Teaching with Contemporary Art

Materials + Environmentalism

Students created quadrants of different sections of the beach to collect data on how many nurdles there were. Courtesy of Birra-Li Ward.

“Technology is not neutral. We’re inside of what we make, and it’s inside of us. We’re living in a world of connections—and it matters which ones get made and unmade.” – Donna Haraway

We are connected locally and globally and share a desire to innovate for the future, so how does learning impact our local environment now and in the future? The action we can take is through our material choices in the classroom and by using art and art making as tools for environmental advocacy.

In education, teachers carefully consider and look to utilize contemporary artists to explore ways to embrace and to teach the value of the creative process, with the goal of students learning to reflect and to make connections to further understand themselves and the world. We cherish this; it is what matters in education. We invest in the time we have and when it all seems to work and we feel and see true moments of learning, it brings us joy and a sigh of accomplishment.

Students worked together to try and come up with the design for their collaborative artwork. Courtesy of Birra-Li Ward.

The footprint and environmental impacts that these moments might have are at times a sad reminder (in my perspective). What cost might these moments incur? As educators, we have a responsibility to engage with young people, fostering their curiosity and guiding them toward solutions.

Contemporary art can help us to be more present in our world and see both current and future possibilities that we can easily miss. Artist Mary Mattingly speaks of “inventing a world that was perverse” and then shifting to one where we “all had to live” in. This envisioned future is not escapist or fantasy, nor is it eco-anxiety inducing. Mattingly’s work acts as a symbol and demonstration of how collaboration, community and collective acts can help realise that other ways of being and living are possible. This approach seems fitting to share with our students.

Living Landscapes. Students created these to test decomposition of natural materials labelled as biodegradable. Courtesy of Birra-Li Ward.

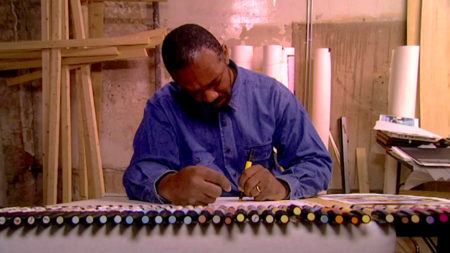

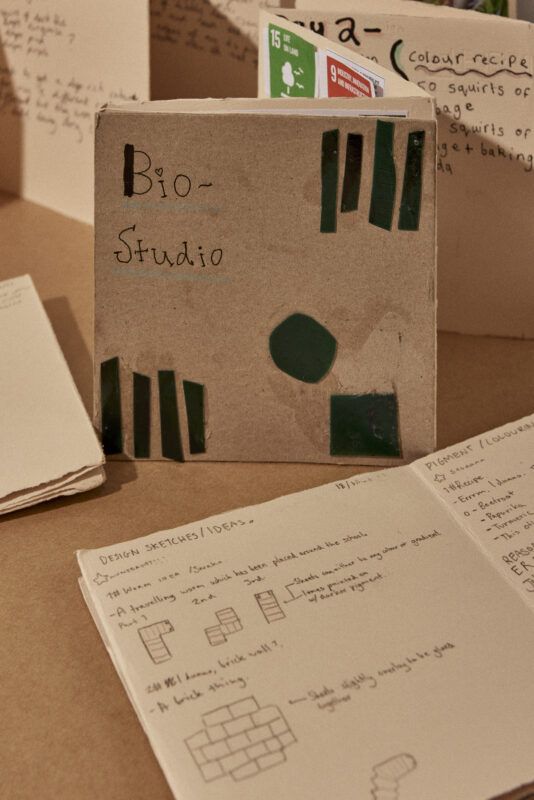

If our impact is greater when we work together, a common practice with contemporary artists, so too should we be doing this as learners and educators. Recently, I began collaborating and learning with the STEAM (STEM) teacher at my school. This acronym stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts & Mathematics. In my context, STEAM teaching focuses on solutions and processes using an integration of the mentioned areas. There is a discourse that surrounds the title of such a subject, but it becomes somewhat peripheral when an authentic exchange occurs between teachers, and we ignore the silos arranged by a system. This collaboration led to the creation of a unit of work, and now a subject, titled Bio-studio that was inspired as we went through the course by the student-generated questions and directions that they wanted to take.

A hybrid of a science and art journal were created. © Michael Pham.

Bio-studio uses the “UN Sustainability Goal #14: Life Below Water” as a constant pivot point. This goal is not only relevant, but it is real now and part of our future. Interviewing students prior to their involvement showed that over half were not connected to the UN sustainability goals; they didn’t know what the goals were or, if they did, they were not applying them outside of the classroom in which they had heard about them. These goals are a way to connect students to their sustainability values and their learning and to the real-world environmental issues that we all are facing when applied in a tangible way. My colleague, Sarah, and I had positive feedback from the students. One student noted that, “Before the Bio-studio project, I had no idea what the UN sustainability goals even were. Through the project we learned about what they were, and how the UN continues to work towards them. This is knowledge I still use often in discussions around the environment and its future.”

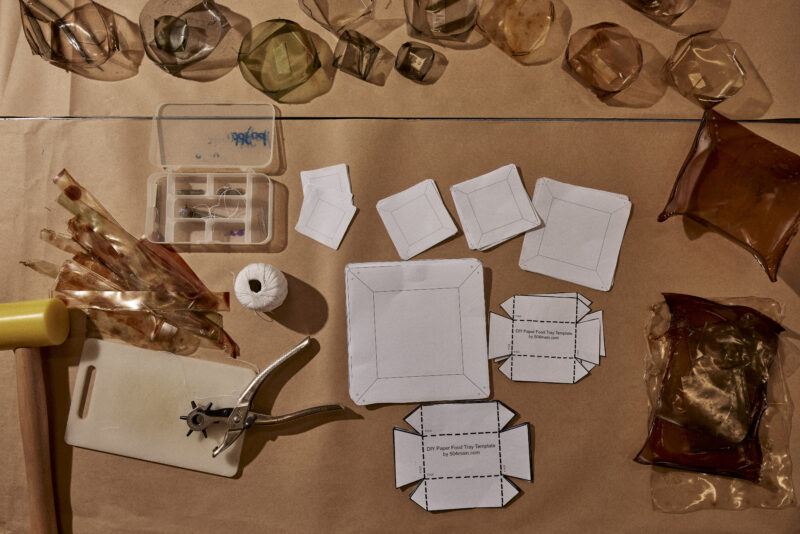

Using alginate to create nurdle mimicry to prove how hard it is for fish and birds to tell the difference between fish eggs and nurdles. © Michael Pham.

Goal #14 can be used to explore Mattingly’s Ebb of a Spring Tide. This installation follows Mattingly’s ongoing relationship with water. Ask students to consider where their water sources are and to reflect on the history and journey of the waters in your area and our ethical responsibilities and caretaking of these waters. In Bio-studio, students also undertook the role of being citizen scientists by sampling our local marine environment that was within walking distance to the school. The students collected data and undertook surveying techniques to learn about the damage occurring through plastic contamination of waterways, including nurdles, and keenly shared their data with local and global organisations. When recycled plastics are melted down they become pre-production pellets called nurdles. These are lightweight discs that are easily airborne and tend to end up in waterways. The solution has become part of the environmental problem associated with plastics. As a student from the program reflected, “It feels like something we could fix so easily, it’s just really sad to see we haven’t.”

Students presented their learning about saddle stitching with bioplastics in an expo. © Michael Pham.

Similarly to Mattingly, Jessie French, a Naarm (Melbourne, Australia) based scientist/artist, explores the possibilities of a “speculative post-petrochemical future” through using algae-based polymers in installations and functional plastics. French suggests there is greater potential in not defining roles and offers provocations for students to consider innovative solutions and to see the interconnectedness of science and art that have a real-world impact.

The collaborative artwork. © Michael Pham.

Over the course of Bio-studio, the students took heed of Mattingly’s and French’s practice and made a collaborative artwork using the bioplastics they had produced. The artwork used sustainable and renewable agar, glycerin (a biodegradable substance), and water. The bioplastic was coloured using locally sourced natural materials where possible. Students spoke of the Bio-studio program as an opportunity to learn more about the materials in our class–“I was able to explore the idea of sustainability further, as there is so little that we actually know works, but there’s so much more to experiment with.” Next semester, this artwork and the offcuts will be melted back down and there will be another iteration of learning with another group of students. Nothing will go to the landfill.

We need to prompt ourselves and our students to ask critical questions that will help to minimize the environmental impact and embed these in our minds: What sustainability issues arise from using certain materials, and what environmental residue do they have? Is the result worth the environmental cost?

Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (1991), pp.149-181.