Interview

“Groundswell” and Studio Works

Maya Lin in her Manhattan studio, New York, NY, 2000. Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 1 episode, "Identity," 2001. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Artist Maya Lin discusses her three-site installation piece, Groundswell (1993).

ART21: Tell us about Groundswell.

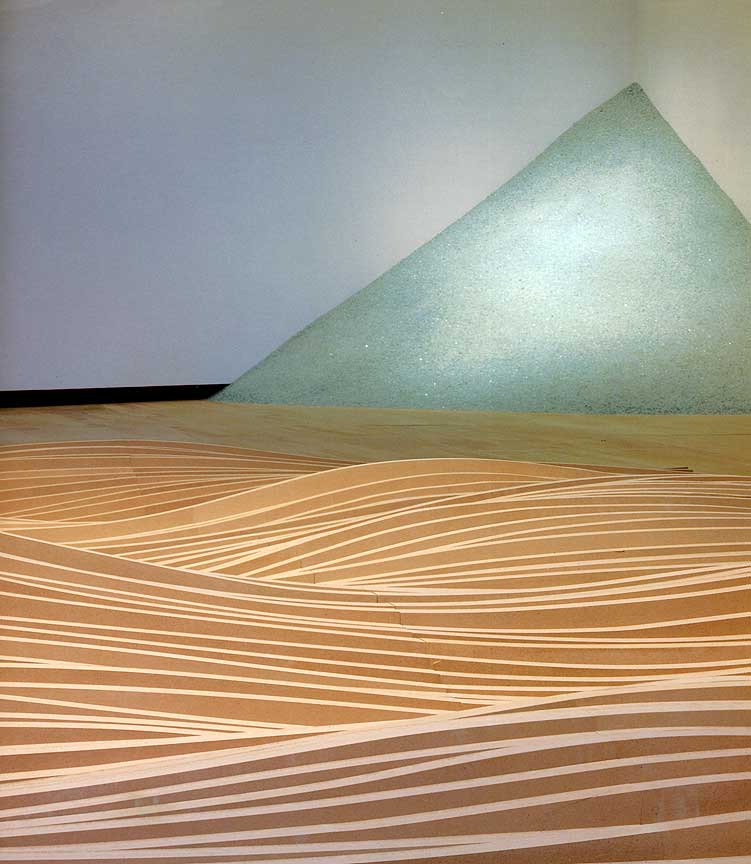

LIN: Groundswell is a piece that I made for the Wexner Center for the Arts. It would be their first permanent installation, and Sara Rogers, the curator at the Wexner Center at the time, had contacted me, as she was very aware of the smaller studio sculptures. I had been concurrently building the Civil Rights Memorial as I was making Topo and all these outdoor pieces. I was working in my studio. Some of the works were being shown with broken car glass, lead, beeswax. There were smaller, personally scaled works I could physically make myself. The rule was: I had to be able to make it. And I think Sara and I discussed the idea of bringing something of my studio works out of doors. And I was completely interested in doing that, knowing that it was a museum, knowing that—unlike a lot of art in outdoor places where you really have to almost gear yourself up for maintenance-free works—a work here could be more delicate. I took one look at the Wexner Center and I knew that. I had been for years wanting to use the broken glass out of doors, but inherently it’s still glass, and you just can’t touch it. You can’t put it out there for, just free, for everyday walkers-by.

So, when I visited the Wexner Center, I realized that, when Eisenmann designed the space, he had pretty much combined two disparate grids, and spaces were occurring naturally. They were what I would call his unplanned spaces, and they were occurring in very, very visible locations. At the front entrance, you looked out on this graveled rooftop. At the cafe, you looked down on an eight-foot-deep, very odd sort of pit, filling up with gum wrappers. And there was another one on the upper level where the administration was—highly visible but physically non-accessible, because each of these areas was walled off. It was something that you could look out on, both from inside and outside the building. And I knew right away that I could use broken glass. But at the same time, what I was thinking of doing would require dump truck loads of broken car glass, which basically I had not really ever dealt with. I mean, I had taken something that was, like—these pieces I was making inside were no longer than the size of a table. They were very, very small. But I knew that I wanted to do this.

The other thing that was very important to me was that—unlike the intense amount of planning, modeling, preparing that I go into to make some of the large-scale outdoor works—I wanted to bring to this piece more the act of spontaneously making the work of art. Which meant all that I actually did as drawings and planning was two or three very rough sketches on Xeroxes of the photographs of the existing place. I deliberately wanted to treat it the way I go into my studio, not knowing what I’m going to do, and make something. And inherently, the difference—when an artist literally has a blueprint for an idea and then lets other people build it, or whether you can actually at a larger scale physically go out and spontaneously make something—is something I really wanted to explore in this piece.

So, on a given day, forty-three tons of car glass arrived. I had a crew of three people, and we just made this piece. I was terrified because I also realized, “Well, if it’s an absolute disaster, I’m out there in full view.” A studio’s a wonderful place, because if it doesn’t work, nobody can ever hear about it. Here I was, with school groups coming by, watching this, and I’m out there not having a clue as to what I might want to do. It took me three or four days. And the way in which the glass was carried in . . . The architect in me kicked in, at some point earlier in the process, and I realized, “This is no different from getting roofing gravel up to the top of a roof.” So, I called up a roofing contractor, and I said, “Well, I’ve got these three rooftops that I need re-graveled,” and they were, like, “No problem.” Then I told them it was broken glass, and they said, “Slightly no problem.” And the wonderful thing about it is—to get all that gravel up, you need a boom crane and a conical bucket—and we dropped the glass, bucket load by bucket load.

And I knew that the piece would be about that because, again, these works are also about process. I think I’m absolutely coming out of a ’70s attitude in art, where the process of the making of the piece oftentimes can play into the piece. And for this, it is about a meeting of East and West. It’s a play on the Japanese raked gardens of Kyoto, as well as the Indian burial and effigy mounds of Athens, Ohio. So, it’s a real blend.

Maya Lin. The Wave Field, 1995. Shaped earth; 100 × 100 feet. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

ART21: Could you talk a little more about these references?

LIN: The Wexner Center is in Columbus, Ohio. It’s forty minutes away from Mound City, which is the largest grouping of these mounds. So, it’s a melding of a conscious idea on my part to sort of blend East/West culture, but it’s also about bringing a studio artwork mentality out of doors. And also it’s about process. And I think [Robert] Smithson had done a piece for Kent State, called Asphalt Pour, in the ’70s. He took a dump truck full of asphalt and just dumped it on the side of a hill. And I think he buried a shed with it (or was that another artist?). It was just about bringing in—tying in—a spontaneous process into the piece. But for me, it was my first artwork that I made that I was having a problem. Because I knew when I had done the monuments that I was still searching for something. I really do feel the memorials are separate—[that they] stand apart. I think monuments, unlike artworks, are a blending of art and architecture. They have a function, but their function is for the most part purely symbolic, so they’re in between. They’re sort of the true hybrid between art and architecture.

I knew, for me, that I was struggling in the studio works—and in an earlier piece called Topo—to get back to the land in a much more fluid yet intuitive way. And I think, when I had made Groundswell, I realized that, for me, it was my first artwork, and I knew that I was very interested in where it was going to go. And where it went was to The Wave Field, which again led me to the whole Topologies show. So I think, for me, my sculptures deal with naturally occurring phenomena, and they’re embedded and very closely aligned with geology and landscape and natural earth formations. I think that someone’s work—like Alice Aycock or Scott Burton’s work—dealt with a language that tied it back into architecture.

ART21: Why is there such a distinction in your thinking between art and architecture?

LIN: I actually I keep them separate; that’s just a choice I made. I don’t know why I did it. I felt compelled to do it, basically. I have two sides: creativity and the architecture. It’s got ideas about framing the landscape, being ecologically and environmentally sensitive—not that a lot of the artworks aren’t using recycled materials and about nature in another way. But formally, I liked that they’re different, that I don’t want my architecture looking like my sculptures, and I don’t want the sculptures being at all architectonic in their form. And that’s just a choice I made, or a choice that was made. I don’t think I ever really thought about it. I don’t think I woke up one day and said, “I’m going to be an artist on some days and . . .” It was more that I couldn’t choose between the two, nor did I choose to blend them. I think it’s taken me a body of work to see how I am developing.

Maya Lin. Avalanche, 1997. Tempered glass; 10 × 19 × 21 feet. Installation at the South Eastern Center for Contemporary Art, Winston-Salem, North Carlina. Photo by Jackson Smith. Courtesy of the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art and Gagosian Gallery, New York.

ART21: Can you talk some more about this?

LIN: Okay. I think there’s a very easy segue into it, which I think is very, very interesting. I have one huge concern because I sort of split my time between the artworks and the architecture that—in a way, the processes of making them are very, very different. And I’ve always been afraid that there’d be a real split, or a schizophrenia that would begin to occur, between my life and my creative process as an architect and my life in art.

Concurrent to the Topologies show, I had been asked by Knoll, a furniture company, to design their sixtieth anniversary collection. And from a designer’s point of view, from the design/architectural world, the chair is, in a way, the closest to a self-portrait. What do you look like, if you were a chair? And that was a very tough struggle for me, because I just was searching and searching for something. And I started researching the history of the chair. And what I came up with is something I ended up titling Stones, and they are as much about sculpture as they are about design and architecture. And the form is . . . you can’t quite tell. It’s a very simple elliptical stool that you sit on—ever so slightly concave in the center. They’re lightweight concrete. And they are about that merger, or that dialogue, I have between art and design; they’re a hybrid.

And the whole series is called The Earth Is (Not Flat); they deal with the curvature of the Earth. There’s a chaise lounge called Longitude, which literally is the same inspiration I had to make The Wave Field. It’s a slight undulation in the ground plan. But it also is playing off of design, taking Mies van der Rohe’s classic psychiatrist flat daybed and literally throwing a curve onto that, from a design point of view. I think, for me, the Stones are my favorite, if you can have favorites (it’s always terrible to say your favorite).

But because, in their simplicity, they both talk to the sculptural world and the architectural world, and in that sense they really talk about who I am and where I’m coming from, they’re very important to me. So that, simultaneously, I could be doing an art show called Topologies and a commercial line of furniture entitled The Earth Is (Not Flat), and yet they’re the same voice. For the first time, and that was a couple of years ago, I was sort of made to feel whole. But I think it is hard to separate yourself into two worlds. So, it’s very nice when you know that the worlds, though separate, are in absolute close dialogue, and that they’re in step with one another. And that’s been very, very important for me in my aesthetic, artistic development.