Interview

Craft and Influences

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, Romance. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

Lari Pittman discusses his earliest teachers and influences, as well as the role craft plays in his work.

ART21: Do you strive for perfection with your paintings?

PITTMAN: For me, craft has always been an ideological component in the work because it’s about a type of focus and social comportment that usually isn’t expected of a male. There’s a dutifulness that historically has been referenced or attributed to females, so I’ve always seen my devotion to craft as a type of protest.

ART21: How is an interest in craft a form of protest?

PITTMAN: In the applied arts, that attention to detail in craft by males is more permissible. But this kind of fussiness, lavishing this type of almost picky detail on a very big painting, just isn’t always attributed to what men do. For me, from very early on, that attention to really fine craft was a way of temporarily transgendering. I like that feeling. I don’t know if I can explain that, but maybe it’s an enculturated transgendering—not some sort of essentialist idea of gender.

ART21: Craft is also about pride in one’s work.

PITTMAN: I don’t know if it’s about love of the object, but I’m very prideful. I think that craft is a conduit for that. I like that craft also gives a vanity to the object. And that is imparted to the viewer. The object is very aware of its own vanity, as I think I am, too.

ART21: Is there a difference between being a craftsman and being an artist?

PITTMAN: I’m very attentive to the fact that I’m willing to temporarily be just a facilitator when I’m making something. That’s actually a part of making paintings that I enjoy very much. I’m not as invested in authorship. There’s a large part of the making in which I have no sense of being an artist—it’s just craft and direct application. And at the end of the day I have to step back and say, “Okay, what does this all add up to? Will all these activities and actions conspire to actually create content?” That’s the hope at the end of each day.

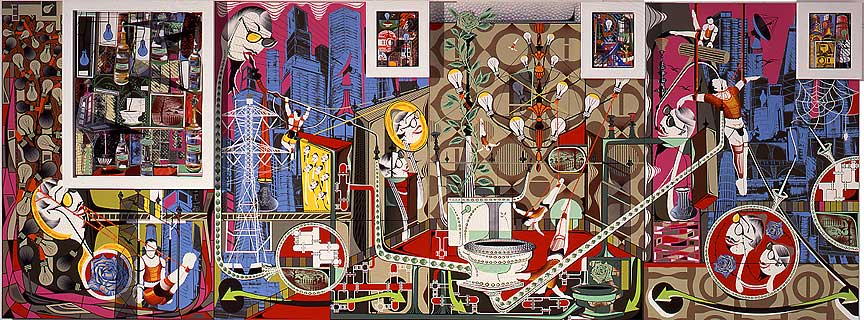

Lari Pittman. Once A Noun, Now A Verb #1, 1997. Flat oil on mahogany panels with attached framed work on paper and three attached framed works on panel; 95 × 256 inches. Collection of Norton Family Foundation. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio.

Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

ART21: Who influenced your work, back when you were an art student?

PITTMAN: One of the things that was valuable to me at Cal Arts was looking at histories that had fallen between the cracks. We looked at artists that I still love to this day, the female Surrealists: Remedios Varo, Leonor Fini, Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo. Also, Florine Stettheimer and Suzanne Duchamp. It was great to understand that Marcel Duchamp was very devoted to Stettheimer and really loved her work. It was a particular lens, looking at female artists, but it revealed a different approach that was neither part of the canon of The Museum of Modern Art or the canon of art critic Clement Greenberg.

I really come solidly out of a revisionist moment. Painting was moribund at the time and needed fixing up. It dovetailed into a really serendipitous moment, for me. It was this structure of thinking that was seen as exhausted. And I was a young artist going through exercises of historical revisionism and saying, “Oh, maybe I could see my face there.”

ART21: Do you feel like an outsider, in the way these women artists were?

PITTMAN: I’ve never felt like outsider, but I understand Otherness. Maybe it’s the way that my parents loved me; I always felt complete centrality. I always have. But that doesn’t mean that the world’s going to accord me that. (LAUGHS)

ART21: Who were some of your teachers?

PITTMAN: Elizabeth Murray and Vija Celmins—the professors that I had at Cal Arts—they were both very hard on me, but very encouraging. That was part of the coming of age, that and seeing, adoring, and envying a certain type of reductiveness. I love minimalism, but I realize I can neither physically do it nor see my own face in it. I look at minimalism as Other. I am capable of Othering it. (LAUGHS)

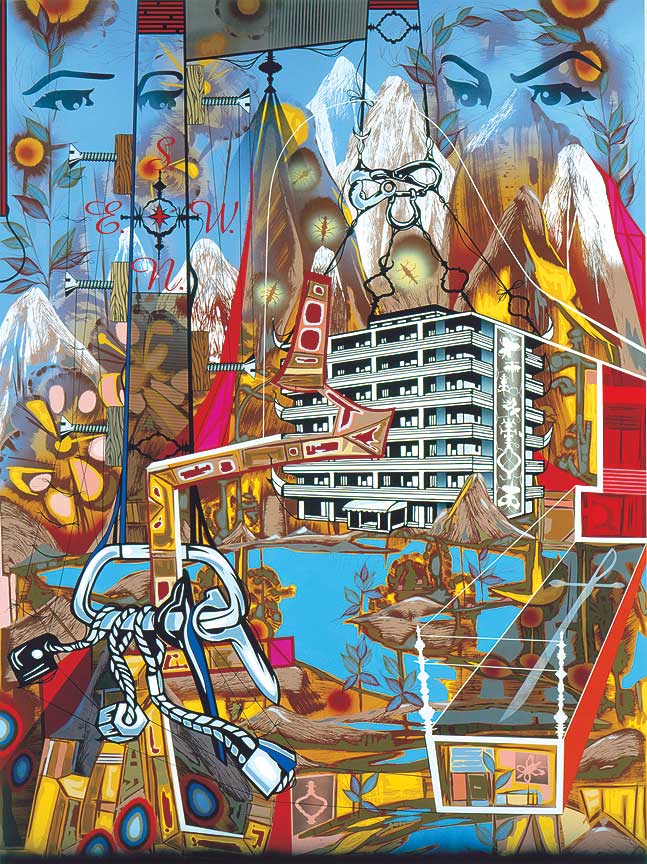

Lari Pittman. Untitled, 2002. Flat alkyd and spray paint on gessoed panel, 102 × 76 inches. Collection of Barbara Gladstone, New York. Photo by Douglas M. Parker Studio. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

ART21: Is there a kind of Orientalism in your paintings?

PITTMAN: What you’re talking about is a type of obtuse and almost incorrect Orientalism in the work. I think that is a part of it, and I completely understand the problematics of that discussion. I guess where I find some sort of permission to indulge in a type of Orientalism is deep within the codes of mid-century sexuality. Orientalism was actually a code for homosexuality, historically. This idea of Orientalism—it’s a very broad term for me, a colonialist term. I see it as an obtuse, highly encoded vehicle for the discussion of identity, which is useful to me. All through the paintings, there are hints of exoticism; the aesthetics are aestheticized. I think that that’s part of the world you escape to or want to go to. Maybe Orientalism isn’t the most accurate way of describing it, but for me, it’s still useful to use that word. It’s a very decadent idea; I understand that.

ART21: But it doesn’t have to be decadent, does it?

PITTMAN: It’s a completely fabricated, highly mannerist moment. Either you go with it, or you resent it. The experience of standing in front of the painting is not a simulation of anything, but it is a highly artificial moment of representation. And the paintings have always been relentless about that. You have the same type of negotiation as a contemporary viewer going to see opera; there has to be a complete understanding and acceptance of the whole mannerist endeavor, or else you’re just not going to enjoy it. All the paintings set up this intense mannerism. Everything is hyperbolized and highly decorated. Even the decoration is decorated. It’s trying to insist on the possibility of a primary experience, but within the confines of something very artificial. The work doesn’t shy away from that.

ART21: On the surface, your work appears very chaotic. But are you always working from an underlying structure, at the outset?

PITTMAN: I know the work looks visually micromanaged, and maybe it is. In the chaos of what I’m showing you, there is actually a rationalism of structure underlying everything. But a big part of the making of the painting is me thinking on my feet and making decisions on the spot about how to bring this representation to some fruition. I don’t always know the outcome.

I’ve come to understand and internalize the spectator’s appraisal of the work. One of the things that I’m ambivalent about, but don’t totally discard, is the fact that the work might seem a lot more constructed and pre-planned than it actually is.

ART21: What is the process of making paintings like, for you?

PITTMAN: I don’t necessarily view the making of the painting as a sequence of solving problems. I see it more as a sequence of responses. So, for me, there’s the big gesture: “Okay, I did it. Now what am I going to do with it?” I don’t necessarily see it as a problem, but more as a challenge. How do I enhance the meaning? How do I perfume it? So, it’s more of a call and response. I’m always allergic to problem solving because I just think it’s so Puritan.