Interview

Water

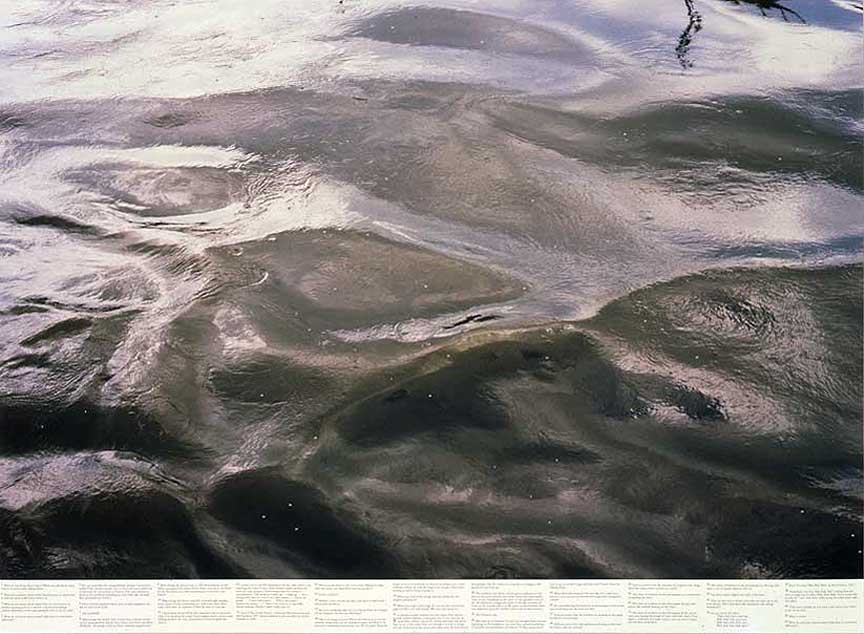

Roni Horn. Doubt by Water, 2003–2004. Installation view at Hauser & Wirth London, Piccadilly, United Kingdom, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Structures. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

Artist Roni Horn discusses her works Doubt by Water, Some Thames, and Still Water.

ART21: There’s a new element in Doubt by Water. What is it?

HORN: Doubt by Water is a form that I’ve been thinking about for a while. It starts with a two-faced image. That’s really the core of the whole work: getting a two-faced image (which is more or less like an object) into a meaningful relationship to space, and the form with the stanchions in relationship to the architecture and flow-through. It was an interesting kind of balance to hold together the many pieces going throughout an architectural setting—and the river, the glacial water, which is the gray surface, is a kind of cohesive link.

I think that image, or that way of shooting water, was very much influenced by Some Thames and some of my other works from London, where you just kind of get the surface of the water, its relationship to the weather and light. Then, the other side was various motifs that have occurred in different forms in other works. One is the young person—a kind of a portrait—and repetition with a slightly different nuance throughout a space. And you’ve got the ice, the birds, the faces of the birds, the portrait.

ART21: What about the birds?

HORN: They were stuffed birds.

ART21: Where did you find them?

HORN: This all started when I was shooting a piece called Pi, which was completed in 1997–98. I went and photographed the collections in Reykjavik, of stuffed animals, and specifically was working with the indigenous animals of Iceland. And those were intended to be part of Pi, but of course I wound up photographing extensively and other things came out of it. I’ve amassed this rather large archive of images from Iceland over the last fifteen or twenty years. A lot of it’s just taken with no intention on my part or with lost intentions—something like that. So, none of the material you see here was ever used before, but it was taken back in 1991. And the portrait is very recent: 2002.

ART21: So, you created a vast image bank?

HORN: Unintentionally, I have a collected a lot of material. By “unintentionally,” I mean the idea wasn’t to have a large image bank, but nevertheless I have one now. So, I fall back on that. When I was putting this work together, I knew that I wanted disparate motifs coming together—it was very particular what would work and what wouldn’t. I had actually gone to Iceland to photograph specifically for this piece, and none of that material was acceptable to me. So, I fell back on this archive, and I guess it’s also a kind of a memory thing, because it’s all, in a way, a history. But that’s not really part of the piece, I don’t think.

ART21: What do you mean by “not part of the piece”?

HORN: I don’t think it’s important to a viewer that these images were taken over a ten-year period. I don’t think it is interesting to the piece in any way; that’s just how I work. Often the objective is not clear for years after the act. It’s a very odd way to work; it’s a little bit backwards, but it’s how I do it.

IMAGE

ART21: Talk about how this work relates to drawing.

HORN: I always think of everything in terms of drawing, and there’s definitely a drawing element in putting together these visual relationships and composing these objects in a space. It’s the many layers of relation that make the work effective.

When you see Doubt By Water as a group, it’s sort of operating as an object. But as you use it to pull someone through space, it functions more like an image, an icon. So, the piece flickers between a three-dimensional experience and a kind of two-dimensional image. I really wouldn’t know how to describe what this work is. But it has a very particular way of moving the viewer through space and through image space, which is very different than architectural space.

ART21: Describe how you set this up.

HORN: Doubt by Water is intended to be installed throughout a building. Starting from the entrance—which is always a pivotal spot in terms of the development of an experience—I would move Doubt by Water throughout this space, using transition spaces, the halls, that kind of thing. And then, perhaps, a little pooling, grouping of doubt, occasionally. It’s moving between this signage to the object installation. It’s interesting in the sense that I notice when I’m installing: it’s very hard to install because it’s viewable from every angle. With most three-dimensional objects, the relationship to the space is somewhat fixed, and here it isn’t. As you walk around the grouping, these images are coming and going; you’re seeing some, and others are dropping out. All of that has to be composed. I guess I was surprised at how complex that was; I thought that would be a little bit easier.

ART21: Talk about that.

HORN: It acknowledges the body, and it acknowledges the eye. With photographs, you’re not dealing with the presence of the figure, the viewer as a body; you’re really dealing with the eye. But sculpture’s dealing with the physical presence as well.

Roni Horn. Doubt by Water, 2003–2004. Installation view at Hauser & Wirth London, Piccadilly, United Kingdom, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Structures. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: Say more about the water in Doubt by Water.

HORN: Aside from the physical, sensual reality of water, the thing that I love is its paradoxical nature. I never intended to have water in everything I do, but I almost feel like I rediscover it again and again. It just finds its way back into new work.

ART21: What are some examples of its paradoxical nature?

HORN: Water is a very dependent form. It’s completely dependent; its shape is determined by things not water, whether it’s a river or a glass. So, you have this essential material that is entirely dependent on its neighborhood and its neighbors. It’s also an extremely tolerant form, meaning that it’s a solvent for many things. So, everything finds its way into water. And water can still be water and accommodate a lot of different presences.

The big paradox is: “How does it still keep its transparency?” That’s what I’ve wondered about. The water you drink—who knows how many times it’s been around the world?—and its appearance is still wildly constant. Obviously, it’s dependent on light and weather and all of these things. But water in the glass looks like water halfway around the world. It’s pretty much identical.

So, there is this interesting aspect of the constancy of water and its multifarious expression, geologically and so on. You have an identity that has an endlessly changing appearance. Or you have an identity that has an endlessly constant appearance. It has both of these things. I think of water as a verb; I think of it as something one experiences in its relationship to other things. Obviously, I’m thinking about it in Iceland, for example: the presence of water is so extensive, and it’s always circumstantial.

Roni Horn. Doubt by Water, 2003–2004. Installation view at Whitney Biennial 2004, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo by Bill Jacobson. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

ART21: Can you talk about the project where you photographed the Thames?

HORN: The problem with that project is that there are a dozen projects, and I get them all confused. The big project started out as an artist’s book, Another Water, which was the idea of shooting the surface of the water as a continuous event and footnoting the entire extent of it. So, that’s how the book was laid out—bled pages of the surface of the water taken over a one-year period.

ART21: When was that?

HORN: That was when I was researching the [River] Thames. I decided only to cover the central London part of the river, partly because of this very rich relationship the city has to the river, the history, but also the daily intercourse with it. All of the photographs in Some Thames, Another Water, and Still Water were photographed in central London.

And there is your paradox: that every photograph is wildly different, even though you could be photographing the same thing from one minute to the next. It’s almost got the complexity of a portrait, something with a personality. Of course, the Thames is an especially beautiful river to photograph because the weather here is so indecisive; it’s rarely blue skies, which would be the least interesting light to photograph water in. The Thames has this incredible moodiness, and that’s what the camera picks up. It is also about it being a tidal river, so it has these vertical changes, and it moves very quickly. It’s actually a very dangerous river, and you sense that just by looking at it.

I thought I would shoot the Seine or the Garonne, but these rivers don’t have the same energy. I don’t know how many people kill themselves in the Seine, but it just didn’t look like a convincing suicide route to me. The Thames has the interesting fact attached to it—that it is the urban river with the highest appeal [for] foreign [suicides], so you get people coming in from Paris to kill themselves in the Thames. So, it has an incredible draw. And one of the points about shooting the Thames was the fact that it’s darkness was quite real: it wasn’t just a visual darkness, it was a psychological darkness.

Water is something one’s attracted to largely for the light aspect of it. And the banks along the Thames—a lot of them are being restored or renovated, and the view is on this very dark water. There was this paradox: even in its darkness, it has this picturesque element. It’s something about the human condition—not the water itself—humanity’s relationship to water. So, in the end, it doesn’t make a difference what the water looks like. It will always have this kind of picturesque quality to it because that’s almost a human need–that water be a positive force.

Roni Horn. Still Water (The River Thames, for Example)—Image C, 1999. Offset lithograph (photograph and text combined) on uncoated paper; 30 1/2 × 41 1/2 inches. Edition of 7. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

ART21: And the installation of Some Thames at The University of Iceland in Akuryeri?

HORN: The idea is, again, to flow it through not only the building but through the actual use of this space. Someone using the building might take weeks or months or years to ultimately discover the extent of the work because it is, throughout, a complex of buildings, and the logic of it is kind of leveling. The various spaces are used by different aspects of the university. One’s relationship to a building is in this repetitive cycle: you walk down the same hall, and you go to the same bathroom, and you exit and enter the same way. Occasionally, you stray out into other parts of the building. And then, as your relationship to the space evolves, more and more of the work is revealed.

I like the idea that the scale of the work is unknown but pervasive. This is a work that goes throughout the complex of buildings, not dominating it but setting a tone for the space. I am really not concerned that students see it as art. It is a permanent installation, meaning that person using the building will experience different parts of the piece over the years that they spend there. So, that was the intention with Some Thames, to have eighty large photographs deployed throughout a social setting like this. It’s almost too small, so I’m a little concerned about that. But that’s an ideal setting for the piece, as opposed to the Dia [Center for the Arts], where they were hung in a traditional way—a four-wall installation very tightly hung—and you had about half the installation there. That hanging had other qualities to it, but they weren’t as interesting to me as setting up this dynamic with the viewer.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2005 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.