Interview

Studio as Laboratory

Addressing questions of how objects acquire value, Sarah Sze posits that being an artist is about giving yourself permission to make choices.

Art21 What was the influence of science and architecture on your work?

Sze My father is an architect, so I grew up around models and plans, looking at construction sites with his eye, always talking about buildings and cities. That’s definitely part of how I learned how to see the world.

Charlie Ray [once] asked me in an interview, “Do you know what was the first work of art you ever made?” It was maybe this: My dad had built a house, and there was a big mound of dirt that was left from digging the foundation, and my brother and I dug a hole through the bottom of it. We’d go inside the hole, and it was quite dangerous because it [seemed to be] floating; we couldn’t see out. This experience of hiding, knowing that it could collapse on you—I feel like that, in some ways, was my first sculpture.

What early experience of artwork moved you?

I think that most artists are addicted to looking as much as they are to making art. From a very young age, I was making art. I was always thought of as the artist in the house, in whatever class I was in. The moment I realized that I was really going to become an artist was when I tried to stop making art and had the profound sense of loss and disorientation and the knowledge that looking at art had been such a sustenance and always will be. Those two things are married very closely: looking at art and making art. That’s when I really started doing it, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to not do it.

I grew up going to museums all the time. I grew up looking at buildings. I think my work became interesting when it related less to knowing about art than to thinking about experiences I had in the world that were completely unrelated to art.

I had a strong undergraduate education in art history, but that doesn’t make you a good artist. Even when I went to graduate school, I think my work was very accomplished in certain ways but fundamentally not interesting. It wasn’t until I figured out how to find a location—where information in my life and the rest of the world surprised me—that the work became interesting enough for an audience.

I was a painter and an architect, in the beginning. I started thinking about how gravity is something that you don’t have in painting. As a sculptor, I’m trying to make things that sit in between… I’ve been thinking a lot about traditional perspective in Asia and in the West: how those two meet, and where they don’t meet, and how you can play with the two of them.

How did your experience of studying in Japan affect you?

Living in Japan was a profound experience because it showed me how aesthetics and art, and the way they can be integrated into your life, could be entirely different in another culture. The way that artworks are integrated into the everyday in Japan is so different from here. To see that shift—in the way people looked at beauty, aesthetics, the handmade, the machine-made, and valued those things—made me reconsider how our culture does it.

Sarah Sze incorporates an orange onto her High Line sculpture Still Life with Landscape (Model for a Habitat), 2011. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 6 episode, “Balance.” © Art21, Inc. 2012.

Can you talk about the use of ordinary, found materials in your work?

I was interested in value: How does an object acquire value? Why is it more valuable in the museum than in your house? How do things we own acquire value? How does a shirt that you know thousands of other people own become yours? How do you sense that an object is cared for or valued? [I wanted to] take things that had very little value—that were commonplace, mass-produced, easily accessible, easily replaced—and put them in a location, to craft and juxtapose them in a way that they seem to have value, so that there was a strong shift, and then back again to being nothing. That was something I wanted to play with.

Was this a spontaneous thing?

It’s a balance; the spontaneity is always where it’s the most interesting for the artist and for the viewer. You can spend a lot of time conceptualizing and thinking it over, and then it’s usually in the process of making where there is something spontaneous that, after all that planning, you had no idea was going to happen. When that happens is when it’s interesting.

Improvisation is crucial. That goes to this very old idea: How do you breathe life into a sculpture? When you look at a Bernini, you see how marble becomes an arm—how does an object that’s inanimate come alive? I think that improvisation is crucial to the whole process, in that I want the work to be an experience of something live: a feeling that it was improvised, that you can see decisions happening on site, the way you see a live sports event or see live jazz and [know] that it happened and is never going to happen again. That feeling—of something happening in the moment—is crucial.

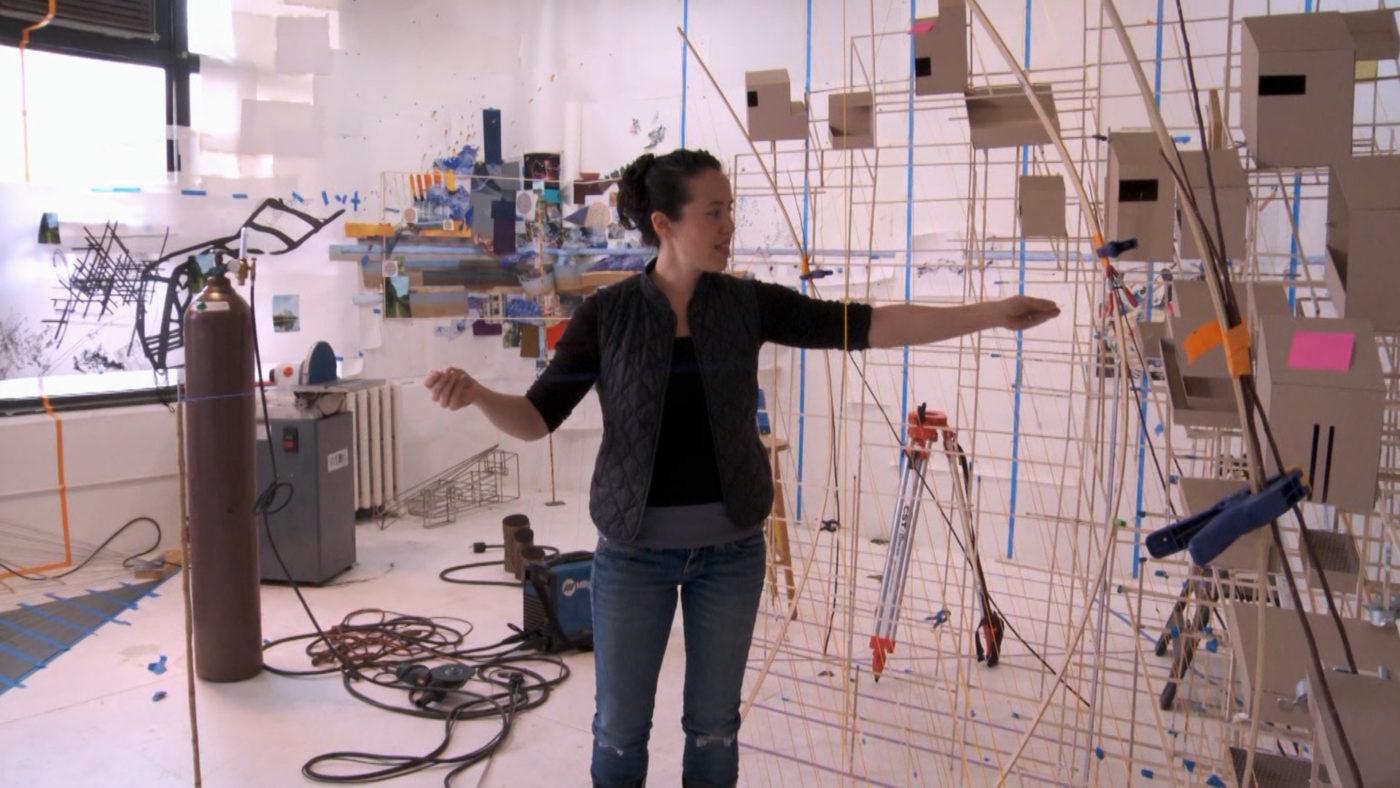

A lot of the works have this feeling, like going into a studio space or a laboratory. [This feeling] also has a relationship to intimacy: how a studio visit can be more interesting than a museum show or an Art21 interview can be more interesting than an [exhibition] catalogue. [It suggests] the idea that you’re getting a backstory of evidence: you’re going to an archaeological or forensic site, seeing what’s behind a process and even a culture, and starting to understand behavior.

I think about how we read behavior through objects and space and how to develop an interest in the viewer. What behavior is happening here? How does a work become evidence of the behavior of an individual or of a culture?

Sarah Sze details her High Line sculpture Still Life with Landscape (Model for a Habitat), 2011. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 6 episode, “Balance.” © Art21, Inc. 2012.

Is there a sort of delight in making work for you?

In the process of making art, there’s a window of real joy that happens in the studio, usually about three-quarters of the way through the process, for me. By the time I get past that, I’m thinking about the next project. Part of the way that I finish a project is by being on another project. I think part of being an artist is actually giving yourself permission to make choices and not judge them. There are ways that artists trick themselves into creating a mindset that allows for that kind of openness. One of my ways is that I think about another piece as I’m making a piece, so I can cut off the judgment that I think we all have, questioning an action before it actually happens.

That’s the hardest thing about being an artist: being able to trust an action when it can be a completely absurd decision, to trust that the outcome might be quite fruitful. It might not be, and then you have to have the resilience to pick yourself up and try something else. You also have to have a way of cutting off the [internal] judging of what you’re doing, so that you can see results and respond to them. The work makes the work, so you have to keep making the work, even when it’s failing, and working through it so that you can make progress.

What do you think about permanence and longevity, in relation to your work?

I think it is interesting to question the future of the work. I have this relationship with the work, where I think: How long did it take to make it? How long will it take to take it down? Where does it go? This is true of any painting or sculpture: how is this possible? I did my graduate thesis on the life of artwork over time and looked at how different artists took this on. One of the most interesting people is Félix González-Torres because he knew he was going to pass away, so he documented each work precisely but in a very idiosyncratic way. It was liberating to me to adopt his philosophy, which is that each piece needs a specific set of directions for [the future of] that piece.

This interview was originally published in the Art21 publication, Being an Artist.

Interview: Susan Sollins. Editor: Tina Kukielski. Curatorial and Editorial Assistant: Danielle Brock. Copy Editor: Deanna Lee. Published: September 2018. © Art21, Inc.