Interview

Chicago & City Planning

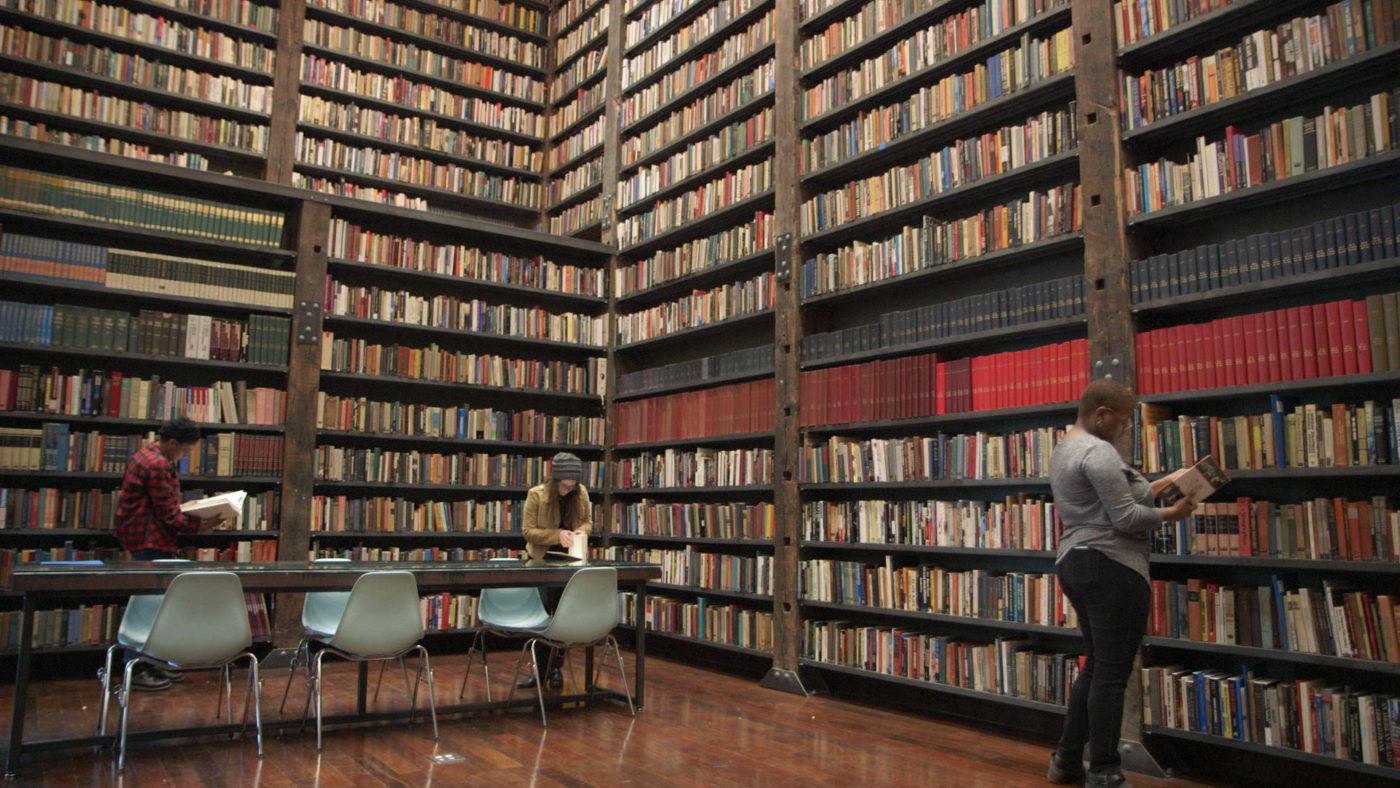

Production still from Theaster Gates's segment in Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

Theaster Gates talks about his childhood in Chicago, and shares how he describes his work as an artist, builder, and teacher.

ART21: What was it like for you growing up in Chicago?

GATES: It was a good boyhood, I did well in school. Like many, many young people I got bused out of the neighborhood and ended up going to a middle school that was on the North Side, called Reilly Elementary. From Reilly I went to a better high school, and it was there that I could start to see this divide between me and my peers—kids who stayed at the local elementary school and then went to the local middle school. These new cultural shifts were starting to happen to me and through me as a result of taking the bus up north every day, and being in this other culture where I was not the smartest kid in the class anymore. It was an interesting moment where there was this early shift that started to establish my life as slightly different from some of the people around me.

Production still from Theaster Gates’s segment in Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

ART21: How did school affect your decision to be an artist?

GATES: There’s this idea that there are forces in the world that are dangerous and violent and could take you off the path, and that those things are right next door. My mom would talk about that as a reality and as a metaphor. She would say, every day you’ve got to go to the bus stop and make decisions about what’s important. That idea of this hedge of protection, it was this constant knowing that if good things were going to happen in the world, they would because one had to make a significant effort to do the [right] thing. Bad things were all around, but to do the good thing would require some real forethought and girding. Especially as I got older, my friends who I grew up with were choosing other paths, and then I had to figure out what to do with those friendships. I love these guys, these are my homies. At the same time trying to love them, and also accept that the path that was being laid for me, or that I was laying for myself, was a little bit different. I was getting exposed to these things that were very different from what was immediately around me on the West Side.

There was that dynamic of people who were involved in the sophisticated world, not just the struggling crack-infested world—they were involved in these other worlds that were worldly and good and fashionable. I was like, wow, maybe these more sophisticated apertures could refocus my life, and that was very exciting.

ART21: So much of who you are is rooted in those experiences in Chicago.

GATES: By the time I finished high school I was clear about one thing: I would not be embarrassed about where I’m from, no matter how much these other worlds tried to share with me that where I was from was bad or different. I had already developed a kind of fortitude that what my mama and my daddy gave me at 701 North Harding was some good stuff, and I would find a way to carry that forward.

Production still from Theaster Gates’s segment in Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

ART21: How does that inform your art practice now?

GATES: There is this principle calling that feels like it’s about me putting things in the world. But what those things are aren’t necessarily always objects. They could be interruptions in the city. They could be new building structures. They could be the creation of a new platform, not-for-profit, or for-profit foundation that could support bodies of work over time. This is not new to art, but art in its modernistic tendencies and in its capitalistic pursuit want so badly for us to only focus the artist on the production of things.

ART21: Talk more about this combination of the city planner/artist.

GATES: One of the tricks that I’ve had to figure out in my head is [how] to describe to other people what I do. I say I wear three hats: I am an artist with a studio, I build these buildings, and I’m a professor at the University of Chicago. I don’t actually think about myself in three parts, I think about my whole self. My whole self makes things—I’m an artist and I make things. Sometimes those are things that we call art and other times they seem like other things. But in fact, I’m always making a pot, it just doesn’t always look like a pot.

There are times when I make an object out of flooring that is made for the wall. And then there are times that I make flooring that is flooring. Both of those things require the same skills, require the same brain, require the same amount of administration in some cases. But they need to do different things, so you’re talking about their effect. There are times when I need to put a floor on the wall to demonstrate that fifty-two schools were closed in Chicago, and then there are times when I need to fix the floor of a floor because its restoration has as much of an affect as putting the floor on the wall. Both of those things are art, but the signatures are not all registering as art, and I have to accept that.

Production still from Theaster Gates’s segment in Season 8 of Art in the Twenty-First Century. Art21, Inc. 2016.

There are times when I build buildings and they function like buildings. Then there are times when I’m reflecting on space and what comes out is more notably a work of art. Because there is this transgression between those worlds, there are times when people don’t know what they’re judging. Am I looking at a work of art, or am I looking at a building? But the question that I like better is “how do you spend your day?” and I spend my day making things. Sometimes I’m making things in my studio and sometimes I’m making things at a site that is somewhere else. But I’m always making or thinking about making, or encouraging and administering other people’s making. It’s a good question because in answering “how do I spend my day,” you also learn what I value. And what I value is not just studio time—I really believe that artists have other kinds of roles that we could play in the world, things that we would be good at, things that we could also leverage our skill sets for.

Sometimes I want to be about the business of good governance in our city, or the business of creating opportunities for other artists, or the business of these acts of restoration in a neighborhood where thirty percent of the buildings are vacant. All of that stuff, it goes in the same journal, it comes out of the same mind. They have similar weight. Not all of them go to museums, not all of them are made. Some of them are realized so that people who would normally go to museums in other parts of the world might want to come here and see this part of my practice too.