Interview

Art & Life

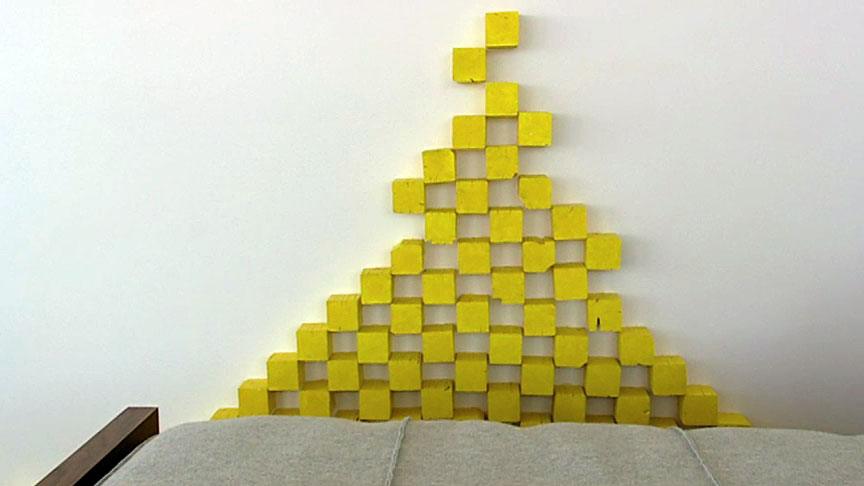

Richard Tuttle. The Klein residence, Tesuque, New Mexico, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Structures, 2005. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

Richard Tuttle talks about how he first became an artist, and the rules he applies to his art-making process.

ART21: Measurement seems to play a big part in your work.

TUTTLE: A kind of strange part of my work is that one instant is the same as all time, all eternity—microcosm, macrocosm. One of my favorite artists is Jan van Eyck, who gives you a picture that satisfies all attentiveness to the smallest of the small and all attentiveness to the largest of the large. That’s one of the things that a picture is supposed to do for us. Ultimately, you have to come to that flash instant, which is almost un-measurably short and then un-measurably large. I’ve always been confused why we have this system where we try to balance out original time with non-original time—you know, sequential time by the watch and then the concept of time. Even our sentences, the ways we express ourselves, play service to each one of those notions of time.

ART21: Talk about what happens when installing your work.

TUTTLE: Something magical happens when a group of my work comes together. The Kleins in Tesuque are wonderful people; they built a new house and have some works of mine that they wanted my input on hanging. What came to mind was introducing six yellow pieces that were from about 1970–74 in the three consecutive rooms, that were then woven in with works that they had already owned, some from the ’90s and earlier periods. I know that about my work—one and one equals three and one and two equals six—there’s this kind of exponential leaping. It could be just an awareness of some weird sense of logic that comes out, the more material you have. Knowing that, I can also play with that and make it even richer.

In the Klein situation, you have these six yellows that weave in with another order. On some level, the installation (to use a horrible word) would be this weaving between my persona and their persona to create a kind of world. It’s not just visual—how to see the rooms as what they were intended for, and then to build on that and show artwork off to its best advantage. I mean, in some sense, I would think that an artist is really like what Plato might call a true philosopher: you can go to the limit of any and all disciplines.

ART21: Are there limits to art making—rules?

TUTTLE: You know, that first little piece—you can have the yellow without the black in it, or the yellow with the black in it. And at the moment, it has the yellow with the black in it. And I thought that would push it forward, in the sense of things emerge or are born; they’re pushed forward. Because yellow is the color of natural ambiguity, it can recede or come forward. That’s why it was used in Italian primitive paintings with gold. It was gold in that case, but yellow and gold work the same way.

These simple things that any child could do—these sort-of rules of art, like [John Keats’s] famous rule of negative capability, or whether it’s “To be or not to be”—that has so much energy. It doesn’t say anything, but it has so much energy in it that generations and generations of human beings have pondered it. In some sense, the best art—or the aim of the best art—is to just let it be. You know, we should just let things happen that want to happen, you know. It’s not about making something happen, but about allowing something to take place.

Installation view of Richard Tuttle: It’s A Room for 3 People at The Drawing Center, New York, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Structures, 2005. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: And the border between drawing and sculpture?

TUTTLE: How can someone have sculptural ideas? I can have an idea how to play a Mozart sonata; I can have an idea how to make baked potatoes. But a sculptural idea is different. It’s like a different mind, where (I suppose) we dig up some three-dimensional sense.

I also find, in the world at large, that there’s a battle about the existence of the third dimension. Many of the cultures that primarily use the two-dimensional look much more dominant than the ones who connected early on to the three-dimensional. And I myself find that the two-dimensional in a way is more “real.” In a culture like Japan, everything is on a two-dimensional plane; and it’s inexhaustible, this two-dimensional plane.

But we all have an ability to step back from our own language, for example, and treat it like it’s something outside of us, and we can teach it to other people. And we use that third dimension to take a distance. And a lot of the synthesis in our culture comes from the use of that third dimension.

One of the questions of the moment is: “Should we sustain that third dimension? What does it cost us?” It’s very weighty because we don’t really account for it, and there’s an intuitive element to it. A lot of the real innovations in mathematics come from intuiting in the third dimension. And in other cultures, where three dimensions isn’t the focus, once that’s been discovered, then they’re able to use it on the two-dimensional plane with greater efficiency than the ones who were already using it. Artists have always been involved in this kind of universal stuff. We wouldn’t have Giotto if artists didn’t think about, like, “Does the third dimension exist or doesn’t it?” Or “How can it be expressed, if it does?”

ART21: What is the connection you see between art and life?

TUTTLE: My beginnings were with the Betty Parsons group. One of the important elements in that vision was that art is life—all of life. Both in the making and the critiquing, there is all of life. And there has to be, because if you don’t have all of life, then how can you make anything that really has some importance? I abhor anything that I personally feel reduces the scope of art. There’s a division left over from the twentieth century, where certain people might think that art is something that is made outside of any personal expression. Joseph Albers or the Bauhaus—it’s really coolly detached. And then there’s the other kind, where it is full of personal expression. The personal expression side is great, but you can finally get an art that is just an expression of some twisted personal idiosyncrasy.

Installation view of Richard Tuttle: It’s A Room for 3 People at The Drawing Center, New York, 2004. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Structures, 2005. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

TUTTLE: Before I went to kindergarten, I really wanted to be an artist. Not that I knew what being an artist was, but on the first day of kindergarten, the teacher handed out the paper and the colored crayons. And I just connected in my brain that this was the first day of my life, and that going to school was the start of everything that was important to me. I remember the drawing, to this moment. I took a pencil and I just made this horizon line, and then I took the colored pencils and I made a rainbow there. And that was my drawing.

I looked over, and I saw that the other kindergarteners were doing their sun, with the rays of the sun, and drawing their flowers from the bottom of the page, and all of that. And I knew that my drawing was more, say, advanced or sophisticated, but I also knew that I had lost a kind of innocence—irretrievably—that they still retained. And so, I was a little bit pushed back—in a state of confusion. Then, when the teacher collected the drawings, mine was not put up as one that was highly valued. I had to adjust to that, and of course I did, but my respect for the teacher was forever erased.

But the story goes on. When I had my first show at the Betty Parsons Gallery, when I was twenty-three or so, I looked over on the wall and saw a piece called Hill. And it was kind of the same rainbow that the graphite line had changed into. It was a big, startling moment to me. Because that really was the first day of my life, in a way, and quite a way from kindergarten—which I had mistakenly thought was the first day—to my show in a New York gallery.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2005 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.