Interview

Politics, Process, and Postmodernism

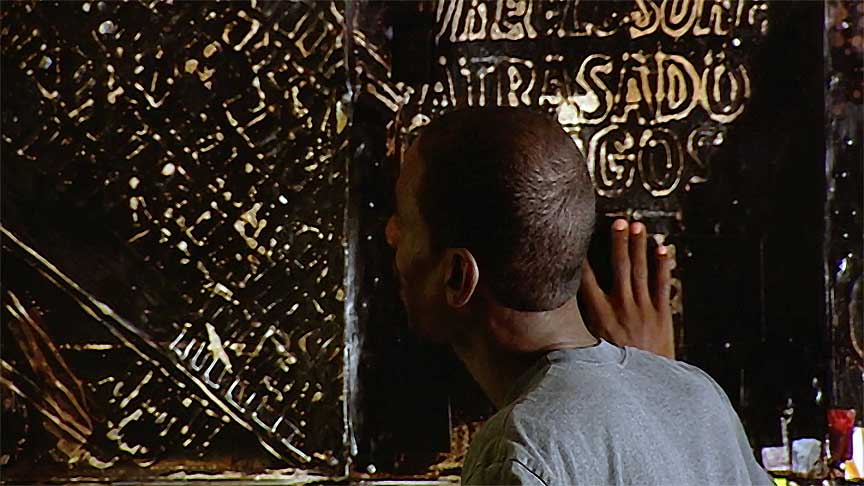

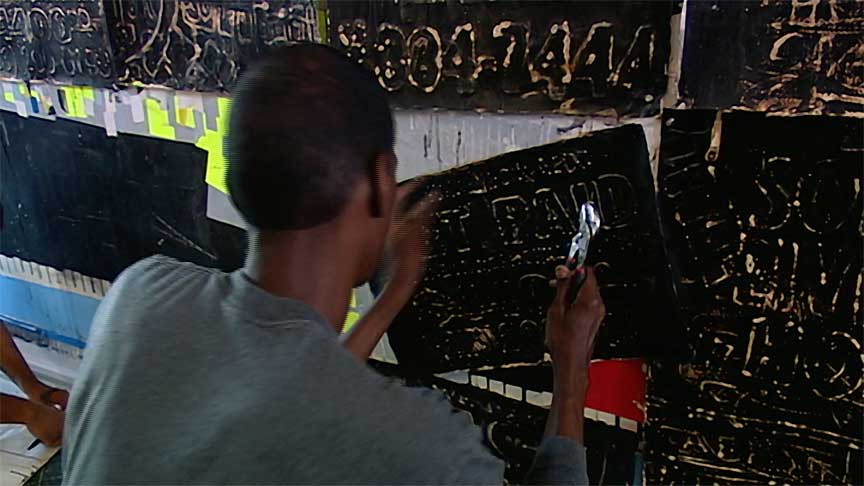

Mark Bradford in his studio, Los Angeles, CA, 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

Artist Mark Bradford discusses his process and sources of inspiration, as well as his work’s relation to politics and postmodernism.

ART21: Do you think of your work as political?

BRADFORD: An artist has a choice to be as political or apolitical as anyone else who’s making choices. So, I don’t think an artist is necessarily apolitical if he or she doesn’t make overtly political work. But so much of contemporary art is engaged in the ideas that are circulating in the atmosphere, in the press and the media, and oftentimes we’re influenced by that. So, it seems comfortable to me to have that bleed into my work. For me, the subtext is always political. You look at a sign and you realize it belongs to popular culture. But on another level, the sheer density of advertising creates a psychic mass, an overlay that can sometimes be very tense or aggressive. The colors shift; the palette becomes very violent. If there’s a twenty-foot wall with one advertisement for a movie about war, then you have the repetition of the same image over and over: war, violence, explosions, things being blown apart. As a citizen, you have to participate in that every day. You have to walk by until it’s changed.

ART21: Your mixed media collages, like Ridin’ Dirty, incorporate bits of found signage and advertising. Do you know other artists working in a similar way?

BRADFORD: Immediately my thoughts go to Robert Rauschenberg’s combines. What he was gathering was found. But it’s interesting because he found a lot of furniture, cans, and boxes—domestic throwaways. I think if you fast-forward to now, you would see less domestic and more media throwaways. I think if Rauschenberg were pulling from the streets now, he and I would be fighting for the billboards. (LAUGHS)

ART21: Is your process with the collages more additive or subtractive?

BRADFORD: My practice is décollage and collage at the same time. Décollage: I take it away; collage: I immediately add it right back. It’s almost like a rhythm. I’m a builder and a demolisher. I put up so I can tear down. I’m a speculator and a developer. In archaeological terms, I excavate and I build at the same time. As a child I actually wanted to be an archaeologist, so I would dig in my backyard. When I was six, I was convinced that I could probably find a dinosaur bone there, but after about a week I realized that it was only in particular places that you find dinosaur bones. It was not like my mother stopped me. She was very good about allowing me to do, as she called them, “projects.”

Mark Bradford in his studio, Los Angeles, CA, 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

ART21: Can you say more about these childhood projects and the influence your family had on your development as an artist?

BRADFORD: My art practice goes back to my childhood, but it’s not an art background. It’s a making background. I’ve always been a creator. My mother was a creator; my grandmother was a creator. They were seamstresses. There were always scraps of everything around. There were always two or three or four projects going on at the same time. We just never had an art word for it. But I would go to the museum as a child, and I was bored. They would tell me about art, and I would look around and say, “This is art.” Then I’d get on the bus and go home. It never touched me. But the projects at home touched me. For instance, making the signs for the prices at my mother’s hair salon: I was in charge of that, so I taught myself calligraphy. So, my very early work used signage and text, but it was not perfect. It always got a little slimmer at the end because I wouldn’t measure it properly. (LAUGHS) But it worked out. My mother always said, “When I raise the prices, you’ll have another chance.” (LAUGHS)

ART21: When was the shift from being a maker to being an artist?

BRADFORD: There wasn’t really a light-bulb moment at the shift from the idea of just making to the idea of being an artist. At CalArts, there was no shock, no “Oh, wow!” There was no “uh-huh” moment. But there were bodies of ideas, writings by people who were basically writing how I was born. I felt like I’d discovered friends in these books and writers, these revolutionary people. It was like a coming home to language, to people who were critiquing, questioning, remixing larger bodies of ideas. It was the reading, the writing, the written word—not so much visual art, photography, painting, sculpture. But the written word can be poured into any vessel. I do it now. It’s poured into video, into a painting, into a public-domain practice. It’s the idea that holds it together for me.

I never knew what the postmodern condition was before I went to art school. I never knew about Michel Foucault, bell hooks, Cornel West, or Henry Louis Gates, Jr. But even though I had never read those types of writings, I lived with people who were living those types of lives. I remember coming home and telling my mother, “You know, you’re postmodern.” She’d say, “Oh, that’s sweet.”

Mark Bradford in his studio, Los Angeles, CA, 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

ART21: What did learning about these things, such as the postmodern condition, mean to you at the time?

BRADFORD: When I started thinking and reading about the postmodern condition—or fluidity—I saw it as taking independence. It was revolutionary for me that you could put things together based on your desire for them to be together. Not because they were politically correct, not because they are culturally comfortable or sociologically safe, but because you decide they’re together. If you decide those tennis shoes and those polka-dot socks are together, they’re together because you say so. I had always done that, but I was aware that it wasn’t always the “right” thing to do—not because I didn’t feel it was right, but because I was made aware by some people (in society, say, or in school) that that behavior was not correct. So, my mother and I would go to the store, and I’d get a G.I. Joe and a Barbie, and I’d bring them to school when we had Show and Tell. “So, which one is yours?” said the teacher. “Both,” I said. “Well, that’s not going to work,” she said. “Why not,” I asked. And she answered, “Well, what does your mother think about this?” I was always supported in the domestic realm, and I was always strong about standing up for myself, but there were still struggles in my life. Reading about these kinds of conditions made me realize it was about independence, about doing your own thing. And that’s a state of mind. It’s not an artwork or a book. It’s a state of mind. Fluidity, juxtapositions, cultural borrowing—they’ve all been going on for centuries. The only authenticity there is what I put together.

I take comfort in histories and knowing that something came before me and something will come after me and that I’m just part of it. Sometimes students will say, “Well, it’s all been done.” But I think, “Who cares? What does that have to do with anything?” I wouldn’t be painting if I cared about that. Okay, it’s all been done—so what? You have to figure out how to do it for you.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2007 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.