Interview

Heroines and Working in the Community

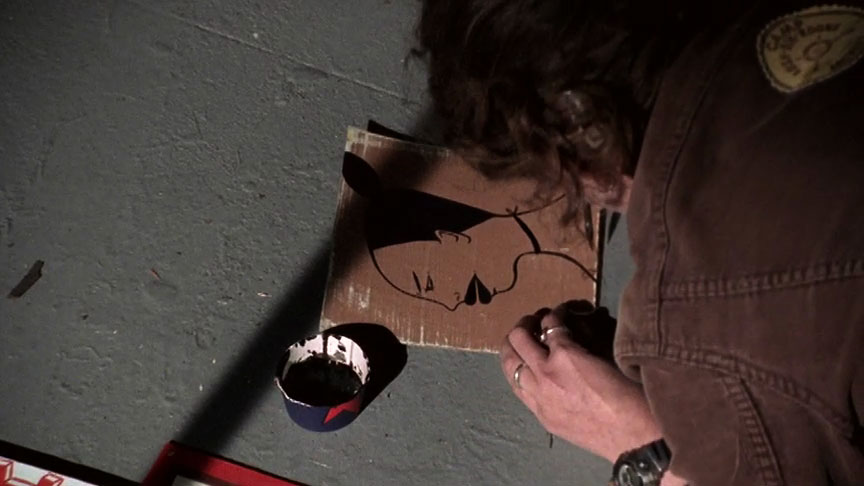

Margaret Kilgallen in her studio, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Margaret Kilgallen discusses her process, and her personal connections to the heroines featured in her work.

ART21: Could we talk a little about your process? Especially the difference between doing work indoors, in a gallery or museum setting, and outdoors, in the train yard or graffiti on a building.

KILGALLEN: I think there’s an attitude difference between what’s done inside and what’s done outdoors. Your audience is different, so if you’re working outside on the trains, you’re working for a specific audience that looks at those things, like, especially other people who ride on trains and who are interested in train history and folklore. And if you’re doing something in the city, then hopefully you’re speaking to somebody who has an open mind who is walking by. And you’re also speaking to a community of other people who do similar types of work. I like to think that the outdoor community is broad and able and open for anybody to see. And often, if you do work for a gallery or an inside location, your audience is narrowed just by the location and what kind of a place it is. A museum probably gets more people, a wider range of people, than a commercial gallery.

ART21: And you’ve also done community-based work, involving people from the community?

KILGALLEN: I worked on a mural project at the Marin Headlands with a group of kids from Marin City. I think there were about twelve of them. And it was a group of kids who were selected from an afterschool program, who were interested in painting and interested in art and interested in making a mural. And so, those kids came over to the Marin Headlands, and we went on a hike with a person who worked at the nursery at Marin Headlands. We went and looked at wild flowers and plants, and then the kids all chose one that they could paint. And so, I didn’t paint on the mural at all; the kids did all the work. And they, a lot of them, were not interested in going on a hike, at all. They were scared of bugs and scared of grass and leaves; and anytime something moved, somebody would scream. But it was really, really fun to work with them because, with just a little bit of prodding, they were really excited about it. And it was kind of funny, too, because I would walk in, and I would say “Hi!” to everybody, and they would just sit back and not make any facial expression at all—they would just act all tough. And then, as I got to know them, they got rowdier and rowdier and more outgoing. It was fun.

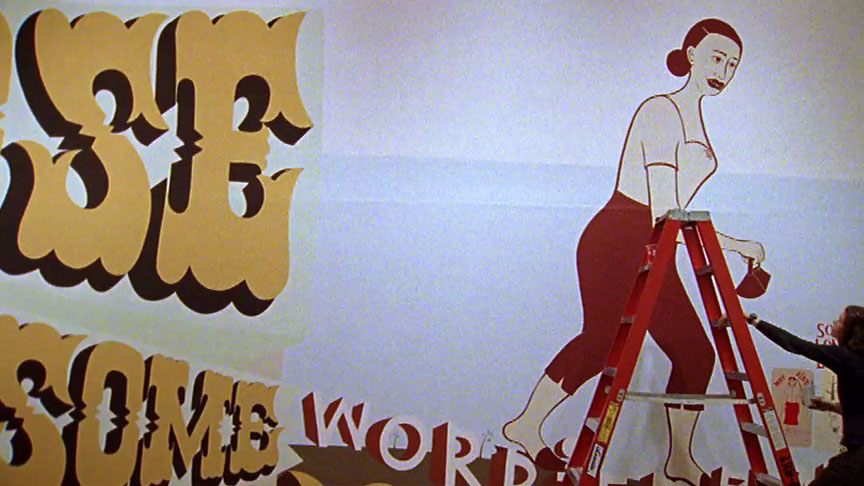

Margaret Kilgallen installing work at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, Place. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

ART21: In a lot of your paintings, there are figures, which seem to be heroes or, rather, heroines. Who are these women, and what do they mean to you?

KILGALLEN: I want to say one more thing about the community art. I guess the reason I’m interested in doing community-related things is that I feel that the more and more work I do in a gallery, it is really easy to get separated from people. As an artist, you want to be able to sell your work, and you want to be able to live off your work, and the world that involves the art buying and selling is a very closed world. And sometimes you forget about the other world around you. Doing community art sort of keeps you in touch with where you’re from—where I’m from.

ART21: Establishing or maintaining connections seems to be a large part of your work, whether it’s with a community, people who make things by hand, or with other women.

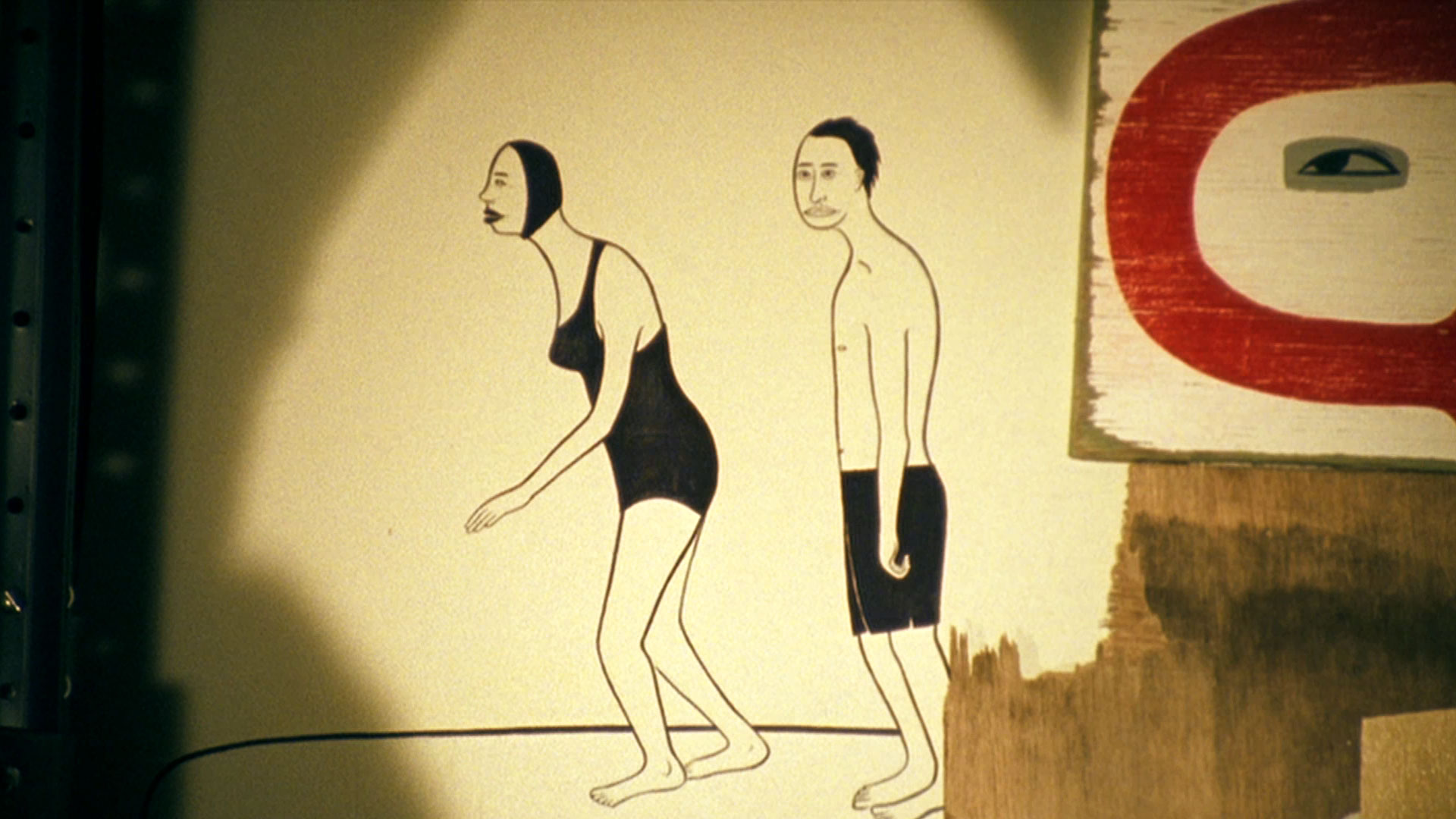

KILGALLEN: I do paint a lot of women, and I do have a lot of heroines as well as a lot of heroes, too. But I definitely paint more women, and I think maybe it’s because I’m a woman. I like to paint images of women whom I find inspiring. And in the beginning, I used to (and I still do) hear somebody playing music on a record. And then, I wouldn’t know what they looked like at all, but I would imagine what they looked like and draw it. Or, I would read something in a book. Like, I used to read a lot about the history of swimming, and the first woman to win the Olympics in 1912 was a woman named Fanny Durack. Now, I’m hoping I’m right again, but her name was Fanny Durack, and she was from Australia, and she wore a full wool suit. And the reason she won is because she swam the Australian crawl, and the other women weren’t swimming that way. But I actually feel like a good portion of my heroes are living now and alive, and a lot of them I know.

Work by Margaret Kilgallen in her studio, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive episode, “Margaret Kilgallen: Heroines,” 2013. © Art21, Inc. 2013.

ART21: Would you like to name a few?

KILGALLEN: Should I give you a list or something?

ART21: Maybe an example or two.

KILGALLEN: Matokie Slaughter—she’s an old-time banjo player. Algia Mae Hinton—she plays kind of bluesy guitar and does flat-footing at the same time. Kathleen Hanna—she’s a rock star, about my age, probably. Gosh, I could think of more, but it’s going to take me a second.

Margaret Kilgallen in a Bay Area rail yard, CA, 2000. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive episode, “Margaret Kilgallen: Heroines,” 2013. © Art21, Inc. 2013.

ART21: I’m sure there are many strong women you could name, but you only seem to paint a few.

KILGALLEN: Well, like Matokie Slaughter, for instance—I got interested in old-time music, particularly the banjo, and the records I would buy would have no women on them, ever. And she was the first woman I ever saw on an old-time record; now, I know of other women who also do that and do that today. (And she’s still alive, too.) I couldn’t believe I had found a woman on there. And I didn’t know it was a woman for a while because of the name, Matokie. I didn’t know what gender that was, so I felt very excited about that. Algia Mae Hinton—I saw her on a tape all about flat-footing and buck dancing. She’s pretty old now, I think. She’s a single mother and supports her children by playing her music. And she was also the only woman in this sequence of that tape who was playing and dancing. And she would play her guitar, and she would do the flat-footing, and then she would turn around and put her guitar on her back and play the guitar and dance. It was pretty incredible. So, I don’t like to choose people that everybody knows; I like to choose people that just do small things and yet somehow hit me in my heart.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.