Interview

Culture and Aesthetic Sensibility

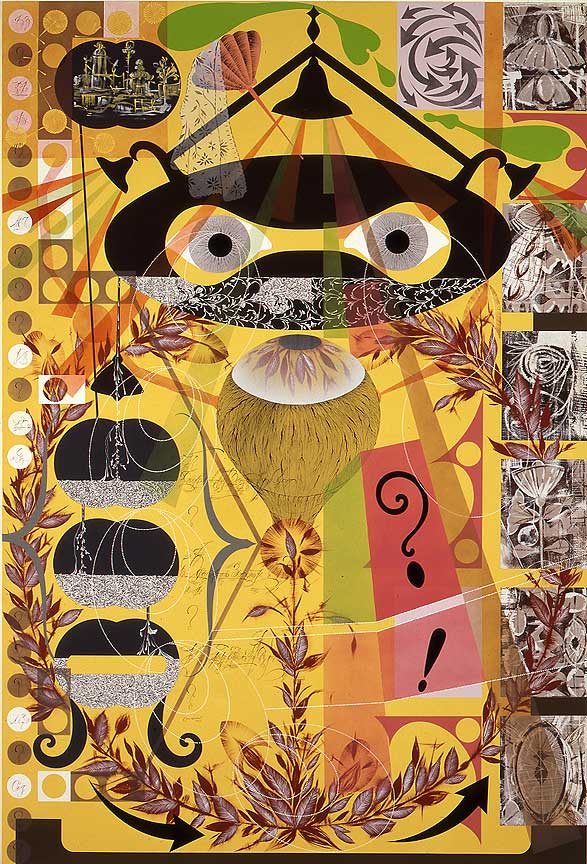

Lari Pittman. Palace, 2006. Cel vinyl and aerosol enamel on gessoed canvas over panel; 102 x 86 inches. Private collection. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Artist Lari Pittman talks about his relationship to his hometown, Los Angeles, as well as the ways in which time and balance are investigated through his paintings.

ART21: Do you often think about who your audience is?

PITTMAN: I like that the work is visually very declarative and available to everybody. I think that multiple viewers can approach it very differently. For example, I’m always excited when the UPS man or the water man comes in to the studio to make a delivery, and they immediately respond to the work—give a thumbs-up, that type of thing. I’m really taken by that, that the work is available on a very quotidian level. That makes me happy.

But I’m also interested in the work occupying a denser critical territory that would require a different type of visual literacy. I’m thrilled that the work is not confined to one demographic, that it is actually astoundingly mobile, in that sense. I think that’s a political resonance of the work. It just doesn’t occupy the confines of a type of writing that might occur in Artforum or in October. And I think it has to do with the visual generosity of it. A lot of work can only occupy very specific linguistic territories or very specific critical territories. But I think that my work has the capacity to navigate between the very distant poles of populist and elitist.

ART21: Where do you fall on those two poles?

PITTMAN: I’m grateful and thankful for having a charmed life and a certain amount of privilege. Within that framework, of living somewhat inside a bubble, I think what keeps me radicalized is being aware of the overwhelming hatred that is exhibited by the American population through legislation passed against homosexuals. So, I can lead quite a pretty life, but it’s always brought down by very aggressive strains in American culture that, in a way, puts me in my place.

ART21: How does living in Los Angeles influence your work?

PITTMAN: I think, as chaotic as American culture is—sadly, ironically, or even perversely—I thrive on that. I’m able to carve out a tremendous amount of freedom, particularly in Los Angeles. I don’t think I would be capable of carving that out in, let’s say, Europe or Latin America. I don’t think I could do it.

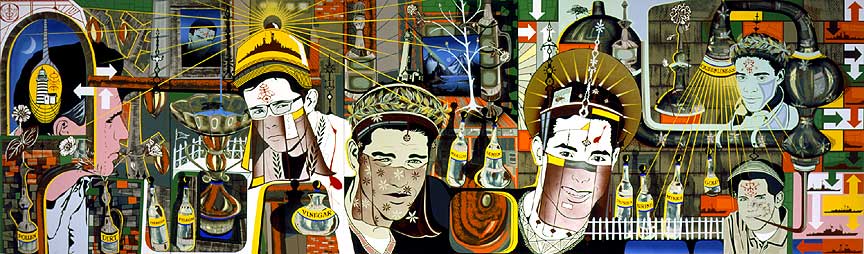

Lari Pittman. Untitled #8 (The Dining Room), 2005. Cel vinyl, acrylic, and alkyd on gessoed canvas over panel; 86 × 102 inches. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York.

ART21: Do you identify yourself equally as an American and a Latino?

PITTMAN: If there’s a stronger side to my dual identity as both American and Latino, I think there is a very strong Mediterranean core to who I am. I need a lot of sun. I can’t live under a cloud cover that doesn’t allow for a big open sky. It really comes down to something as climactic as that: I need to have a lot of light. I get depressed there isn’t, so I need a lot of sun.

ART21: Where did you grow up?

PITTMAN: I was born in Glendale, California, which is the community next to Los Angeles. Ironically, my studio’s now on the border of L.A. and Glendale, and it’s where I have my car washed. I always remember my mother saying, “You were born on the fifth floor.” So, from the carwash, I see Glendale Memorial Hospital, and it’s a really great feeling. So, I look up at the window, and I think of my mother, who is gone now.

But, growing up, my formative years were spent in Colombia. My mother is Colombian, of South American and Italian ancestry. My mother’s family was not [one of] practicing Catholics; they were social Catholics. My father is Southern, from the United States. He’s from a Protestant background, though he was an atheist. I grew up in a very hybrid world.

ART21: Can you say a little about the sense of time in your paintings?

PITTMAN: The paintings show the viewer many temporalities. There’s climate, and there’s time. Sometimes there’s even an indication in some of the paintings that the top half of the painting might be at night and the bottom half in daylight. I think that, in southern California, whose only history has been hyper-capitalism, hyper-capitalism foregrounds this idea of episodic time: “This is the eight hours for work, this is the eight hours to sleep, and this is the eight hours for waking leisure.” Capitalism really enforces compartmentalized, sequential time. As I look back on my formative years, I didn’t grow up in that sense of time. You have to take this in a broader sense. Latino time is profoundly bittersweet because of its simultaneity. Even oppositional events can occupy the same spatial moment, the same time moment, and not really be contradictory. They’re just there, side by side. And I think that simultaneity of time and imagery exists in the paintings.

ART21: You manage to strike a funny balance between gore and beauty in your work.

PITTMAN: If you have a bittersweet cultural context, it allows you to entertain the possibility of the gorgeousness of personal suffering. You can actually fetishize it and make it beautiful. Suffering and beauty are not antithetical but actually complementary. It isn’t about morbidity. It’s actually a cultural mindset that is predisposed to aestheticizing even pain and suffering. It’s not seen as decadent. It’s just about a duality of things.

Lari Pittman. The sounds of belief, to an atheist, are very touching, 1988. Acrylic on mahogany panel; 96 × 64 inches. Private collection, Los Angeles. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

ART21: When did you start using silhouettes in the paintings?

PITTMAN: I started to use silhouettes in a body of work in the late 1980s. The use of the silhouettes in those very early paintings was not about discussing something specific or about autobiography or personal experience. They were simply being used as surrogates to discuss social conventions, human behavior, encoded behavior. The idea of code is always really important in the work, and surrogates can help you advance this idea. So although, visually, the work appears to have a very strong declarative voice, what is actually being advanced in the paintings is a subtext or a code. When you’re looking at the work, you’re looking at something visually declarative, but it requires a sub-textual reading or a capacity or predisposition for reading code. That’s why I used the Victorian silhouettes. It was just a great conceptual armature to be able to filter social code through.

ART21: Which artists interest you?

PITTMAN: I’m interested in artists who have a subtext or a code. For example, Balthus is a very unsettling and perverse painter of great beauty. Sometimes his work can look quite banal, but there’s a code there—and in some people’s perception, a disturbing kind of code. I like the possibility of something looking one way but meaning another. Picabia’s late paintings—the almost soft-porn paintings that he did at the end of his life—those have a code. I’m not sure completely what the code is, or how to crack the code, but I like the evidence of it.

A lot of Western European religious painting is filled with code. We’ve come to understand that these religious paintings are a ruse for a discussion of sexuality or social commentary. I like the idea of the ruse, the pretext, the code, the subtext. It’s a bit high hat, but I like that. I like that the work is very visually available and declarative to everybody. But watch out: there’s a code, and you better know it. So, in that sense, the work is a little pissy.

ART21: Your newer paintings seem to point more inward than outward.

PITTMAN: The last two bodies of work and the body I’m working on now really do address more directly the construction of a personal life and what that entails—what actually occupies it and what, literally, it looks like. That’s what precipitated the titling of the last paintings, in terms of rooms of the house: The Dining Room, The Living Room, In the Garden. The titles of these paintings indicate, on a political level, the importance of residential space that is different from public space, in terms of aesthetics and safety. For me, public space is intrinsically male and heterosexual. And residential space, which is the armature that I chose to make the paintings about and through, is a more polymorphous space that allows, historically, for more polymorphous identity. That’s why residential space becomes amplified, for me, with ideological resonance and then worthy of some sort of representation and depiction in the paintings. So, it was important to make a painting about a dining room, a living room, the garden, and infuse that with as much power as the banking world or law.

Lari Pittman. Thankfully, I will have had learned to break glass with sound, 1999. Acrylic, alkyd, and aerosol on mahogany panel; 96 × 64 inches. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

ART21: Are you interested in the tradition of memento mori?

PITTMAN: Memento mori is a big part of the work. I’ve actually literally made memento mori—one of my forays into small tabletop sculptures. In the mid-’80s, I did these painted gourds. Memento mori is bittersweet because you want to commemorate death, but you are consumed with the mandate of aesthetics. One mandate is to address life and death, and the other mandate is about aesthetics and connoisseurship. They must be fused together in the object.

ART21: Aesthetics also plays a large part in the rest of your life.

PITTMAN: I’ve never lived a stripped-down life. I don’t think I could. So, regardless of fortune or misfortune, I would devise some sort of bubble or protection for myself. I mean, in that sense, it’s a really keen sense of survival and a voracious one, really. So, regardless of what situation I find myself in, I think that I would use aesthetics as a weapon for self-protection. The embellished Lari, the embellished work, is the real work.

ART21: There is a brutal side to the work, too.

PITTMAN: I know that the work has a brutal side to it, and there’s even a strong implied violence to it, an internalized violence. Not a personal one—a social violence. And I want it to not just be a document of will alone, or power alone. Somehow it has to be mediated through its appearance. I invest a lot in the power of something looking one way but implying another. I’m interested in the brute force of high tea. Maybe that’s what I identify with.