of your work?

HANCOCK: One of the colors that pops up most often in my palette is pink. It’s a color I’ve always been drawn to because it’s so loaded with meaning, contradictory meanings. It can either be naughty, or it can simply be the color of our skin. It’s the color of our muscle—like, if you peel the skin away, you know it’s pink under there! It’s also the color of innocence—like, in a little child’s room, you see pink. It operates on so many different levels that it had no choice but to keep coming back up in the work.

Torpedo Boy’s uniform is pink and yellow, and that’s one of the most obnoxious color combinations I could think of. Pink and yellow—it’s very loud, and that’s kind of what Torpedo Boy is all about. His ego is his force field. That’s just how he takes on the world. And I thought he needed to have a uniform that reflected what he was all about. So, pink and yellow became his color combination.

The Mounds, they also have pink within, but on the outside they’re all black and white. And I’d say the white and the black first came from a lot of drawings that I was doing that had to do with identity politics and race and things. And I was doing a lot of things that became really literal to me, in approaching that kind of subject matter. You know, the fact that I’m a black artist, and there was something at one point that I wanted to explore. And I did that thing to a point, and I just got really bored with how things were turning out. It’s like everything was kind of given already, and it was just something that I already knew in my heart—all of these issues—and I was very comfortable with who I was anyway. It wasn’t something I wanted to explore any deeper.

But the black and white motif—I wanted to retain that and make it something that became a little bit more universal. So, the black and the white morphed from that kind of subject matter into something that I could use as a module. And these stripes became what we now come to know as the Mounds. And the pink is there because these Mounds are wounded characters. You start to see underneath these sores that start to emerge and interrupt the black and white bands. That’s what the pink is. So, the Mounds ended up being pink, black, and white.

Painter is, in a way, synonymous with color. So, it would only make sense that her energy would be all of the colors, a rainbow of colors. Painter, with her array of colors, with her spectrum—she represents hope and tolerance within the universe. Whenever bad things happen, she can come in and present us with a layer of color over the top of things to, I don’t know, just to give you a little something else to look for or hope for. I think that’s where the tolerance comes in the work. You can tolerate the bad stuff because of that little bit of color that you’re given. It’s kind of like: “The spoon full of sugar helps the medicine go down.”

And Loid is devoid of emotion. There’s no real range, there’s no rainbow: it’s either black or it’s white. It’s either all the colors, which kind of negate each other, or it’s no color at all.

Trenton Doyle Hancock. Painter and Loid Struggle for Soul Control, 2001. Mixed media on canvas; 103 × 119 inches. Collection of Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas, Austin, Texas. Courtesy of James Cohan Gallery, New York and Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas.

ART21: You describe Torpedo Boy as an alter ego. What’s your vision of yourself in your work? How do the characters relate to your identity?

HANCOCK: I see each character as a separate part of me. I can separate one aspect of my being out, and then put it in front of me, and then look at it. And it’s kind of like all of these things are inside me at once, battling each other. And at certain points, one is dominant. Like, at one point I may be Torpedo Boy: I might have the biggest ego ever. And then at another point, I could be one of the Mounds: I could be this stationary object who’s kind of pathetic and a bit stubborn and kind of sad. And then at another time, I might be one of the Vegans who’s self-righteous and looks to make others around him or her like him. So, it’s up to each of those other parts of myself to balance that dominant side out and make it come down in size.

ART21: And yet, while Torpedo Boy is your artistic persona, he also has a religious or mythical dimension. Are biblical narratives a big influence on your work?

HANCOCK: I grew up in a very religious family. My stepfather is a Baptist minister. There were several ministers in my family. My mom and all of her sisters, my grandmother—they are all very, very religious. We went to church at least two times a week. And you know, that’s just how I grew up, and it was a sense of community. The church was filled with beautiful stories and great music, and it was a very visceral type of experience. And that type of experience also spills over into how you live the rest of your life. You know, things were dealt with in those terms—like, it’s very, very old-fashioned, you know. Punishment meant a different thing than it means nowadays. Like, it was very, “If you don’t feel the punishment, then it doesn’t count.” So, it was that kind of a mentality. The idea of these beautiful stories—these archetypes of heroes going through toil and trouble and coming out all the better for it, or teaching us all a lesson not to go through, to take a different path—I wanted to incorporate that kind of thing into the way that I tell stories.

And also, a lot of it comes back to my mother. She is Painter and she is Loid, wrapped up into one. She is the smiling face of Painter. She is the color that you get from Painter, but at the same time she could be stern. When she put her foot down, when she spoke her word, you had to listen. And if you didn’t, she made, you know, sure that you listened the next time. So, she was also Loid. So, in a way, the mother and father energy in my universe are both my mother.

ART21: Are there any biblical stories that still resonate for you?

HANCOCK: There’s one particular Bible story that always stuck with me when I was a child, and I like to kind of relive it in my head, and that’s the story of Jonah and the whale. The idea of this prophet who kind of knew that he was a prophet—he knew that he had a calling, except he didn’t act on it, or he chose to deny it and choose another route. And God let him know: “I’m going to give you a chance to think about what you need to do with your life.” So, he had him be swallowed up by this whale, in which he had time to think about his plight, where he’s been and where he should be going. And he had to do it in the stinky belly of this whale. And I just thought that was a wonderful story, growing up. And I always wondered, “Well, is there water inside of a whale stomach? You know, does he have to swim around in there? What must it smell like, dead fish? The smell of dead fish—that must be horrible in there!” That stuck with me: always listen to what’s really your calling, what’s in your heart. And you know, it may sound corny or whatever, but those stories do actually mean a lot when you get down to the meat of the stories. They’re beautiful things that you can just kind of take along in your pocket and take out whenever you need them. Jonah and the whale was pretty cool.

Trenton Doyle Hancock in his Core Residency Program studio at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: And the story of the Mounds—you say it comes to you in flashes. It’s like your own personal calling.

HANCOCK: The story comes to me. I like to refer to it as visions. But when you break it down, you can actually break down a vision into a series of questions. Like, after I realized what Mounds were, I had a lot of questions for myself—“So, where do they come from? How tall are they? Do they eat?”—like, just all of these types of things. In asking a question, you can then have an epiphany because it’ll open up the floodgate to twenty new questions. And from there, you just keep going and it snowballs. And to me that’s what the vision is all about. It’s taking notice of things that are around you and then questioning them. And out of those questions will come answers but hopefully a lot more questions. And from there you can just keep your vision growing.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.