Interview

Light and Music

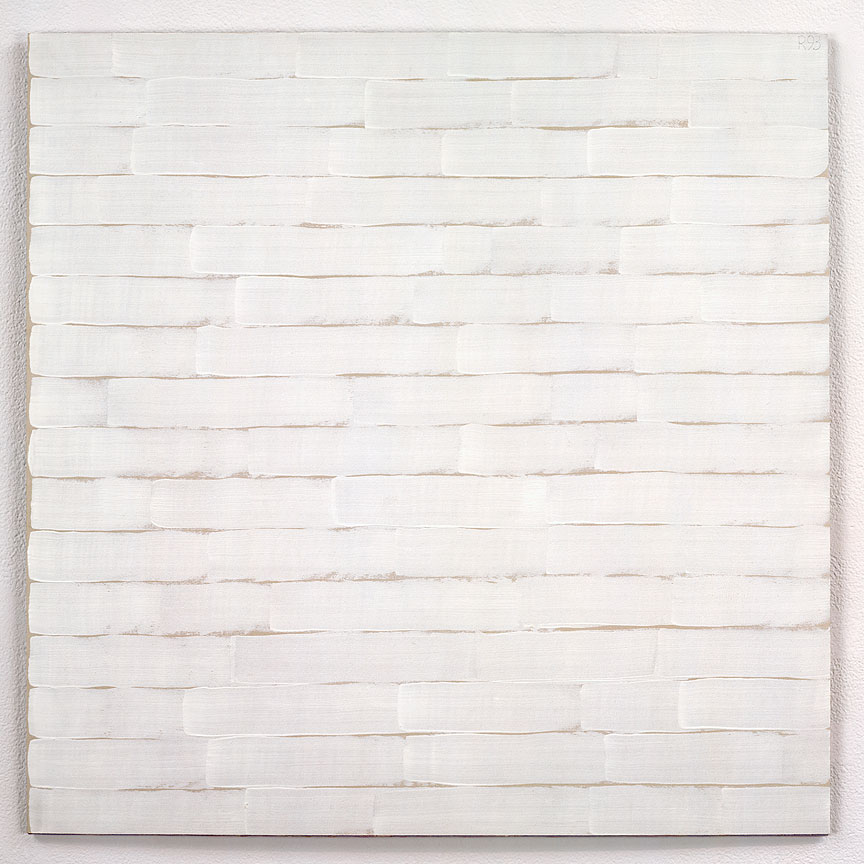

Robert Ryman. Hansa, 1993. Oil on canvas; 53 1/8 x 53 1/8 inches. Private Collection, New York. Photo by: Ellen Page Wilson. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York.

Robert Ryman talks about his approach to painting, and the influence of music in his work.

ART21: How do you approach making a painting?

RYMAN: My approach tends to be from experiments. I need the challenge. If I know how to do something well, there’s no need to do it all the time because it becomes a little monotonous. So, I like to find a challenge. Of course, all these things are rooted in the basics of painting. It’s not that I do anything crazy, but I tend to work within a structure and see what other possibilities there can be.

ART21: Light is very important to you.

RYMAN: I use real light, so there’s not an illusion of light. It’s a real experience. The lines are real. You see real shadow. If the paintings are seen in a daylight situation, it’s very important where that light comes from; it’s a matter of direction. In many museums, you see paintings under the same light all the time, under electric light. So, you go in the morning, and it looks just like it does in the afternoon. That’s the best that you can do, sometimes. But if you can get daylight that comes from above or opposite a painting, that’s the best, because it changes with the clouds and with the sun moving—so you always see the work differently. If the light comes obliquely from the left or the right, that’s not good because you get a raking light across the work. And it’s a distortion of the painting. If you can get the right lighting situation, it’s very important for all painting—but particularly my work.

ART21: Where does this attention to light come from?

RYMAN: From looking, seeing things, looking at everything—but painting, particularly. And of course painting is a visual experience, so it only happens when we see light. (LAUGHS)

ART21: Is the light something you think a lot about, when you work?

RYMAN: Yes. I think about it when I’m working because I look at my paintings under different lights—bright lights and then in daylight.

ART21: New York has amazing light.

RYMAN: When I first came to New York, I don’t know that I noticed so much about the general light in the city. Of course, the best light is right after it rains, when you have that soft reflective light. But when I first came to New York, I would just hang around in Times Square and look at the lights; that was something I had never seen before. It was the electric lights that were fascinating. (LAUGHS)

ART21: Did you come to New York knowing you wanted to be an artist?

RYMAN: When I came to New York from Nashville, it was music that was the most important thing. I was studying and practicing. But I went to museums, and for the first time, I saw paintings that interested me not so much because of what was painted but how they were done. I thought maybe it would be an interesting thing for me to look into—how the paint worked and what I could do with it. I looked at everything. I didn’t know anything about art. I didn’t even know any artists. I accepted everything; I had no prejudice. If it was in a museum, it was a good thing. When I got a job in a museum, it was ideal for me. That was a fantastic education.

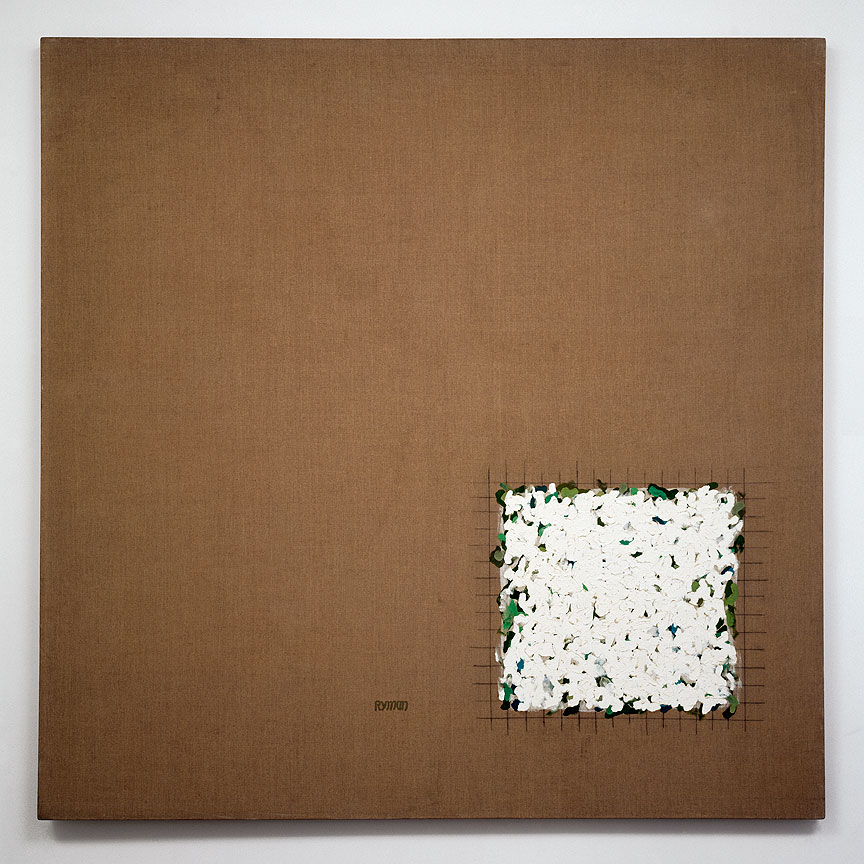

Robert Ryman. Untitled, 1962. Oil, gesso and charcoal on linen; 74 1/4 × 74 1/4 inches. Private Collection, New York. Photo by: Ellen Labenski. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York.

ART21: Is music an influence on your work?

RYMAN: I came from music. And I think that the type of music I was involved with—jazz, bebop—had an influence on my approach to painting. We played tunes. No one uses the term anymore. It’s all songs now, telling stories—very similar to representational painting, where you tell a story with paint and symbols. But bebop is swing, a more advanced development of swing. It’s like Bach. You have a chord structure, and you can develop that in many ways. You can play written compositions and improvise off of those. So, you learn your instrument, and then you play within a structure. It seemed logical to begin painting that way. I wasn’t interested in painting a narrative or telling a story with a painting. Right from the beginning, I felt that I could do that if I wanted to, but that it wouldn’t be of much interest to me. Music is an abstract medium, and I thought painting should also just be what it’s about and not about other things—not about stories or symbolism.

ART21: You don’t think of meaning?

RYMAN: There is a lot of meaning, but not what we usually think of as meaning. It’s similar to the meaning of listening to a symphony. You don’t know the meaning, and you can’t explain it to anyone else who didn’t hear it. The painting has to be seen. But there is no meaning outside of what it is.

ART21: So, meaning is closer to an emotional reaction?

RYMAN: I think that’s the real purpose of painting: to give pleasure. I mean, that’s really the main thing that it’s about. There can be the story; there can be a lot of history behind it. But you don’t have to know all of those things to receive pleasure from a painting. It’s like listening to music; you don’t have to know the score of a symphony in order to appreciate the symphony. You can just listen to the sounds.

ART21: Do you think of your work as abstract?

RYMAN: I don’t think of my painting as abstract because I don’t abstract from anything. It’s involved with real visual aspects of what you are looking at—whether wood, paint, or metal—how it’s put together, how it looks on the wall and works with the light. The wall is involved with the painting. Of course, realism can be confused with representation. And abstract painting—if not abstracting from representation—is involved mostly with symbolism. It is about something we know, or about some symbolic situation. I don’t make a big deal about this realism thing. It just seems that what I do is not abstract. I am involved with real space, the room itself, real light, and real surface.

ART21: There’s a real challenge to the concept of objectivity in your work.

RYMAN: Well, I’m certainly not the only painter working this way. The Guggenheim Museum used to be called the Museum of Non-Objective Painting.

ART21: How does your work fit into the contemporary art world?

RYMAN: I don’t think of myself as being part of anything. I don’t get involved with art. I mean, I’m involved with painting, but I just look at it as solving problems and working on the visual experience. I’m not involved with any kind of art movement, and I’m not a scholar. I’m not a historian, and I don’t want to get into that kind of thing because it would interfere with my approach. So, it’s better that I not think of that. (LAUGHS)