Teaching with Contemporary Art

Scenius, Inspiration, and Invention

“‘Scenius’ stands for the intelligence and the intuition of a whole cultural scene. It is the communal form of the concept of the genius.” —Brian Eno1

Despite the fact that his name appears on the covers of the albums Another Green World and Ambient 1/Music For Airports as their primary author, Brian Eno has made clear his understanding that musical compositions and other creative inventions emerge primarily from social contexts, or scenes, rather than from the solitary mind of a lone genius.

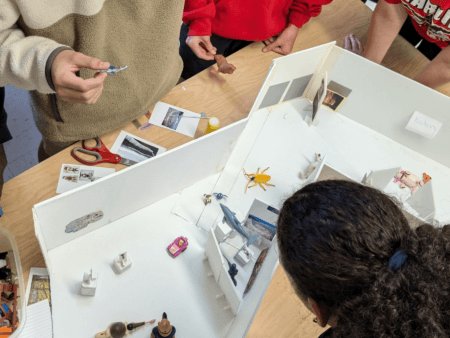

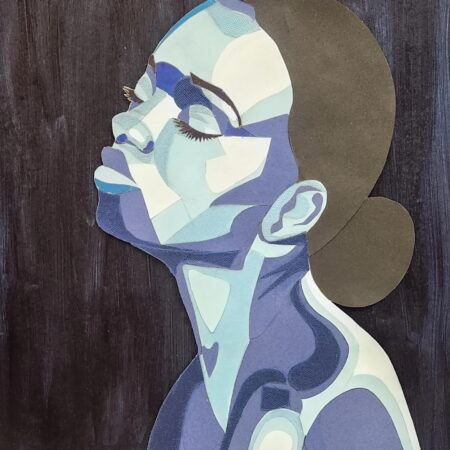

I see my art classroom—the teaching, learning, and artistic practices that go on there—as a small-scale manifestation of Eno’s concept of “scenius.” When creativity and invention do show up in the classroom, they are, more often than not, socially constructed. I’m sure others who teach art have also observed this: students working near each other, observing one another, taking note of, copying, and riffing off each other’s formal strategies, visual motifs, and thematic ideas. Experimental techniques arise and spread through classes and across multiple periods throughout the day. Variations on those techniques develop over time. Recently, a technique caught on like wildfire in my art classroom: the transfer of the shiny coating from metallic-plastic sheets onto collages and drawings. This novel practice varied in appearance in different students’ artworks, but it emerged in all five of my classes. I like to call attention to and discuss these socially spreading innovations when they happen and to connect them to practices by contemporary artists. I recently shared a quote with my students from Michael Dumontier of the Canadian collaborative artists’ group, Royal Art Lodge. Dumontier spoke about the collective and social dimensions of his group’s artmaking in this way: “It’s sort of anonymous. Your contribution kind of dissolves into the bigger picture, which is a kind of freedom that’s helpful in clearing your mind to experiment.”2 I think this is a good description of the scenius-like qualities of art classes, and many of my students appreciated knowing that successful contemporary artists also participate in socially constructed creativity.

The scenius dynamic also informs my curriculum-design process as well as my daily “teacher moves.” When developing a new curriculum, I think of myself as a member of local and global scenes. My peers are contemporary artists, educators, writers, poets, musicians, designers, researchers in non-art disciplines, and often my students. I’m open to being influenced by these peers, and to the extent that I innovate or even invent new curriculum forms, they rarely emerge from a vacuum.

Ideas for curriculum provocations, interventions, and strategies come to me in a variety of ways. Like many of my art-teaching peers, I build from what I see happening in the classroom and, for my students, I draw connections to contemporary art and artists exploring similar terrain. And, inspired by the strategies of contemporary artists and other kinds of investigators, I construct artistic explorations for the students that build upon these approaches.

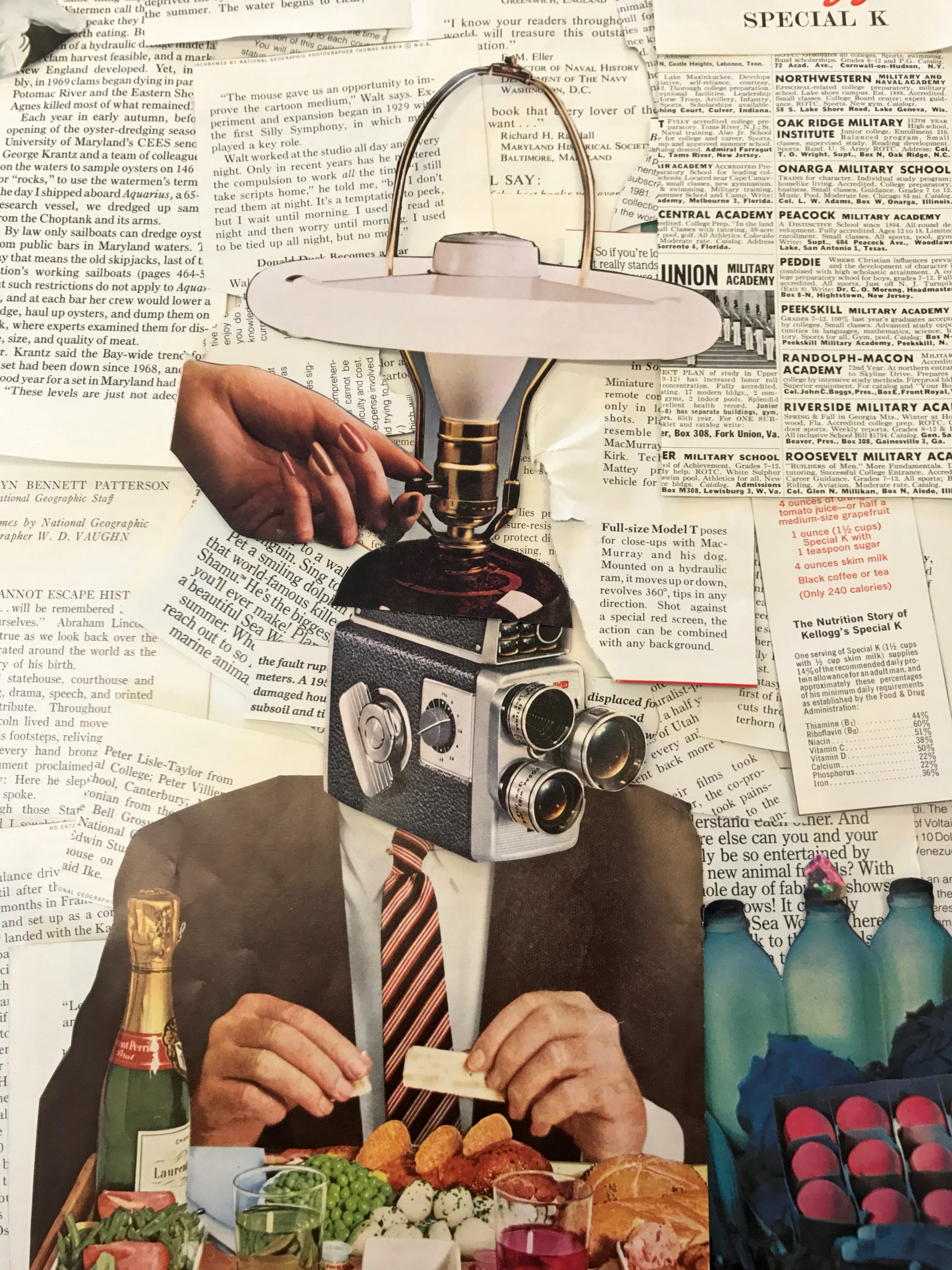

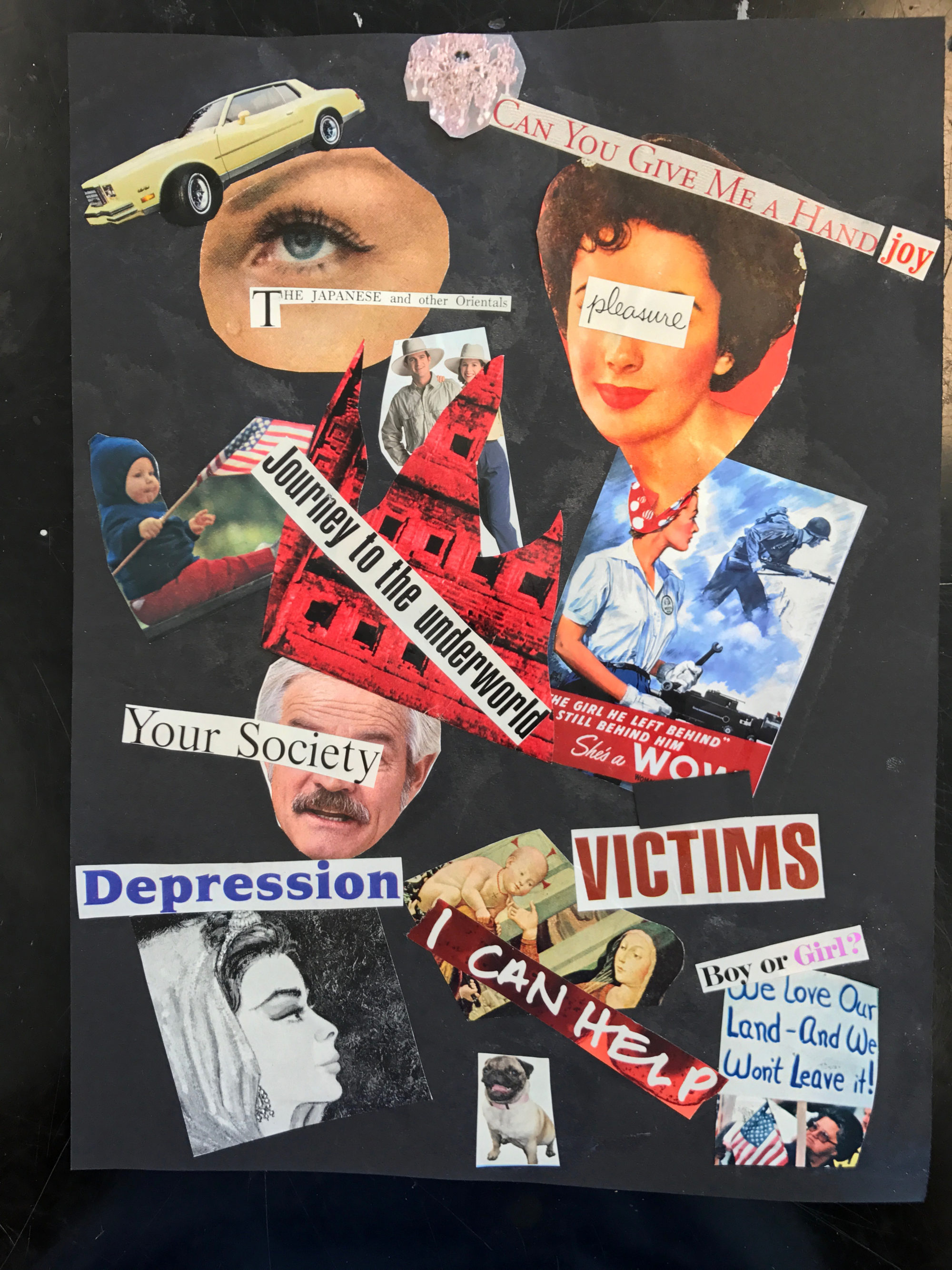

An example of this occurred recently when I noticed that many of my students were incorporating advertisements from vintage National Geographic magazines into their collage assignment. A striking number of them were juxtaposing the advertisements with other images and texts. Some compositions were made in order to make explicit political points; others mashed up the images from ads in a more playful manner. Seeing my students’ appropriation of advertisements in their collages, and noting that they were using them in both political and playful ways led me to share with them the work of LaToya Ruby Frazier and Ellen Gallagher. Both artists have deployed appropriated advertisements in their work; my students had been using ads in surprisingly parallel ways.

In Frazier’s politically charged alterations of a series of advertisements from the Levi’s “Go Forth” advertising campaign (shown at the 2012 Whitney Biennial), the artist critiqued the print ads and, by extension, the corporate practices of Levi Strauss and Company and the destructive forces of postindustrial capital in the Rust Belt. By writing directly onto and in the margins of the Levi’s ads, Frazier revealed and responded to the embedded meanings in the ads and brought forth the ways in which her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, was used in various problematic narratives conveyed through the ad campaign. In these works, Frazier presented her critical dialogue with Levi’s in a clear and explicit way. For my students who were creating politically themed collages, Frazier’s annotated Levi’s ads were powerful and validating examples of how contemporary artists can successfully engage in a public dialogue about the important issues of our time.

In a sense, Ellen Gallagher’s use of appropriated advertisements from the magazines Ebony, Jet, and Sepia—in her print series Deluxe and in a series of large-scale works on canvas entitled eXelento—is no less political than Frazier’s work. These works, featuring ads drawn from magazines aimed at African-American consumers from the 1930s to the 1970s, focus on various aspects of Black culture in the twentieth century, particularly on notions of beauty. In addition, these magazines functioned, as Gallagher points out, as a Black press and as such presented a counter-narrative to overtly racist representations in the larger American culture. Despite the ways that the artworks in eXelento and Deluxe function politically, Gallagher does not see them as vehicles for direct political messages: “I think people get overwhelmed by the super-signs of race when, in fact, my relationship to some of the more over-determined signs in the work is very tangential.”3 Gallagher’s playful altering of the hairstyles and eyes of the models in the magazine ads, using yellow Plasticine and other layered collage elements, is intended to prod viewers into “an imaginative space” of “mutability and moodiness” rather than toward explicitly political readings of the work.4 Gallagher’s work strongly resonated with my students who were collaging advertisements in more intuitive and even humorous ways. Some of them reported that Gallagher’s work made them realize the possible political undercurrents in their collages of advertisements and other imagery, and still others were inspired by the inventiveness and whimsy in the ways that Gallagher altered the appropriated ads in her work.

The influence of my students’ use of advertisements in their collages and the connections we found with the work of Gallagher and Frazier has inspired the development of a new curricular project. This exploration will involve my students taking a deep dive into the mountain of donated National Geographic magazines in my classroom, to excavate the advertisements. I’m envisioning students cutting out the ads and grouping them together to see what is there and begin to analyze the ads’ content. I want to encourage the students to think of themselves as anthropologists or ethnographers and to widen the investigation to also look at the editorial content of the magazines. I also want to incorporate language into this exploration; I have invited a couple of my poet friends to collaborate with me and the students on this project, which brings to mind the work of Glenn Ligon, whose text-based work could be another inspiration for this creative inquiry. Of course, the directions that the students take with their investigations and what they create will be up to them. There are certainly no shortage of exemplary contemporary artists, writers, and researchers who use a wide range of forms and strategies to explore the complex terrains of visual culture. These practitioners are our scenius peers, who inform, inspire, and prod us on to new discoveries.

1. Bruce Sterling, “Scenius, or Communal Genius,” Wired, June 16, 2008.

2. Kevin Nelson, “Magic Children: The Fantastical World Of The Royal Art Lodge,” Whitehot Magazine, February 2008.

3. Ellen Gallagher, “eXelento and DeLuxe,” Art21.

4. Gallagher.