Interview

Photography, Perfection, and Reality

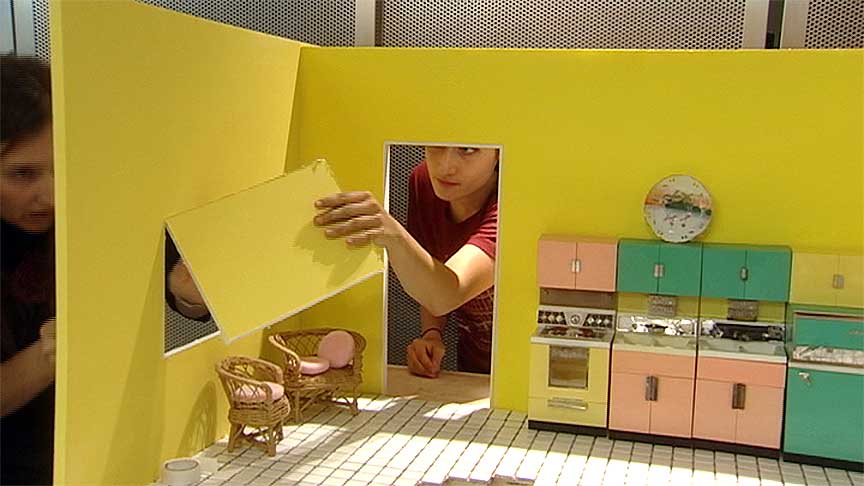

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Romance. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

In this interview, Laurie Simmons talks about how she got started in photography, and the roles that family, architecture, and symbolism play in her work.

ART21: How did you get started using photography?

SIMMONS: I came to photography a little bit late. I went to art school but did not study photography. I moved to New York and saw the way photography was being used—and I don’t mean photojournalism, I mean the way artists were using photography. I thought, “That’s it; that’s for me.” The whole notion of frozen time was completely new, and that’s what I was doing. I was making these setups in my studio where I was throwing things around and juxtaposing small pieces of furniture, walls, wallpaper, tops of books, just everything.

It was a crazy, chaotic mess and yet, in the end, I had a very still, quiet moment where I’d frozen time. And I expected viewers to believe that they were entering a real place that really existed, a place where time stood still. There was always a fascination with the artifice of the place that I was creating, which only existed for a couple of minutes, propped up by toothpicks and Scotch tape in my studio. And then in the end, I had this bit of frozen time and place.

ART21: There is something a bit Proustian about the sense of time.

SIMMONS: Oh, if I could only finish Proust, I would let you know, (LAUGHS) but that’s a project.

ART21: Your father was a photographer?

SIMMONS: Well, he was an amateur photographer. But I assumed everybody’s father was an amateur photographer in the late ’50s and ’60s. The goal of this era was to have everything be so picture-perfect. So, of course the next step was to preserve this kind of perfection into very organized albums of family photographs. Most of the people did that; my family certainly did. We were all given cameras and were expected to photograph.

Laurie Simmons. Untitled (Woman’s Head), 1976. Gelatin silver print; 5 1/4 × 8 inches. © Laurie Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

ART21: Do you think this idea of picture-perfectness is prevalent in your work?

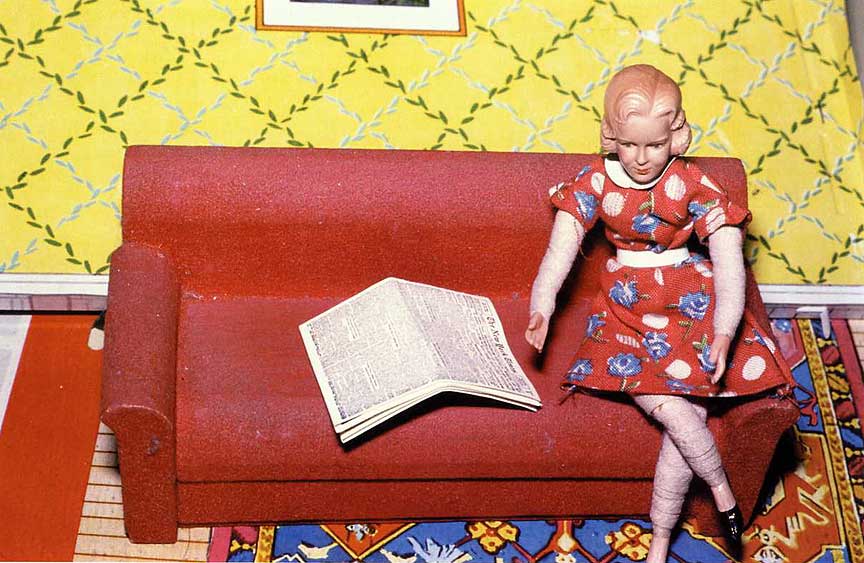

SIMMONS: I had a funny consciousness of the “Kodak moment” when I was a kid. I could see that when everybody was dressed up and ready to go out, or when the house was particularly clean, I had a way of framing things and separating myself from the situation—seeing it as something separate from me. And when I first started shooting the interiors, the first photographs that I ever made, I was conscious of creating a moment that wasn’t quite real, but was quite perfect. There was the real moment, when the house was a mess, and everyone was yelling, and the dog was running around, and things were out of control. And then there was another kind of reality that I preferred—pristine and still and quiet and beautiful and, lots of times, devoid of people—because life felt very chaotic to me.

So, when I made the first interiors that I call the dollhouse interiors (even though dolls didn’t appear in them for a long time), I wanted them to be picture-perfect, like those odd moments that I remembered from being a kid, when things were so beautiful. Of course, when you remember things, they get cleaner and more beautiful over the course of time. They just separate from their reality and almost have an aura. That’s what memory feels like.

I always want everything I do to be perfect (perfect-looking), given the inherent limitations of my work. How can I get puppets to look as real as possible? How can I get the background to look as real as possible? I’m never trying to make things look fake. I’m trying to work with what I have.

In the movie, The Music of Regret—for Act Two, I wanted the snow and rain to feel so real. Of course, there were big plastic snowflakes getting in Meryl Streep’s eyes and making it difficult to work, but in the end it all worked. The only rain machine that we could get a hold of—I don’t think was the most up-to-date. It was kind of like turning a shower on. But we made it work. And that’s how it’s always been with my pictures. I use what I can and try to make it as perfect as I can, but I’m not starting with a setup that’s perfection. I’m not Hollywood. (LAUGHS)

Laurie Simmons. The Boxes (Ardis Vinklers) Ballroom II, 2005. Flex print; 40 1/2 × 84 inches. © Laurie Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

ART21: What kind of research do you for your pictures?

SIMMONS: I think that artists are always doing research on their own behalf and for their work. For some artists, it’s reading. For some, it’s shopping. For some, it’s traveling. And I think that there’s always this kind of seeking quality that artists have where they’re looking for things that will jog them and move them in one direction or another. For me, movies and books have always been research. Finding objects will always stimulate a series or get my mind going in another direction. I might be wandering around and see a figure or a piece of furniture or a picture that just starts me thinking about a whole other direction that I can move in. And of course that has to intersect with what I’m thinking about, my state of mind, my feeling about current politics, or some psychological issue that’s pressing. I see that all as research—just having all the threads of your life come together to tell you where you should go with your work.

ART21: Are you interested in the idea of family?

SIMMONS: I’ve always been more interested in the idea of domestic space than the idea of family specifically. I’ve never really tackled the idea of representing family in my work because I don’t really know how to do it. And I’ve always resisted a psychologically descriptive place in my still photographs.

I love the look of domestic space, both historically and in the present. I love the look of the figure in domestic space. So, that’s been my subject. I always say I’m like a dog with a bone—that was my subject with my first photographs in the late ’70s, and it’s still my subject, in a number of ways. Even the images in the film reflect that interest.

ART21: What influenced your use of photography, early on?

SIMMONS: The most important thing to me when I started to shoot my first photographs in the late 1970s was that I was an artist, not a photographer, using photography as a tool. First of all, I hadn’t studied photography, so I was terribly self-conscious about my skills (of which I had none). I taught myself and also had my friend Jimmy DeSana pretty much teach me everything.

I was really interested in work that I saw in New York, work that used photography in a completely unique way, in the more ephemeral works of art—things that could disappear, that only existed for a minute and needed to be documented with a camera. You didn’t have to be super-skilled in order to pick up a camera and use it as a tool in your work. That was so completely liberating for me to think about. And I was so excited that I could make things, shoot them, send the pictures to the drugstore, not have to have a darkroom, and not have to be bogged down in photographic history—which, by the way, was only a hundred years old.

So, it was really amazing to realize that I could use a camera, and also that I had this funny kind of quasi camera-history, shooting snapshots and having everyone in my family have their little Kodak Brownie cameras. In a way, it was like doing something that I was totally used to, that was familiar to me.

But also, I was starting to explore completely new territory. And I knew that I had a lot to learn. I thought, “If I’m going to pick up this camera, even though I won’t call myself specifically a photographer, I’m going to learn the history. I’m going to read every book I can. I’m going to go to the Museum of Modern Art and look at their collection. I’m going to go to galleries and ask them to pull out works for me to see.” I did that so that I could be conversant in the history and then start to play around with the camera in a way that was, maybe, a little bit less expected.

Laurie Simmons. Woman/ Red Couch/ Newspaper, 1978. Cibachrome print, 3 1/2 × 5 inches. © Laurie Simmons. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

ART21: Now, looking back at your photographs, do you see art historical influences you didn’t notice before?

SIMMONS: I realize how much more I’ve been influenced by older painting than I let on. There’s a formal compression of space, a juxtaposition of color—things that were in my mind that I never really accepted as influences, ways that I wanted my photographs to look—that I never really understood came so much from Matisse or Manet or even Picasso. These are things that sort of insidiously worked their way into my mind when I was taken to museums as a child, when I was very itchy and not quite understanding if I wanted to be there or not. These things came out later in my pictures. But, you know, there’s also Life magazine in there, and old TV commercials, and fashion photography. It ends up being such a mix of influences that come to bear.

ART21: What about still life?

SIMMONS: I would never say that there’s a connection between my work and the history of still life, even though what I do in my studio is to set up one still life after another. And life truly is still in my studio because I’m using dolls, mannequins, and puppets and nobody speaks. And once a setup is made, it’s there until it falls over, which is pretty frequently.

ART21: What about architecture?

SIMMONS: Architecture in the landscape is something I’m extremely responsive to and constantly trying to recreate in some way in my work. Certainly the tourism series that I did in 1984 really addressed architectural monuments and aspects of visiting places and the monumentality of buildings or wonders of the world. In my studio, I’m constantly trying to recreate images or moods that smack of a kind of architectural importance. It’s not always easy to do on a small scale, but it’s something that I aspire to and something I’m very responsive to.

ART21: And houses, in particular, find their way into a lot of your work.

SIMMONS: Houses have always been very symbolic to me. Of course, when I had the opportunity to design a toy, I made a dollhouse—a modernist dollhouse. I thought, “Well, that’s missing in terms of kids’ toys.” I really made that dollhouse because I needed another prop to shoot. And I had a great time. The Plexiglas colored doors slide over each other, and they become different colors. It’s a very chameleon-like dollhouse. So, for me, it was the perfect prop. I did spend a long time shooting it. But architecture is something that I’m pretty awed by. The power of being able to build a large structure and stand in front of that structure—in a sense, it’s what I try to do in my photographs. I make something that’s so small; I shoot it and give it a kind of presence. Sometimes I blow the picture up as big as eight feet tall, and I give this very small thing this enormous second life.