Interview

“The Music of Regret”

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Romance. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

Laurie Simmons discusses her 2006 film The Music of Regret, and how she came to use ventriloquist dummies in her earlier work.

ART21: Your film, The Music of Regret, has a romantic element to it.

SIMMONS: I’m surprised to think about the film in terms of being romantic because romance has never been an issue that I’ve grappled with or brought up consciously in my work, except in one series of pictures, [also titled] The Music of Regret, where the characters were two dummies, male and female. But maybe it was the influence of the things I love—music, musicals—which are absolutely unafraid to address that topic. I was thinking so much about the American Songbook and musicals and moving a narrative forward. Maybe that’s why romance finally came into my work. And at this time in my life, I’m ready to accept or own a kind of romance and melancholy or melodrama that I wasn’t ready to reveal before.

ART21: Does nostalgia play a role in the film?

SIMMONS: I’m so resistant to the idea of nostalgia. I know that it exists in my pictures and in the film, The Music of Regret, but I feel like I work against my tendency to go back in time. Nostalgia can be an easy shot, just an easy recreation of another time or another mood. I think there needs to be more there. And of course, nostalgia’s been used so much in film and fashion and art. And I’m just always thinking there must be another place to go, besides mining my own past, the look and feeling of my past, or everyone’s past.

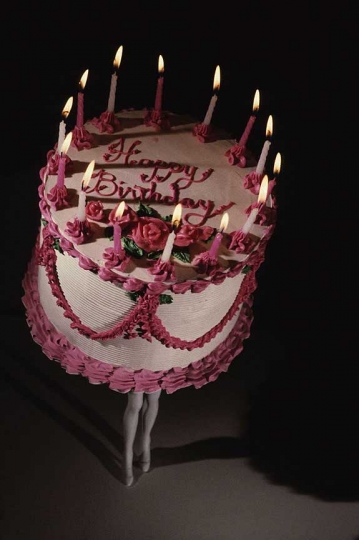

Laurie Simmons. Walking Cake II (Color), 1989. Cibachrome print; 64 × 46 inches. © Laurie Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

ART21: What is the relationship between the film and your photographs?

SIMMONS: In making the film, I did something that I’ve always wanted to do, which is, literally, to bring my work to life. I got a chance to really revisit my work—the characters and the ideas [in] just fleeting, still images or just a glimpse of a narrative—and figure out what would happen if, suddenly, I was looking at a photograph and the characters started to talk to me, or sing or dance. It’s a fantasy that I’ve had for a really long time, but I never really thought I would or could make a movie.

ART21: Did it make you push ideas further?

SIMMONS: Making a movie is such an incredible undertaking. There are so many things to think about. The initial image is one of my photographs. But everything’s moving, everything’s talking, everything’s in color over a period of time. So, I had to think about things in a way that I’d never thought about them before, with a kind of depth and breadth that was unimaginable to me before I actually did it. Fortunately, I had a lot of help. I’m really proud of the movie, because I did it, and I really love it. Meeting the challenge was really, really satisfying for me.

ART21: Making a film is so much more theatrical than making a picture. Was this a natural thing for you to do?

SIMMONS: My inner life about my own work is very theatrical and narrative. But that’s something I was always afraid to express because I came of age in a time when cool distance in the work and a more conceptual turn of mind were very important. So, I had a very secret inner life about the pictures that I was making. I had music in my head that was playing while I was shooting. Sometimes I had a narrative; sometimes I was thinking about a more specific situation. But I always wanted my still photographs to be cool and simple and to have an almost abstract edge. If the movie brings a kind of different reading to the work that I did twenty years ago, that’s okay; I’m ready to own that. But I was always a little shy about having that kind of information come out in the still photographs.

With the movie, I was ready to deal with everything that came out, even the idea that I would create a situation that could potentially cause someone to feel emotions or shed a tear. The idea of a movie and time-based work are completely wide-open in a way that the still photographs were not for me—because how much narrative could you pack into one image? And how interested was I in packing an image with narrative? I wasn’t. But a film? That’s a different story.

Laurie Simmons. The Music of Regret (Act III), film still, 2006. 35mm film; 40 minutes. Directed by Laurie Simmons; Music, Michael Rohatyn; Camera, Ed Lachman ASC; with Meryl Streep, Adam Guettel, and the Alvin Ailey II Dancers. © Laurie Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

ART21: Were you always interested in musical theater?

SIMMONS: I was always fascinated by musical theater, but it’s something that I had to be sort of secretive about. It’s the music that was playing in my home when I was growing up. My father had this big record collection that I took back to my room. And of course, I was listening to Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and old blues in high school. And I became really interested in jazz; I kept these records hidden underneath my Bob Dylan records. And I would bring them out—I was really obsessed with the lyrics, the melodies, the emotions that I felt.

But I had nobody to share that with, because I certainly wasn’t going to tell my father that I was interested in the same music he was. And my friends, if they did happen to catch me playing these songs, they were not amused. So, it was my guilty, secret pleasure. I’ve been studying this kind of music for so long, and I finally realized that I have more than a passing interest and knowledge in this kind of music and its history. So, when I did have the opportunity to make this movie, I thought, “I’m going for a musical.”

ART21: How did you start thinking of using ventriloquists in your work?

SIMMONS: I had a lot of old recordings of ventriloquists talking to their dummies—those kinds of narratives. I had songs by Shari Lewis, singing with Lamb Chop. Things that I remember from when I was a kid: Paul Winchell and Jerry Mahoney dialogues. So, I had all of those dialogues that I was listening to and working with.

ART21: There is a very particular type of humor in these dialogues.

SIMMONS: Humor goes in and out of style; it has its own fashion. Some of the jokes and dialogues—they’re very acerbic, very sarcastic. The jokes aren’t specifically funny. They’re very off. But I liked the way they were off because they’re off in the same way that I like my photographs to be slightly off.

ART21: How did the dummies in Act Two of the film originate?

SIMMONS: Those are dummies that I made for a series of works in the early ’90s. They came out of a time when I was tired of photographing dolls and female characters and wanted to introduce a male character. Of course, I didn’t want to use a real human male, because that’s not what I do. I tried to think of the way that men have been portrayed. Store mannequins didn’t interest me. And then I thought about ventriloquists and dummies—that relationship where they speak to each other like brothers or friends. They’re like foils. They’re like enemies.

And also I thought about how the dummy is such a metaphor for lying and telling the truth. The way the ventriloquist is able to say whatever he or she wants to say through this other character—that’s pretty amazing. You don’t have to take responsibility for anything that you’re saying, because the dummy said it or the dummy did it. And that reminded me of a lot of things, from newscasting to public speakers, to politicians, to friends. The whole relationship made me think about so many aspects of life.

Laurie Simmons. Clothes Make the Man, 1992. Installation view: Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles. © Laurie Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

ART21: Are the dummies a way to investigate certain cultural ideas?

SIMMONS: The interesting thing about the group of dummies that I made in the early ’90s is that they’re all identical. I think in total I made eight, and they’re absolutely identical except for different suits of clothing. And the series was called Clothes Make the Man. It was about these kinds of minute differences in the way we look or act that make us feel like we’re so profoundly different. Like, “I’m not like you because you’re wearing a blue shirt; I’m wearing a yellow shirt. You’re wearing a bow tie; I’m wearing a string tie. We are so different.” But really, these differences ultimately are not so great.

ART21: There is also a real person in the film. How did that come about?

SIMMONS: The original idea was to use the girl dummy, the wooden dummy, all the way through Act Two. As the music and lyrics became more complex, and the emotions became more complex, I wasn’t sure that a puppet could actually carry Act Two. That was when I decided that the puppet would become a real woman. I was nervous about it because the woman in Act Two was the only real person emoting or responding in the whole movie. Yes, there are dancers’ legs in Act Three, but they’re carrying around huge props; you never deal with their faces. So, that was a big consideration, to actually introduce a real woman into the mix. But I really felt it was important, and I’m glad that I did. I meant that I had to direct an actress, and that was new, but I did it.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Romance. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

ART21: Did the actress, Meryl Streep, become a surrogate for you?

SIMMONS: Well, initially, but after a while I stopped thinking about that. It would have been too uncomfortable to think about Meryl Streep portraying me in the movie. So, once she claimed the part, I stopped thinking about the part as representing me or my life. The first time I saw her, which was at a wig shop, it was very unsettling. I walked in, and Meryl had her back to me. And she stood up and turned around, and I saw her in the dark wig. And there was one moment where I thought, “This is very eerie; this is very odd.” And she looked absolutely beautiful in this long, dark wig.

Once she became the character, it wasn’t about me anymore. And in fact, right after that, I went back to the studio and had the dummy’s eyes painted blue; the dummy’s eyes had been brown like mine. And I stopped claiming that character as a surrogate self, as a version of me. That made it much easier to proceed, when I didn’t have to think about that character as being me.

ART21: Why does the theme of regret interest you? It seems to occur and reoccur throughout your work.

SIMMONS: Regret is the prevailing emotion in the film. It’s very much about the different guises of regret. That’s what keeps coming up. It’s something I’ve been exploring for a long time. Every way that I could think about it, I tried to make it come up in the movie. It interests me as a state of mind, as an emotion, as something that people become mired in. I think that, right now, the whole country’s in a state of regret. No matter what you think, no matter what you feel, you’re wondering if this was the right thing to do, no matter what side you’re on. Everybody seems like they’re wondering. On a small level, in their own lives, people are thinking about what might have been if they’d made a slightly different decision or about how one decision can cascade through the rest of your life and impact everything else that you do. So, yes, I’m really interested in regret.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2007 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.