Interview

Portraiture, Performance, and Violence

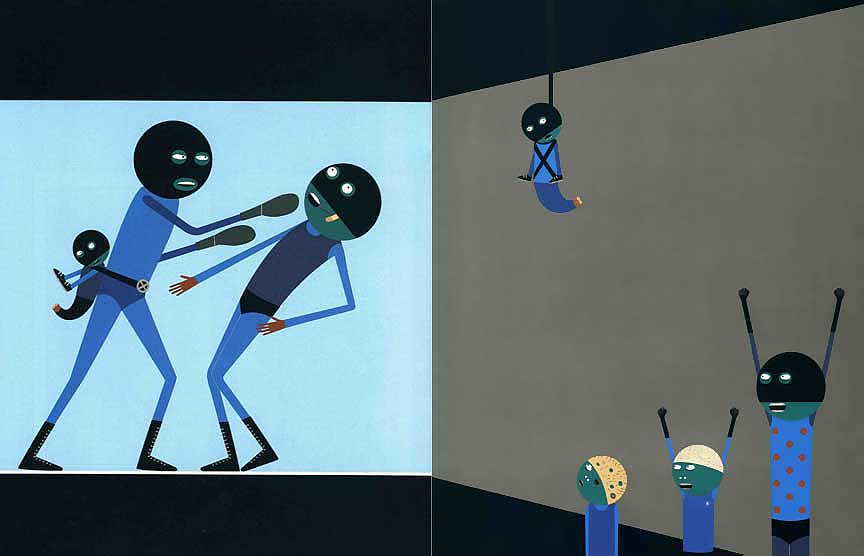

Laylah Ali. No title, 2002. Artist's book, digital production by Nicole Parente. Produced for the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Courtesy of the artist.

Artist Laylah Ali discusses her work’s relationship to portraiture and the role of performance, symmetry, and violence in her paintings.

Art21: Do you think that the term portrait accurately describes your work?

Ali: Just the ones that I’ve recently done of single figures. The way that they’re cropped is in reference to ubiquitous portraiture, formal portraiture. So, I call them portraits, but I mean a portrait that really isn’t of someone who exists; these don’t exist except in my mind. They certainly act like portraits and they want to be portraits, but at the end of the day, I don’t know if they are.

Art21: What characterizes a portrait?

Ali: I’m thinking about formal portraits, but the portraiture that I’m thinking of when I’m making these encompasses a much bigger range than I’m thinking about right now. I’m thinking of them as distinct individuals who exist or who have existed. The idea is for the distinctness of that individual to come through and to speak in some way about a narrative that is not readily apparent. So, something about the way the person is dressed or their setting or the weathering of their face tells you a story. The look in their eyes speaks of something larger. Think of society portraiture in the late 1800s, like a [John Singer] Sargent painting. He was commissioned to do portraits of very wealthy individuals. And you’re looking at the individual as much as you are at their dress, what they’re holding, what the setting is: the whole picture. With really amazing portraits, the painting of them also plays a role. The quality of paint and something about the eyes: those sorts of artistic decisions become an active part of really good portraits.

The idea of portraiture is a kind of storytelling, a distilled storytelling. I am interested in distilled narratives, so the idea of trying to tell a story or hint at something larger than the individual—through the individual—became interesting to me. It’s new for me to do this and I’m not sure where it’s going to go from here. I think this is the first step at looking at these individual characters and blowing them up large. I’ve had individual figures before in my work, but they have been more distant, more deep into the picture.

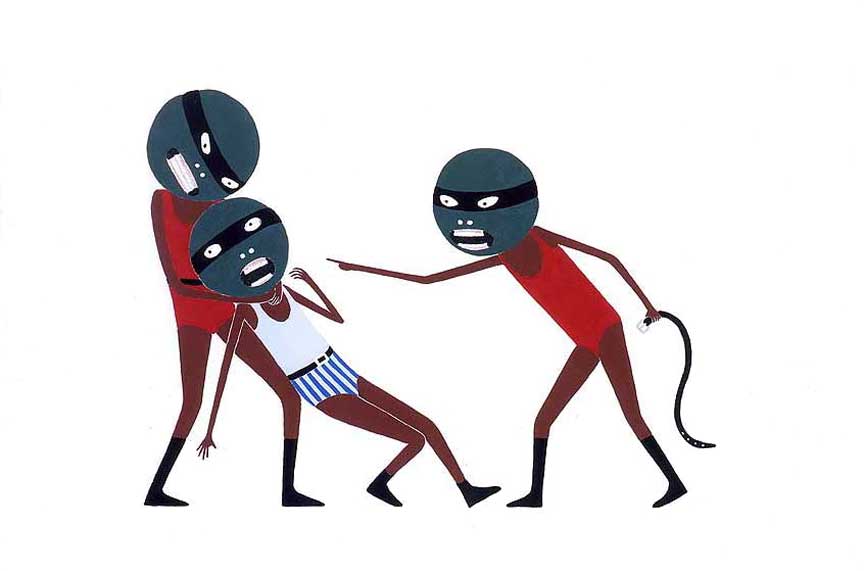

Laylah Ali. B Painting (Greenheads), 1996. Gouache on paper; 11 × 7 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Art21: What role does gender play in creating these individual characters?

Ali: I have no idea whether they’re male or female. I’ve almost eliminated that as a category, although they still get gendered because of what they wear. It’s interesting, because race still exists in the work. Recently it’s come to the forefront a little bit more.

Art21: Symmetry and violence both seem to play a major part in your work.

Ali: Well, [it’s] more than symmetry. I think of it as a kind of visual rhythm in the work. I feel like I have these rhythms that I work on, and I don’t know music [terms], so I’m going to make up my own: rhythms and sub-rhythms. The structural things have a kind of patterning or beat to them.

And the violence: I think when people say the word violence, oftentimes we think of the violent act. In my earlier work, it was more about the moment that somebody was getting strangled or hanged, whereas now there’s very little concentration on the moment when violence occurs. I’m more interested in what happens before and after. And the figure is the perpetrator of the violence, the victim, the negotiator. We understand or read violent acts through the characters and the figures.

Art21: Can you talk more about this idea of pre- and post-violence?

Ali: There’s always another violent act around the corner. So, pre-violence: when was that moment? Post-violence: the anticipation of the next act. The repetition is what I think is so striking. It’s not like one thing happens and you say, “Wow! That was just so terrible,” and it will never happen again. You know it will happen again, either where you’re caught up in a system, whether a family or war, or—if you’re in a situation as I happen to be in now—not involved in a violent cycle, witnessing violent situations erupt. I’m more in a witness position now. Not a direct witness, a kind of removed witness.

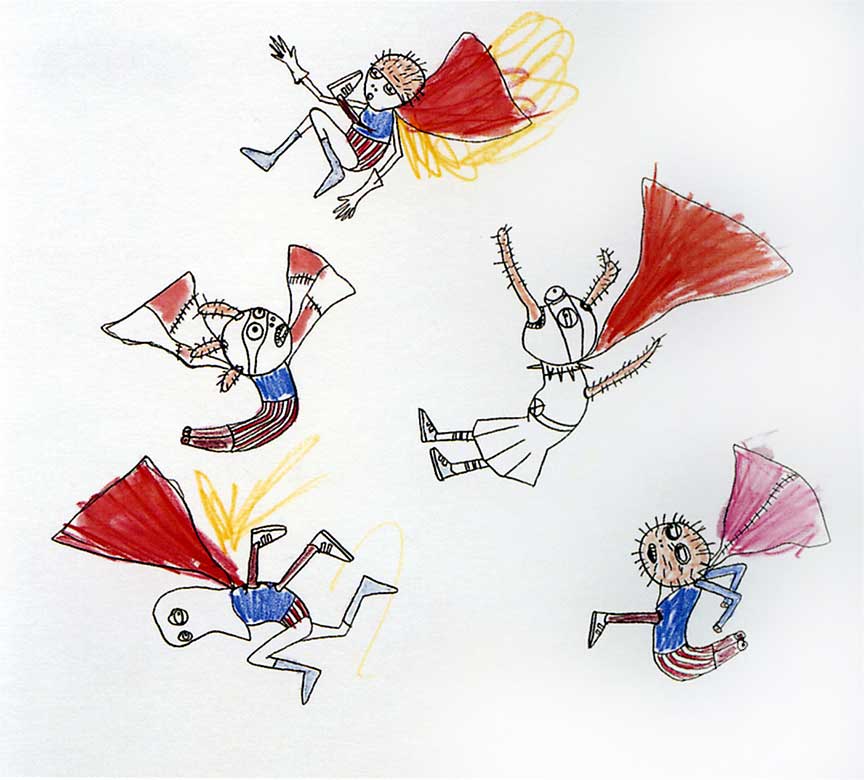

Laylah Ali. Untitled, 2002. Gouache, watercolor pencil & ink on paper; 10 1/4 × 11 1/2 inches. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Art21: What about your performance piece and the process of collaboration?

Ali: It’s really very different. I mean, it’s about as different as I can imagine something being, working with dancers and performance. Luckily, when I was in high school and college I was interested in theater for a while, so it’s not completely foreign. But it is foreign enough that when I walk in and there’s actual living, breathing bodies there with hearts beating, it’s a little freaky. It’s a little like, “Aaah! They’re all alive! How do you deal with alive people?”

Dean Moss [the choreographer] is trying to control and order the experience much in the way that I am trying to control and order my own work. But he has all of this other information and human will involved, which makes it extremely exciting and alive. Dean really is the person who works directly with the dancers; I’m not responsible for that part of it. And he’s been fabulous to work with. I think the most exciting thing—and the reason that I agreed to do it—was that it’s a little bit scary for me.

I met Dean, looked at his work, went to a performance of his, and felt like we were thinking about similar things in different ways. Not different at heart but different in approach. I didn’t think I could pass up the opportunity to enter into a kind of creative collaboration with somebody. Something like that doesn’t happen very often. I think in a really honest way, and I think Dean approaches it really honestly. It’s a real gift to be able to join in someone’s creative endeavor.

Oftentimes artists are brought into performances to make the backdrop, to provide the visual stimulation that’s two-dimensional. But that’s not what this collaboration is about; it’s more like, “Let’s put our minds together and see what this is about.” And that has been pretty amazing. I think that’s one of the risks artists should take every once in a while, to step outside of their creative process and see what happens when you leave the confines of your own way of doing things.

Art21: What about the word power?

Ali: Power? I don’t know how to think about the word power. It’s so overused. To empower: that’s supposed to be a good thing. People who have power: that’s a bad thing. So, power, to me, is too slippery. Control speaks to power, but it’s more about the mechanism, which I think interests me. So, I would say there’s a lot of contemplation about control. So much of the work is about me trying to control it. Yet it still defies me.