Interview

Gestures

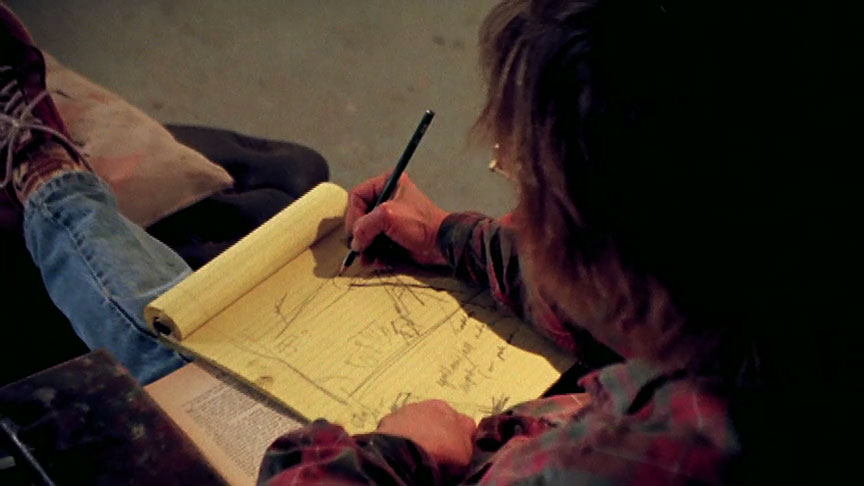

Susan Rothenberg in her studio, New Mexico, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Memory. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

Susan Rothenberg discusses her artistic motivations and her process of working in solitude.

ART21: What makes you come to your studio?

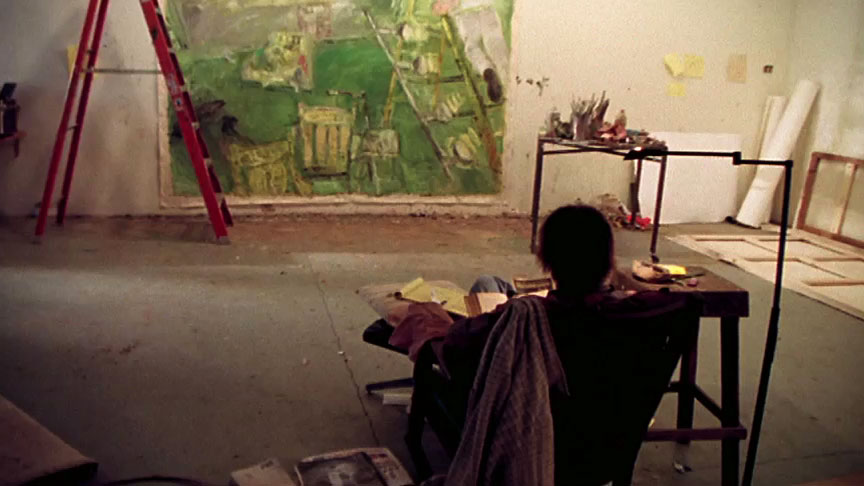

ROTHENBERG: No place else to go. (LAUGHS) No, I feel very strongly about putting time in, whether you’re working or not; reading a book is fine. But if you’re not here, it might pass you by. And sometimes you just throw your book down to the floor, march up to the painting, and say, “Something’s wrong here!” I pull the table over, throw my painting shirt on, and get going. Sometimes hours pass.

I almost always do something before I go in the house to watch the news—even a wrong stroke, a change in contour—just to have done some work that day. There’s the occasional day when I just don’t bother: I go to town, I meet people, go food shopping, whatever. But basically I am here from about eleven until five o’clock.

ART21: Do you find peace in the studio?

ROTHENBERG: Yeah, especially when there are houseguests or something. I say, “I have to go to work right now,” and the sense is, “Don’t come in.” It’s very peaceful with four dogs snoozing around me; it’s great. And I read a lot of fiction, biography, magazines, whatever is around.

ART21: Can you talk about drawing versus painting?

ROTHENBERG: The gesture of drawing—it’s very different from painting. And I’ve tried to bridge the difference by working with paint on paper as well as charcoal and pencil and graphite. One drawing I did on my stomach, kneeling and crouching over this big piece of paper, so that I couldn’t have any perspective, and so that I didn’t have that back-and-forth space between me, my arm, and the wall. And it turned out quite distorted, but it’s interesting. But the other way I’d like to think about drawing is cradling a board in my hand and drawing, without trying to emulate these big gestures that painting takes.

I haven’t drawn at all lately. I’m always engaged and embattled with the paintings and so anxious to move on that I have to bring these paintings around me to some kind of finality. I’d like to roll them or stretch them and put them on the rack, so I can find out what I’m supposed to do next.

Most artists really wish they had a series where one painting would lead to the next painting, and it would be a variation on it. That’s what happened in my early career—the horses. Now the paintings are more of a battle to satisfy myself with, and I do not have a sense of series. As you see here, there are two snake paintings, two paintings about this idea called meaningless gestures, two paintings that are a reflection of my domestic situation in the house. With each of them, the second painting seems to complete the series. I’d like to get a hold of something and be on that idea for a couple of years at least, but that’s not happening at the moment.

Susan Rothenberg in her studio, New Mexico, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Memory. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: Maybe two paintings is a series?

ROTHENBERG: Two paintings? I don’t know. Luckily I don’t have a deadline, so I don’t have to think about how these works would hang together and whether it would be too disjunctive. It’s an ongoing thing. And at least I’m not blocked. At least I find some reason to work just about every day.

ART21: Have you had periods of being blocked?

ROTHENBERG: Several months, sometimes. I make myself do something, but it’s terrible to have a couple of months where you’re disheartened because you think everything stinks in your studio. It happens—you go through all kinds of stuff—most of it’s pretty solitary. That’s what books are for. (LAUGHS)

ART21: Did you always imagine doing such solitary work?

ROTHENBERG: No, I was a very social kid up through college, past college. I don’t think anybody that knew me in high school or college would ever have thought that I would be successful at anything, much less spending 80 percent of my life alone in a white room, making work. It’s odd.

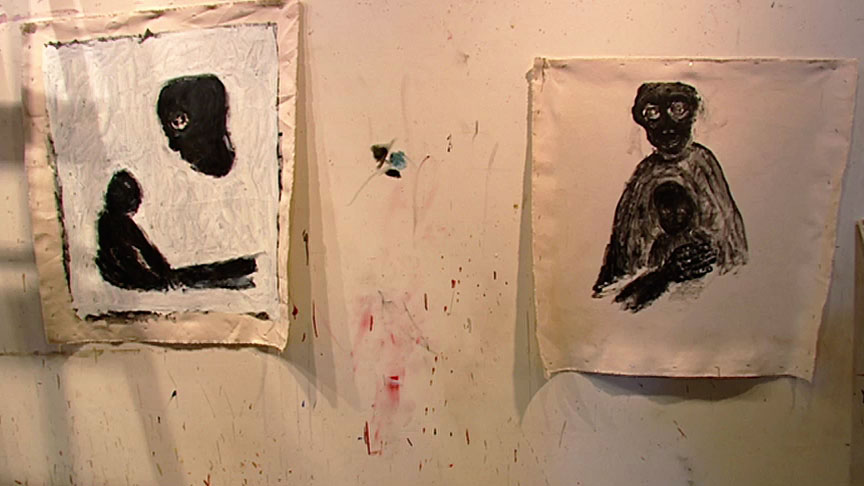

Susan Rothenberg in her studio, New Mexico, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Memory. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: Why did that happen?

ROTHENBERG: I think I went through a depression when I was around twenty-five. I did a couple of solitary trips to Europe, lived in Greece for a while, and tried to live in Israel. I came home, went to my parents’ house, and packed a suitcase. I tied the suitcase to a skateboard and took a train to Nova Scotia. I was going to go find a school to teach in. I thought I was going to teach English. (LAUGHS) English teacher!

And when the train was at an overnight stop in Halifax, I walked around McGill University. I had time to kill. And I met this woman; she was a folk singer. She invited me to her house for dinner, and then I was to go back to the station at midnight. I don’t know what happened, but I went up to the ticket counter, and I cashed in my Halifax ticket, and I bought a ticket for Manhattan. I got on a train full of Hasidic Jews. I put my suitcase in a locker at Grand Central. I started walking. At 14th Street, somebody I had gone to college with yelled my name. I said, “I just got into town. I don’t know anybody. I don’t know what I’m doing here.” He said, “Here’s my keys. I live on the top of the building on 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue.” And he was able to tell me where everybody from Cornell was in the city at that time, including Gordon Matta-Clark and Alan Saret—both practicing artists.

I had a loft within three months. It was a miracle turnaround. I thought I was supposed to be there, thought I was probably supposed to start painting again. And I met people whose names you would know, in every discipline—Phil Glass, Richard Serra, Keith Sonnier, dancers, musicians. It was absolutely, like, “No, you’re not going to Halifax; you’re going to New York. You’re going to meet people who are going to take care of you. You’re going to find your way.” It was a strange moment in my life. I was social the first year or two, then I had a baby, and that was the beginning of actively wanting solitude. Weird story, huh?

Susan Rothenberg in her studio, New Mexico, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Memory. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: It’s interesting.

ROTHENBERG: Yeah, that moment where I cashed my train ticket in is just so bizarre to me. It was as though somebody took me and turned me in a different direction.

ART21: You seized the moment.

ROTHENBERG: Yeah, I don’t even know what was in my mind right then, but I made it to the ticket counter and changed the ticket.

ART21: You used to paint before you got to New York?

ROTHENBERG: Yes, I had painted in college and while I was living in Greece, but I wasn’t very serious about it. In the first year, I also danced in Joan Jonas’s pieces, and I apprenticed with Nancy Graves. I went to every concert and dance performance I could. I just embraced the city. But after my kid was born, I couldn’t go out and party so much. It was the beginning of the solitary time, and it suits me fine.

ART21: Is any of that present in your work?

ROTHENBERG: That’s a hard one. I’ve done paintings about more psychological kind of stuff. I know that there’s something theatrical going on in, and I’m not sure I understand it. I started thinking about how many artists are making movies, and I thought, “I’m going to make my own movies and make them in paintings. I’m going to make them like love affairs and fights and anger.” Then I started to think, “What about making meaningless gestures that mean nothing?” And I thought that was amusing. So, I’ve done these two paintings, and now I’m stuck about that idea.

Susan Rothenberg in her studio, New Mexico, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Memory. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: How can a gesture be meaningless?

ROTHENBERG: Well, what is a meaningful gesture? When the gesture fits the action, I suppose. When it doesn’t fit any action, then it’s kind of meaningless. Like that painting over there—that’s a meaningless gesture. There’s a pair of clothes and an arm making a motion towards them . . .

ART21: This gesture could mean many things.

ROTHENBERG: Yes, but I don’t attribute any meaning to it. I just found a gesture and painted it three times. People read all kinds of things into my paintings that make me say, “Huh? What you think you’re seeing is not what I intended to be there.”