Interview

“Market>Place”

Mark Bradford. Market>Place, 2006. Installation view at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

Artist Mark Bradford discusses his 2006 installation Market>Place.

ART21: What was the inspiration behind your installation, Market >Place?

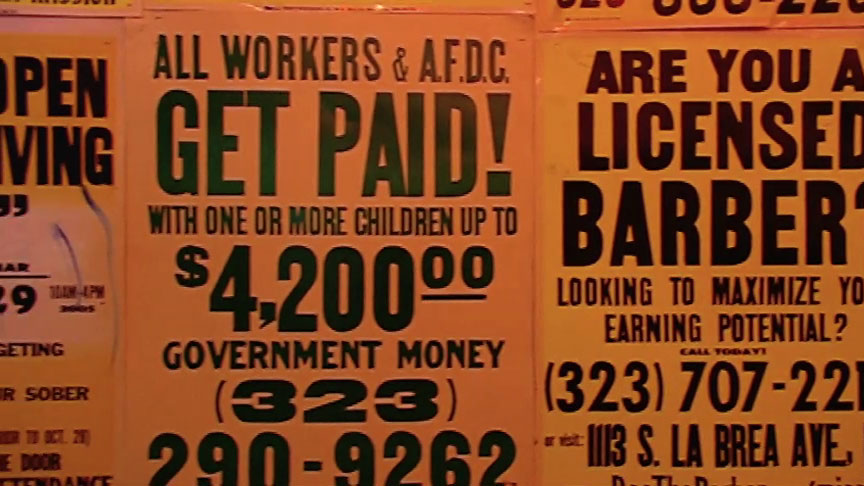

BRADFORD: In Market >Place, I wanted to create an environment that had something to do with trade, with public space, and the way people use it for pleasure, for business, for meetings, for secrets. I like that. And this was the amalgamation of all that put together. I mean, you have “100% Roaches Gone” next to “Are You A Licensed Barber?” next to “Lifetime Hair, 100% Virgin Indian Hair,” “All Workers AFDC Get Paid.”

What’s interesting about signage is that it’s about the conditions at a particular location. Informal advertising has always been around. But it just exploded in 1992 after the civil unrest in Los Angeles, when buildings were burned down and demolished. The riots cleared the land; they created huge open spaces. Because the memory of what cleared the space was violent, people made barricades. They put up cyclone fencing or plywood, so it felt like a walled city. You had all these interiors, and peripherals, with memories of something. Memory still inhabited the land, but there was nothing there. But there was all this free advertising space, and that’s when you saw explosions of informal advertising, sort of like parasitic systems, coming and laying on top of these spaces.

ART21: You decided to co-opt this and build it into your work?

BRADFORD: Early on, I was interested in using material that came from my merchant roots. My mother was a hair stylist; I was a hair stylist. But then I started thinking, “Where is what I do?” It doesn’t sound right, but that was my question. And the answer to “where?” was “community.” Once I looked out of the hair salon and became interested in the environment around me—and the language of that environment—everything that I had been trying to talk about was already there, speaking and having dialogues. I wanted to engage that material more directly. The conversations I was interested in were about community, fluidity—about a merchant dynamic and the details that point to a genus of change. The species I use sometimes are racial, sexual, cultural, stereotypical. But the genus I’m always interested in is change.

Mark Bradford. Market>Place, 2006. Installation view at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

ART21: Did your experience working in the hair salon inform the work?

BRADFORD: It’s really interesting coming from a merchant family because you learn things through merchant culture. For instance, we had a hair salon out on Washington and Western, and next door to us was a Latin family, Jeanie and Horatio, who sold mattresses. Next door to them was a Nigerian (I think his name was Ali) who sold things from Nigeria. Next door to that was a Chinese man who sold used televisions. And so, this palimpsest of cultures all circulated around trade. The thing I learned the most from being in that environment is how everything overlaps and intersects each other.

ART21: How difficult was it to work during the Los Angeles riots of 1992?

BRADFORD: In the media they only showed the negative. During the riots, they didn’t show the Koreans and the blacks working together to save their businesses, as we did. Two doors down from us, there was a Korean family that owned a hair salon, and we were going back and forth with supplies after the curfew. We really weren’t supposed to be working. Everything shut down at six o’clock after the civil unrest. There were no stores; there was a curfew imposed. Well, to merchants, six o’clock was just not going to work. For a hair stylist who had a lot of customers coming in after six o’clock, that just wasn’t going to happen. So, what a lot of people did was put up black curtains, or they didn’t open the shutters, and business continued. Every business was still open, but it became this invisible economy.

ART21: Was this experience in some way the impetus for Market >Place?

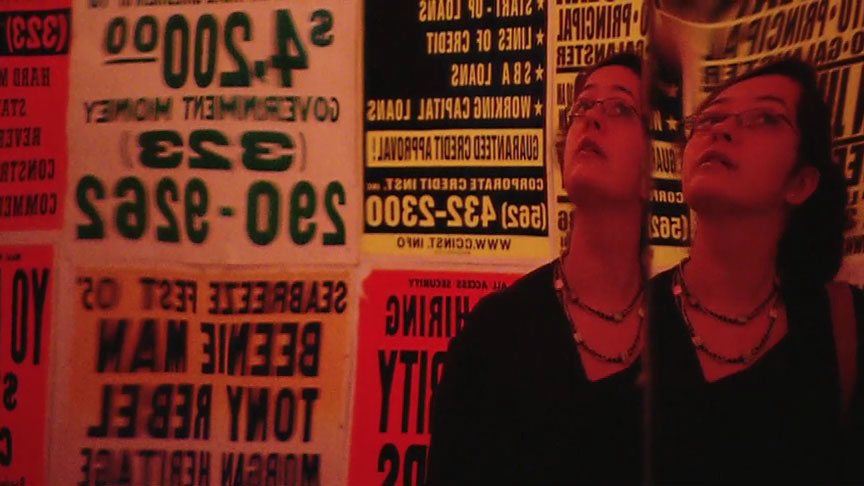

BRADFORD: I wanted to create the feeling of being outdoors and indoors at the same time—those little passageways, alleyways, or narrow spaces between buildings that people turn into private places to talk and gather in. It was metaphoric, almost like a funhouse. I wanted to create a saturation—and reflections and memory of things you thought you saw that weren’t quite clear—which to me is what happens when you’re in a public environment or walking down the street. If you relate the story back, it’s going to be about memories that layer on top of each other, reflect each other, and about conversations between the two.

I’m like a modern-day flâneur. I like to walk through the city and find details and then abstract them and make them my own. I’m not speaking for a community or trying to make a sociopolitical point. At the end, it’s my mapping, my subjectivity.

Mark Bradford. Market>Place, 2006. Installation view at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

ART21: What is your goal in filming? How do you decide on the posters?

BRADFORD: The goal of the filming is a certain essence that I’m trying to capture. The posters are always merchant posters. I don’t collect all posters. I generally collect merchant posters because they talk about a service, and the service talks about a body, and that body talks about a community, and that community talks about many different conversations.

ART21: And the posters are also connected to your interest in public space?

BRADFORD: I scan when I’m walking. Maybe it’s about mapping or tracing the ghost of cities past. It’s the pulling off of a layer and finding another underneath. It’s the reference and the details that point to people saying, “We exist; we were here.” It’s like excavating Rome and finding there was another Rome underneath. That’s what I find interesting about public space.

Graffiti is interesting to me because it’s in the public domain but it’s full of secrets, and unless you’re part of that system, you can’t unlock those secrets. I can see it for its shapes, its forms, but I don’t understand it. Another person will say, “Oh, you can’t read that?” And he’ll tell me this means this; that means that. It’s all the interconnected secrets and overlays that I really find interesting in public space. I guess I keep talking about that. Why not private space? Because private space is private, and public space has the potential to be inclusive. It’s the difference between instant messaging on the computer and going to a café or bar to meet and talk. When you’re home, you’re behind closed doors. That’s another kind of conversation.

Mark Bradford. Market>Place, 2006. Installation view at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), 2006. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Paradox. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

ART21: Is the relationship between public and private important to you in your work?

BRADFORD: I see the relationship between public and private over and over in my work. It’s not something I set out to do. I take a lot of information from the public sector. Then I go to my very private studio and I make something that exists between the two. Maybe it has a lot to do with me as a person. I’m in a very public body: six-feet-eight is very public, and I don’t have much privacy when I’m out. At any moment, someone will just tap me on the shoulder and say, “Excuse me . . . uh . . . how tall are you?” So, I’ve always been aware of that relationship between public and private in regard to my body. And I’m sure that it bleeds into the work.

ART21: And how we experience public and private moments has a lot do with language, with how we communicate them to others . . .

BRADFORD: Recently, there was a lot of language from civil rights used in the immigration rally, where 500,000 people took over downtown Los Angeles. Many people used Martin Luther King’s “We Shall Overcome.” I don’t know if people talked about it. I don’t even know if it was in the news, but you actually saw a sort of borrowing and palimpsest. I’m comfortable with palimpsest, which is the layering and layering of texts. It’s an old term. I don’t think it’s used that much anymore, but monks would write on papyrus and, because they didn’t have a lot of papyrus, they would rub it out and put another text on top. But many times, the text that they rubbed out didn’t rub out completely, so you had these layers upon layers of text, which is really interesting to me.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2007 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.