Teaching with Contemporary Art

Maps Providing a Sense of Direction

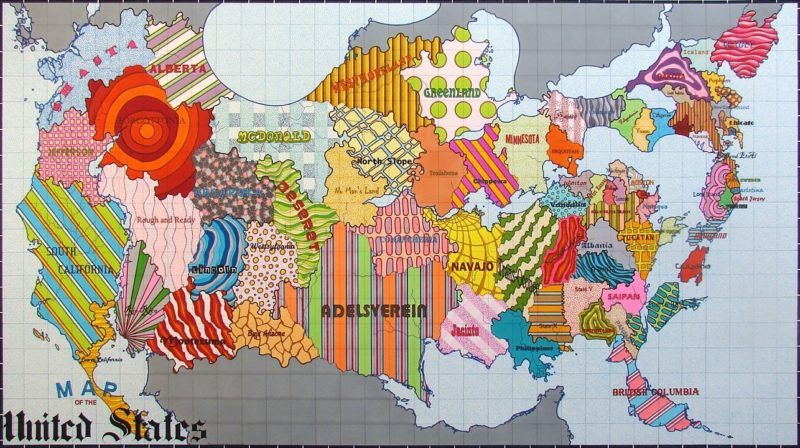

Lordy Rodriguez. “United States Map II (Not States),” 2010. Ink on paper; 40 × 70 in. © Lordy Rodriguez.

When I was growing up, one of my favorite books was the National Geographic Atlas of the World, stored with care in a large cardboard sleeve on my family’s bookshelf, near the Audubon’s Birds of America and some photo albums. This was in the early 1980s, when place names such as U.S.S.R., East Germany, and West Germany spoke of the Cold War era. I used this atlas as a kind of armchair travel guide, imagining all the places in the world I would eventually visit.

During graduate school, my fascination with maps grew as I learned about the maps of the medieval world (like the Herreford Mappa Mundi), which were based as much on faith as on geography or politics. Now, as an art teacher, I realize that the possibilities for mapmaking in the classroom are limitless. Maps can be ways to explore the world, to learn about other cultures and traditions, to get in touch with one’s ancestry, and to recognize them as byproducts of human civilization.

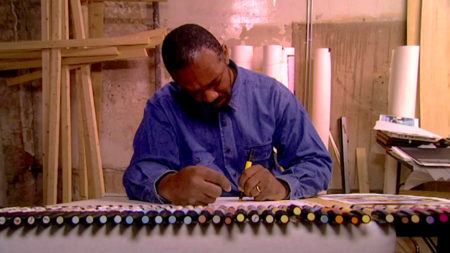

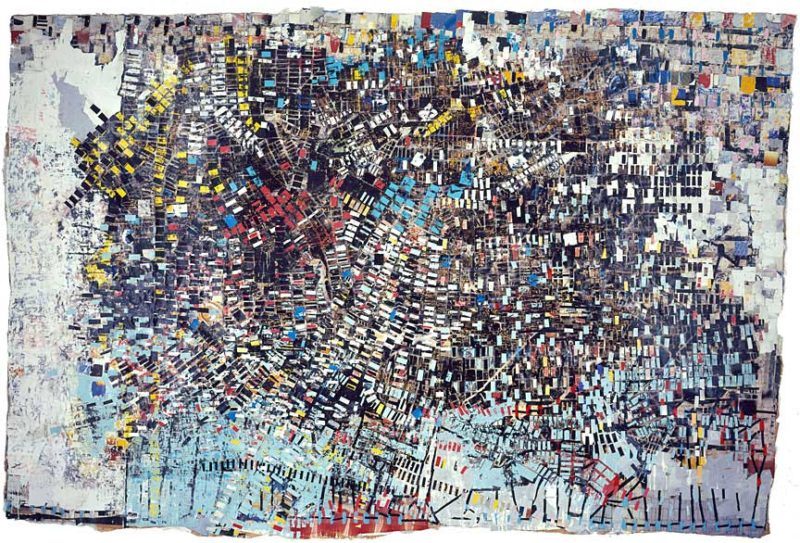

Contemporary artists use maps and mapping to explore all these ideas, but some artists stand out as perfect entryways to using maps in the classroom. In large-scale mixed-media works, Mark Bradford focuses on the geography of Los Angeles and uses the process and strategy of mapmaking as a starting point. He says, “I was really thinking of mapmaking and also the history of abstraction because in some ways I look at maps as these abstract grids.” He describes researching places with Google Maps, and he recreates the streets and buildings of specific neighborhoods using materials such as string or caulk, layering scavenged paper on top and cutting and peeling away layers to both conceal and expose the geography. The paper chosen for these pieces are signs and advertisements found in the neighborhoods that he depicts. For the work Black Venus (2005), Bradford used Google Maps to search for a particular address in a Los Angeles neighborhood known as an affluent Black community and invented a story about who lived there. Some of his other map paintings specifically refer to the L.A. neighborhoods shaken by the violence of the 1992 riots, which he personally experienced.

Mark Bradford. “Black Venus,”2005. Mixed media collage; 130 × 196 in. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Mark Bradford.

Bradford’s pieces are beautiful conversation starters with students and models for the process of research, reflection, and creation. When introducing a piece, I usually begin with a simple reflection routine, such as “I See, I Think, I Wonder,” to gather students’ observations about the work. Once they view Bradford’s segment in the “Paradox” episode, they realize his abstract work has deep personal meaning, and the places he chooses also represent moments in history. As Bradford says, the works refer to “the conditions that are going on at that particular moment at that particular location.”

I began developing a unit on mapping during the harshest part of the summer of 2020. My family couldn’t travel from our home, then in Saudi Arabia, to the United States, and we were locked in the land of sand. Each member of my family reacted to this confinement differently. All I wanted was to normalize the experience for our seven-year-old son. We talked about places he missed, and he would spend hours virtually traveling, with Google Maps as his guide. One location that repeatedly came up was Kimball’s Farm Ice Cream, a family-fun center in my hometown of Westford, Massachusetts. For my son, creating a map of this place alleviated some of his feelings of loss and gave him a much-needed activity. As an art teacher desperate for the return to a normal school year, I thought about how this activity could give meaning and perspective to other children and what different directions I could take with it. I had time to research, using resources such as Berry and McNeilly’s 2014 book, Map Art Lab, and a big stack of National Geographic insert maps, purchased from eBay.

Flynn mapping out Kimball’s Farm Ice Cream. Photo by Emily Relf.

By the end of the summer, we had relocated to the US, and for the first time in my professional life, I found myself teaching in a Massachusetts public high school, similar to the one I attended as a teenager, craving world travel. I had spent the past twelve years overseas, teaching expat or host-country communities, so this was a case of reverse culture shock. Launching a mapping project in art class was an experiment I’ve wanted to try for years, and now I had a brand-new laboratory. I asked myself: What places capture the students’ interests? Do they hold passports? What are their ancestries? What are their dream destinations? What are their worldviews? I was hoping they would answer me through their artistic intentions and choices for what to map out. The criterion for choosing a place was simple: it had to be a place one could locate with Google Maps, similar to Bradford’s process. Suggestions for making a selection included:

- A place you have always wanted to visit

- A place that is special to you in some way, such as a family holiday spot or your own home

- A place from your family’s past, such as the ancestral town of your grandparents or great-grandparents

- A place that holds some fascination for you but you aren’t sure why

With my seventh-grade class at Southwick Regional School, we explored artworks by Lordy Rodriguez and Yin Xiuzhen, noticing that artists can interpret places and play with geography. Rodriguez uses the rules of cartography while reimagining real places. The students responded strongly to Yin’s Portable Cities and were especially fascinated by her use of used clothes. I feel it is important for the students to see maps as a rich outlet for creative potential and to know there is no fixed interpretation of a place, even though maps can be deceiving and appear objective.

Yin Xiuzhen. “Portable City: Düsseldorf,” 2012. Suitcase, second-hand clothes, light, map, sound; 148 × 88 × 30 cm. Courtesy Pace Gallery. © Yin Xiuzhen.

We began our process with Internet research, and Google Maps gave us the bird’s-eye views we needed. We searched for images of our places of interest and crafted planning documents, with examples of animals, plants, buildings, food, and other cultural symbols for our places. This process was fascinating, specifically in the students’ choices of places; they became conversation starters and revealed a little bit about each of us. Parents’ or grandparents’ homelands were popular, specifically reflecting the strongly Polish community of this part of western Massachusetts. One girl selected Sentinel Island, off the coast of India, which she described as a place disconnected from the modern world. This sparked discussions about whether people are happier with modern technology and whether the island’s inhabitants have been affected by COVID-19. Maps of Puerto Rico brought forth a chat about current issues of statehood and citizenship (ironically, this topic came up on the same day we learned that Washington DC may become a state). Many students were drawn to Japan as a dream destination, which led to us discussing how aspects of visual culture, like anime, are so popular in the West (as well as sharing our favorite examples of anime). Cross-curricular connections came up as well: two students chose Alaska because their English Language Arts class was studying a book about the spirit bear. It seemed that a dozen possible topics arose just by going through the research process. From this research stage, the students used a variety of enlarging and drawing methods to draw out their maps, adding significant details such as landmarks, labels, and geographic features. From there, they could be as creative as they wished, using colors, designs, and patterns to fill in spaces, with any materials they had handy.

Art teachers around the world might agree that COVID-19 has imposed strict limitations on our usual creative processes. My students engaged in this project mostly during remote and hybrid learning, and some adaptations for accessibility had to be made. I had to assume my remote students had few art supplies, and I couldn’t give effective feedback during their art-making time on Zoom. My classes’ typical practice of encouraging experimentation, collaboration, and sharing materials has drastically changed as students are spaced apart, at home, beholden to Zoom, or have little access to supplies. While our mapmaking was limited to simple art materials such as markers and pencils, this restriction allowed the students to focus on line quality and detail. They looked closely at small details, such as the nuances in buildings, landmarks, and cultural patterns to fill empty spaces. The end results were exactly what maps should be: small images representing vast areas of land and water. I couldn’t help looking toward the future, imagining what other materials, techniques, and approaches we will use. I know these works and this project idea are just the beginning of a longer path, of using geography and cartography in the art classroom, for I believe that representing the ever-changing world we live in is one step toward understanding its complexities.