Interview

“It Came from Studio Floor”

Trenton Doyle Hancock in his Core Residency Program studio at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Trenton Doyle Hancock discusses his work’s relation to language and storytelling, and how he came to use of trash in his collaged pieces.

ART21: Why do you use trash in your work?

HANCOCK: I get a lot of inspiration from garbage that I find, whether it be tops that I pick up out of the bin at the laundromat or something that I saw on the side of the road and was so inspired that I had to stop the car and get it and put it in the trunk. There’s something about getting something that is free that is appealing to me, for one. But then, the things that people throw away—oftentimes they throw them away because they’re old. I see these objects that have this patina to them, that have this obvious history. It’s been loved and hated and loved again, and ultimately discarded. There are so many stories to be told within these objects. And oftentimes, once they’ve been thrown away and you find them in the garbage, they’re pale imitations of what they once were. And it’s just, sometimes, very intriguing and exciting to see what these objects have become. And so, I set them up and then make up my own stories about them.

ART21: When did you first start to use collage?

HANCOCK: When I was an undergraduate, I worked for the school paper, making cartoons. And that was a great thing for me to go through because I had to make images quick. I had to come up with pretty much a story on the spot, maybe dealing with a story that was given to me, but from that I just used it as a jumping off point to make these stories. But the drawings usually ended up being flat. And there came a point where I just got kind of bored making these flat drawings, so I started to experiment with collage and building up the surfaces of these drawings, sometimes very subtly, where you wouldn’t really know that, you know, something had been collaged on unless you investigated a little further. And then it got to the point where I had learned how to do that, and I just wanted to put something on that was a little dumber, like something that you knew was collaged on. And eventually collage just became something that was part of the process.

So, it went full circle, from something that was a pictorial space. These cartoons were all about good design: like, you knew what was happening, it was a quick read, and then you could go on. And then it went to something that was all about not being able to read it so fast. And now, it’s morphed into this thing that is a combination of the abstract things that I was doing and those cartoons that I wanted to do, and the cartoonist or the comic book artist that I wanted to be when I was a kid. All these things are coming together to form this new thing for me. I’d say, ultimately, I wanted drawing to be a lot harder for myself. It just seemed too easy to make a drawing. I wanted to remove the immediacy out of it, out of the process. And I think majoring as a printmaker when I was an undergraduate helped me learn how to do that. It gave me patience. It helped me to see steps into the future in terms of what a drawing could be, or in terms of creating an image. And ultimately, it just led to a much richer kind of an image, something that you can read from top to bottom, from back to front. And so now, those types of issues are just a given when I think about my work.

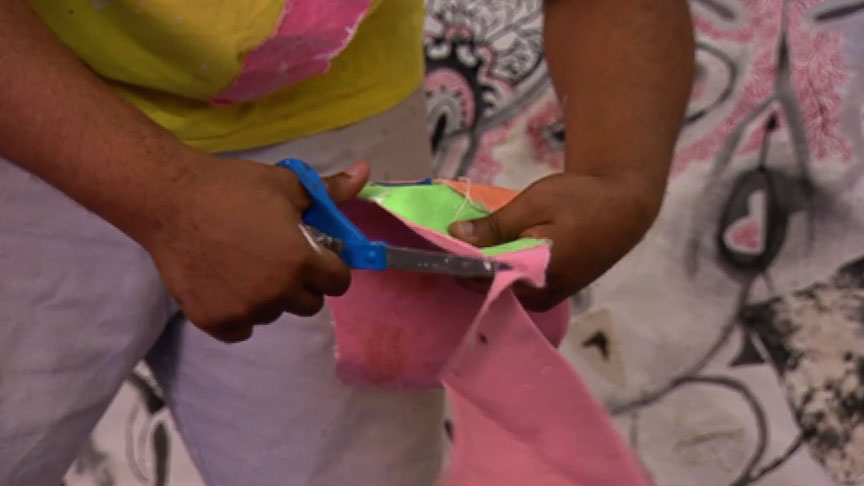

Trenton Doyle Hancock in his Core Residency Program studio at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: How does language factor into what you’re doing now?

HANCOCK: One of the bodies of work that I’m working on at the present moment is work based on my studio floor. I have all these piles of scraps that are pretty much remains of paintings that I cut up or set aside for the moment. And I have piles and piles of these little colorful scraps. And some of them are made out of felt, some of them have paint on them, some of them are paper. And what I wanted to do was make something out of all of that, because a lot of it has been sitting around for about three years, and I hadn’t done anything with it. So, I wanted to make a body of work that dealt with the things that I’m finding on my studio floor. So, there was that. And I started to glue all those pieces onto big bands of felt of all different types of colors, so they ended up looking like these giant rugs. And furthering that theme of the studio floor, I took the words studio floor and made all these anagrams out of that, out of those words. And I came up with about, I don’t know, fifty different anagrams and all of those, (LAUGHS) all of them led back into the story somehow. It was very strange. Like, the word loid appears in that anagram. The word tofu. It was so weird that I was, like, “Oh my goodness! Well, this is the next step.” So, at the same time as I have these giant goofy kind of abstract things hanging on the wall, I’m going to also have these tight pencil drawings that have the characters in there. And the characters will be having dialogues with each other, and it’ll be like a storyline, but everything coming out of their mouth will be one of those anagrams. So, they’ll be talking to each other, but it’ll be in this, I don’t know, baby talk or something, because it’ll just be: “Tofu rule.” Or, “Tofu is drool.” Or things like that.

ART21: How does this rug painting relate to the overall story of the Mounds?

HANCOCK: What these are, I’ve come to realize, are dream flashes, which are extended color flashes from Mounds. It’s just bursts of hope, and that’s what the Mounds are telling us here. This kind of thing happens all the time throughout the storyline. Like, Mounds only communicate in bursts of color and symbols. So, I mean, this is just one of the many bursts of color and symbols that they’ve sent. I like to think that those paintings are how this Mound here, who has passed on, is communicating with me after he’s gone. So, he’s sending these visions of hope, saying that, “I’m gone but I’m not forgotten” and that you know things will be okay. So, in a way, it’s like God’s promise with the rainbow after the flood—that this kind of thing will never happen again.

Trenton Doyle Hancock in his Core Residency Program studio at the Glassell School of Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Stories. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: What do you think the relationship is between the formal elements of your painting and the story you’re telling?

HANCOCK: I think one of the ways that the story has evolved—I’d say, over the past five years, when I actually started doing a lot of collage and building up of surfaces and tearing down of surfaces—is that I started to realize that the content of the stories that I was interested in had a lot to do with something being broken down or built up or something having to be rescued. Things decaying. So, I started to search for materials that spoke to that same kind of sensibility.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.