Interview

Gumby, Vavoom, and Baseball Players

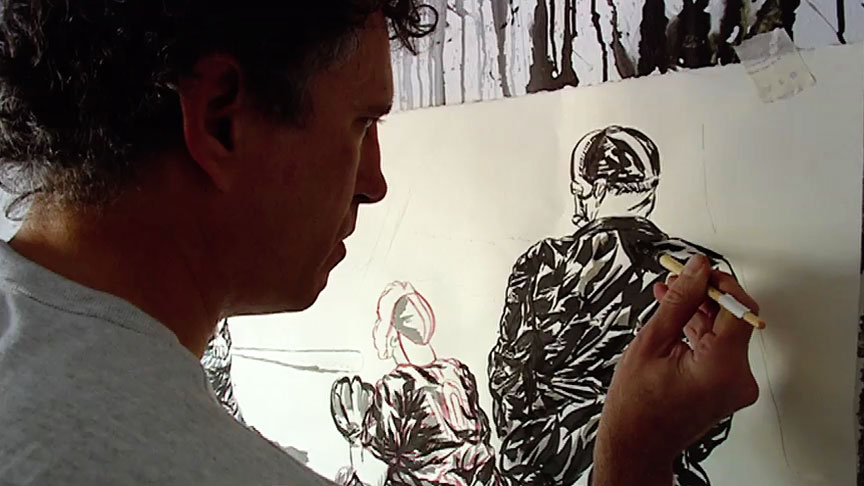

Raymond Pettibon in his studio, Hermosa Beach, California, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Artist Raymond Pettibon discusses his interest baseball, and the roles that various characters take on in his work.

ART21: Are any of the characters in your work ever heroes? Say, the baseball players…

PETTIBON: I’m not in awe of what most people would consider heroes, which would be someone of stature and power. In fact, those would tend to be people who I don’t respect at all. The public has a kind of natural awe of them that tends to be a mixture of fear, control, and violence. You could say the loss of innocence in baseball began with the fixing of the games in 1919, with the Black Sox World Series scandal.

Players—they all can’t live up to be a perfect model hero like Steve Garvey, who had an elementary school named after him. But that actually isn’t a good example because he had some pretty major scandals himself. But there’s something about athletes . . . and even horse racing. Horses are athletes, of sorts, too. They can have a heroic stature to me. People usually tend to value an extreme, one thing or another, whether it’s the intellectual against the athletic. Like, the jocks never mix with artists or the people who are studying physics. I admire both, but in a moral sense. I don’t have any expectation for anyone other than behaving decently to other people. That’s really not the true definition of a hero, though.

The heroic has an epic scale to it. If you look at my baseball works, for instance, there is a kind of larger than life attitude to a lot of it. But then, not all the works are a pure adulation of the ball players. I mean, they go into some pretty sordid avenues. My drawings dwell on that subject quite often as well.

ART21: You seem to like to mix the underbelly and the philosophy.

PETTIBON: Not always, though, and not always in the same drawing. You can look at a lot of my baseball drawings, and they don’t have that kind of a resentment of most figures—that you just automatically want to take them down a notch. There are quite a few that aren’t like that.

Raymond Pettibon in his studio, Hermosa Beach, California, 2003. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Humor. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: How far back does your interest in baseball go?

PETTIBON: Baseball has probably been my favorite since I was a child. Some of the others—like horse racing, that came in later, but football, basketball, track and field—I’m not obsessed with any of those. The reason why I keep coming back to certain images is, probably most often, that there’s a visual quality that works for me, and that can be as simple as drawing horse races.

I think, whether you are throwing the pitch or batting the ball, you do have that sense of movement. And for an artist like myself—whose work is about that one moment—that can be a reason I do that. But sports, and baseball in particular in America—there’s a lot more to it. There’s a lot more nuances, not just in the game itself, but that’s also important, too. My work on the subject does tap into some of the nuances of the game—the pitching of the baseball, for instance, or hitting a baseball—but also it says a lot about what goes on off the field as well about the society in general. It’s kind of a microcosm of the society as a whole.

ART21: It’s rare that an artist gives equal attention to both words and pictures. Could you have accomplished what you wanted as a writer?

PETTIBON: Yes, if I had to choose. But the point is: I don’t. I mean, I don’t feel I’m diluting what I’m saying by doing them both. I’m not trespassing on one or the other. To me, it’s natural. I don’t feel cheated. But on the other hand, I spend a lot more time writing than I do drawing. I really wouldn’t want to make that distinction or feel the need to separate the two or make excuses. The fact is, I make work that requires both, except in rare, rare cases.

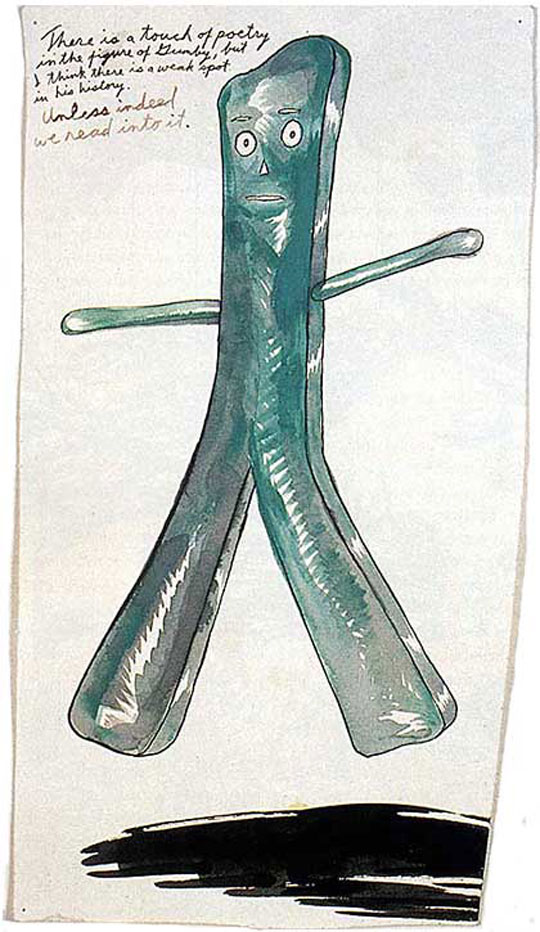

Raymond Pettibon. No title (There is a touch of poetry…), 1997–2001. Ink and watercolor on paper; 16 3/4 × 8 1/2 inches. Collection of Zoe and Joel Dictrow, New York. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

ART21: Can we talk about the Gumby theme in your work?

PETTIBON: Gumby? To put it in general terms, you’ll see in my work this tendency to take on some very ridiculous subject. Possibly you can look at it as being so far out there as to be, kind of, just a stray thought. Going back to the heroic figures, you can speak about a wider area of things that happen that puts the responsibility on the shoulders of something like Gumby. It’s not done in any sarcastic way. It’s not even meant to call attention to itself. All I’m really asking is for you to look at that with the same kind of respect that you would if it was some important historical figure or Greek statue. Or the usual subject matters that artists tend to use.

There’s also a reason why Gumby in particular works for me so well. Because it does relate to the way I make work, which has very much to do with words and reading in particular. Gumby is a kind of metaphor for how I work. He actually goes into the book, goes into a biography or historical book, and interacts with real figures from the past, and he becomes part of it. He brings it to another direction. And I tend to do that in my work. That’s why Gumby is a particularly important figure to me. I have to give credit to the figure of Gumby himself because it’s not something that I’m raising up by his bootstraps and putting in this high-art realm. Gumby’s creator, Art Clokey, was a pretty brilliant guy, and it wasn’t like the original Gumby cartoons weren’t worth paying attention to and that I’m rescuing him from Saturday morning children’s cartoons.

ART21: Is Gumby like an alter ego?

PETTIBON: Gumby represents an alter ego for my work as an artist. He represents me as an alter ego. There’s actually a lot more to that figure than just ninety-eight ounces of clay or whatever. Art Clokey was into Zen Buddhism and into a lot of pretty deep stuff for Saturday morning cartoons. Clokey was a pretty hip figure in Los Angeles and in the counterculture of the ’60s and the ’50s—the beatniks and the hippies. I have a lot of respect and affection for him, and for Pokey as well, and Goo, Prickle, and even the Blockheads. One other thing that I’ve never thought of—that Gumby does for me in some of his cartoons—is he goes into a biography or historical book and he interacts with real figures from the past: George Washington or whatever. And I tend to do that in my work and in my videos, as well.

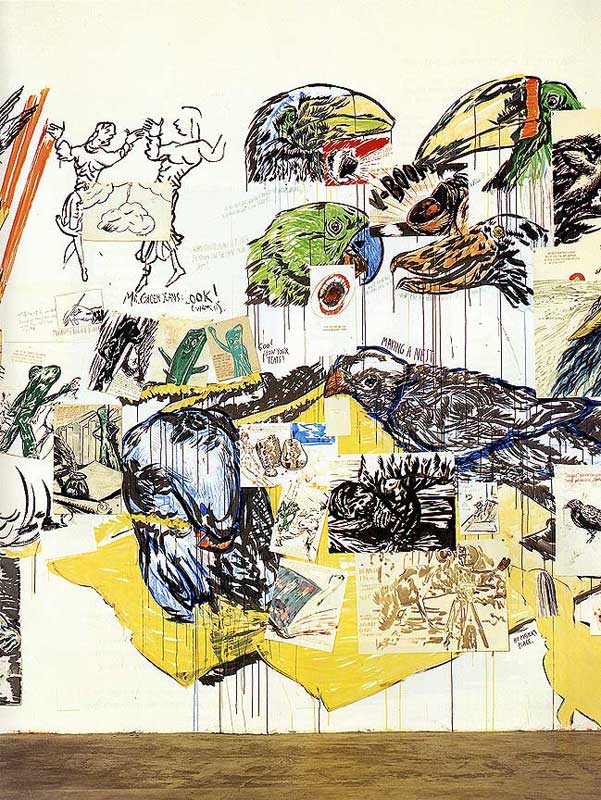

Raymond Pettibon. Installation view of Raymond Pettibon, at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, 2000. Photo by Joshua White. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

ART21: In some of the drawings, Gumby is paired with a vast landscape. It’s like one guy against the world.

PETTIBON: But you know who does more for me than Gumby? Vavoom. When I’m doing drawings of Vavoom, I create a situation of putting him in this epic, sublime, romantic landscape, and he is this little guy with a booming voice. It’s a perspective that has this panoramic scope to it.

ART21: When did these characters become part of your self or your repertoire?

PETTIBON: I don’t know the exact way that works. Usually there’s not any forethought. I don’t investigate and find the right character that is going to express the way I want to do things. But it starts, inevitably, with just one drawing. It resonates, and it keeps going from there. It snowballs into a persona that I keep going back to. But there isn’t any design to it. It establishes its own kind of momentum, and I don’t really have to consciously think about it.

I get asked a lot on this subject: “Why is that character so important to you?” And so forth. It’s not something that I thought was especially important the first time I did it. I may have drawn certain subjects numbers of times, but it doesn’t mean that I’m to this day obsessed with a character or dwell on it as the subject matter, or that I’m aching to get back to it as soon as possible. I feel that an artist has so much to see, and he just kind of works on. And you could probably say the same thing for just about any subject or profession, including, well, really anything.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.