Teaching with Contemporary Art

Teaching Freedom: How Learning To Stumble Might Get Us Somewhere Worth Going

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

A real pedagogy of love, as proposed elsewhere, must go beyond simply caring about your students. Paolo Freire writes, “Love must generate other acts of freedom, otherwise it is not love.” If we love our students, which is a great place to start, it is essential that we talk to them about freedom.

Freedom has always been a loaded word. Freedom from what, and for whom? Free to what extent, and by what means? Not many self-proclaim as “anti-freedom,” yet as a society, we rarely agree on what freedoms are worth protecting and which seem to be more closely linked to oppression than liberation. Perhaps none of us have any clear idea what freedom really is because we’ve never truly experienced it. Lately, I’ve been wondering if my classroom is a space where students feel free. I’m sure they know I want them to be themselves, that they can make art about whatever they want, but do they know what freedom really means, in a more essential context? Do they know how to access it and engage it through their art? Do I even know? I started to wonder what could happen if I set my high schoolers free.

My school adopted a new mission statement this year, a thoughtful acronym of guiding principles fit to the letters P-R-I-D-E. I was surprised and heartened to learn that E would stand for empower. Ideas of empowerment cut through my teaching career, linking the teaching philosophy I drafted in graduate school right through to my most recent lesson. Oh, how I try to empower my students: to be who they want to be, and to think, make, and do what they want to think, make, and do. But what does it really look like to be an empowered 10th grader? What sorts of liberties should a high school senior be taking? While some high schoolers might conceptualize freedom in the form of skateboarding down the hallway and smoking cigarettes in the bathroom, I’m finding that freedom often presents as a more vast and terrifying idea to students. My kids are often eager to follow my step-by-step instructions, examples, and demonstrations, but what would happen if us teachers provided more questions and fewer solutions? If we value freedom, we must teach how to handle it, what to do when given it, and why we should defend it with our lives.

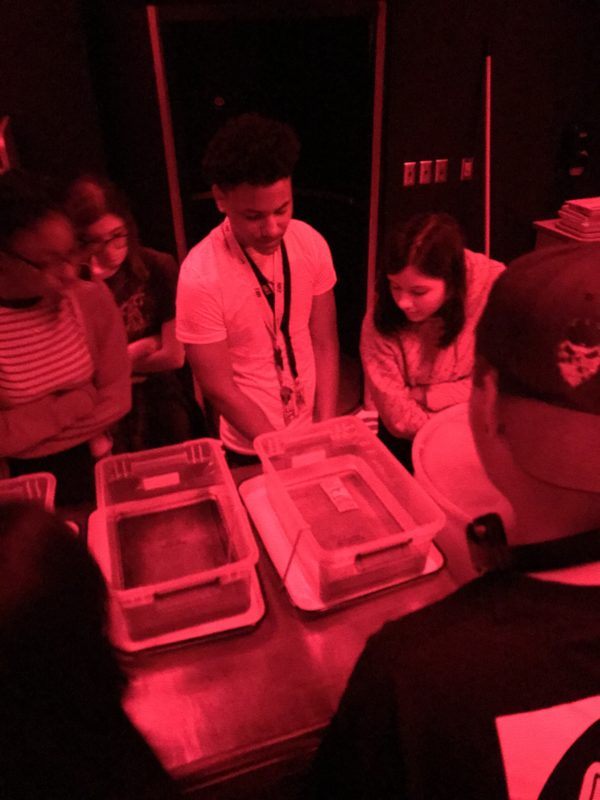

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

I’m working on a new theory about teaching freedom, and employing a metaphor of stumbling through the dark. I’m thinking about the feeling of moving through an unknown space, reaching out for forms and textures I can’t see. I’d say to myself, “If I could only see the contours of what’s in front of me, I could navigate this terrain and just maybe come out on the other side unscathed.” Maybe it’s the tumultuous two years of teaching during a pandemic, or maybe it’s just the greater circumstances of being alive and learning to make peace with the unknown. As a photographer and photography teacher, I’m acutely aware of the importance of shining a light on something with regards to exposure. But I want to suggest a different way forward when faced with the vast abyss of genuine freedom. Instead of turning the lights on for our students, what if we help them get comfortable with the feeling of stumbling through the dark?

The art room is a beautiful place to explore freedom and practice stumbling. I’m increasingly thrilled by projects with vague parameters and long stretches of unstructured work time. The discomfort my students feel at the start of these lessons is offset by the sheer variety of experiences and depth of thought that they eventually begin to pour into their artworks. Their awkward stumbling to find a solution to an artistic prompt seems requisite to getting somewhere that’s genuinely worth going.

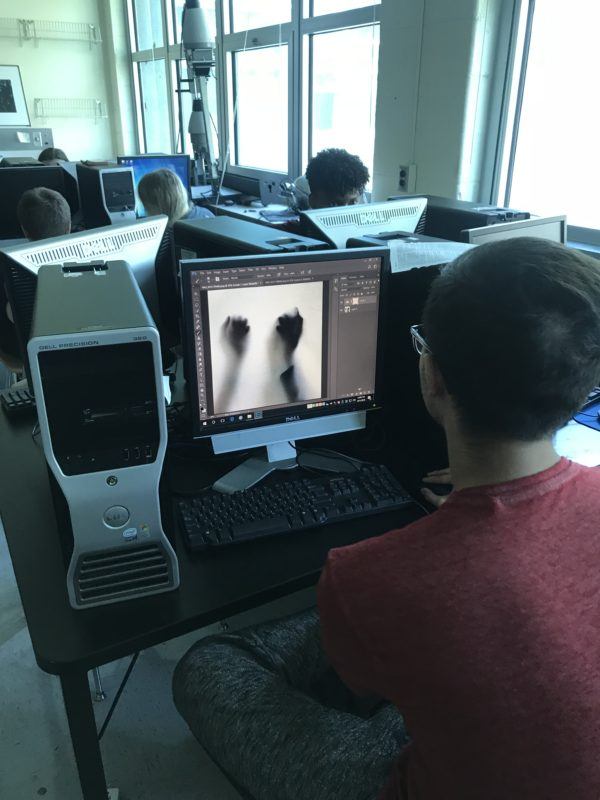

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

A few years ago I switched the way I approached teaching pinhole cameras to my students. In previous years, I had a 45 minute step-by-step video demonstration involving xacto blades, electrical tape, and pre-cut cardboard. The whole process took two 90-minute class periods, and students left with identical easy-to-use pinhole cameras with a focal distance that perfectly fit a pre-cut 4 inch by 5 inch sheet of photosensitive paper. The resulting pinhole photos were quite great! But while a few bright students gleaned the basics of optics, many seemed to learn very little about photography from that process. Plus, it was boring to teach (and I had to cut and trash so much cardboard)!

After a few semesters of it and some consultation with other photo teachers, I re-imagined the unit. After a single lesson about camera obscuras and lens optics, I put a random functional pinhole camera on each table of 5 students and told them to figure it out on their own. They had to make a plan for a new camera that would work, tell me what supplies they needed, and provide their own box. The next class they got to work, and we ended up with pinhole cameras made from everything from Apple & Eve juice boxes to Doc Marten shoe boxes, some covered in marker and tape, others in paint and glitter. (Side note for photo teachers reading this: iPhone boxes make great pinhole cameras!) When some cameras didn’t work as intended, students worked as a group to repair them. Eventually, they stumbled their way into a totally handmade pinhole camera. They were free to build and experiment and repair and shoot, and the results were wonderful.

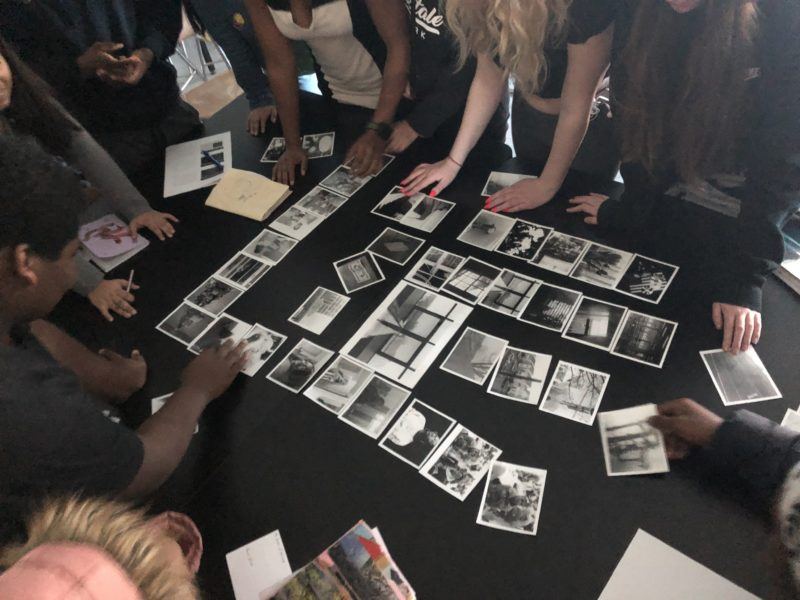

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

Sometimes I call this stumbling, but there are other times in my classroom where the feeling more closely resembles the sensation of freefalling. Stumbling in the dark might imply to some that there is a set space you’re bumbling about in; the room has walls, the problem has parameters. If you’re not comfortable with stumbling, you’re going to hate freefall. Not only are there no outcomes to work toward, you might find yourself with no idea what to do, nor where, when, or how. It is the ultimate kind of freedom in teaching art, and an exciting challenge.

Oliver Herring seated during a TASK event. Production still from the Art21 Extended Play film, “TASK,” 2014. © Art21, Inc. 2014.

The work of Oliver Herring comes to mind as I shape this distinction. First, there’s TASK. Herring’s TASK events or TASK parties are happenings in a predetermined space with a variety of materials (things like paper, ink, string, cardboard). They ask participants to follow two simple directions. According to Herrings’s website, the instructions are to “[W]rite down a task on a piece of paper and add it to a designated ‘TASK pool,’ then to pull a task from that pool and interpret it any which way he or she wants, using whatever or whoever is around. When a task is completed, a participant writes a new task, pulls a new task, and so on.” TASK parties are super fun and offer a unique way to break the ice with a new group. More significantly, they also provide an opportunity for students to experience working through seemingly random prompts with no real purpose beyond participation itself; as long as they participate in their freedom, they are free to do their tasks as they like. In the segment on Herring in Art in the Twenty-First Century, he says, “I don’t care too much about the medium, I don’t even care so much about the object. I really care about the process.” He’s not the only artist to suggest valuing process over product, and I’m not the first art educator to suggest the same philosophy in your art rooms. But TASK is a particularly excellent fit for exploring the idea of freedom as a self-directed artistic project in itself. It’s a perfect tool for educators who want to practice freedom, process, and stumbling with their students while providing the scaffolding of a designated space, materials, and a few guidelines.

Once your students have found their footing in the chaotic mess of a TASK, try removing the guardrails: What if there are no defined tasks to complete? What might they wind up making when left without instructions? What will they find themselves thinking about regarding topics like creativity and imagination, or their interactions with materials or classmates, or even their discomfort? What might your students discover about freedom when given a space and an opportunity, and otherwise left up to their own devices?

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

There are times in our personal lives when we might feel this sense of freefall. Sometimes this can be a really dark place — when you feel like a bright future is so unlikely or the way is so obscured that you’re not sure it’s worth the hassle. High schoolers might often feel this way, especially during a pandemic. This kind of unsettled feeling is a part of life. So I want to teach people, myself included, to better manage our discomfort in these periods that may feel like approaching certain ruin, but could alternatively be experienced as moments of freedom. I’m not suggesting freefall is a safe place to be. However, if we can learn to navigate it or to find the journey less painful, I suspect more of us will make it to the ground safely. Whether you’re at a crossroads or standing on the edge of a proverbial cliff, the process of figuring out what to do next and why could instead be considered an experience of freedom. And it’s just as traumatic for us to decide what to do and wonder if it’s the right choice as it is for our students. So let’s practice!

Abigail DeVille, 2018. Production still from the Art21 New York Close Up film, “Abigail DeVille Listens to History.” © Art21, Inc. 2018.

Contemporary artists make excellent role models to look to when trying to figure out how to create something from the unknown. I’m reminded of artists like Abigail DeVille, Edra Soto, and Nick Cave making art through discovery of discarded objects in their communities or at thrift stores. So many artists wind up developing incredibly poignant messages by just following through on a process without knowing where it was going. They stumble through dumpsters, littered parks, and secondhand stores until they discover the contours of an idea and find their way to a finished artwork.

These artists’ processes of experimenting and tinkering and reconsidering and getting lost and then finding their way should be held up as an example. To stumble your way into Great Art — how fantastic! It’s so hard to find one’s path; if we could train more people to do it and celebrate their achievements when they make it each step of the way, imagine the futures we could create for ourselves instead of settling for the comforts of the known. Furthermore, what implications might working through these periods of discomfort with the unknown have outside of the classroom? How could it bleed into other areas of thought and action and inform our openness to new ideas and big changes, like rethinking policing or immigration, or reimagining our approach to climate change or war, or any other problem we have as a society for which we lack a road map? Freefall is the condition in which progress begins. We can all agree that we want the world to improve, to get better, to progress. If only we could be more comfortable with the disruptive process of making things better.

Photo by Ariana Mygatt.

Some of us are afforded the privilege of getting to make more choices for ourselves in this life; questions from where to live to how to make ends meet are inextricable from our means and circumstances. But we are all capable of a certain degree of autonomy and agency. Learning how to stumble through life will help us all, teachers and students alike, cope with and manage the moments of freefall we encounter. For many reading this, two years of living through a global pandemic comes close to the sensation of stumbling around a dark, unfamiliar room, one that might not even have an exit. Let’s take stock of what we’ve learned about what to do when the lights are flipped off and we have to figure out what to do next. And then let’s take those learnings and focus on getting somewhere worth going.