Interview

“Hiroshima Projection”

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

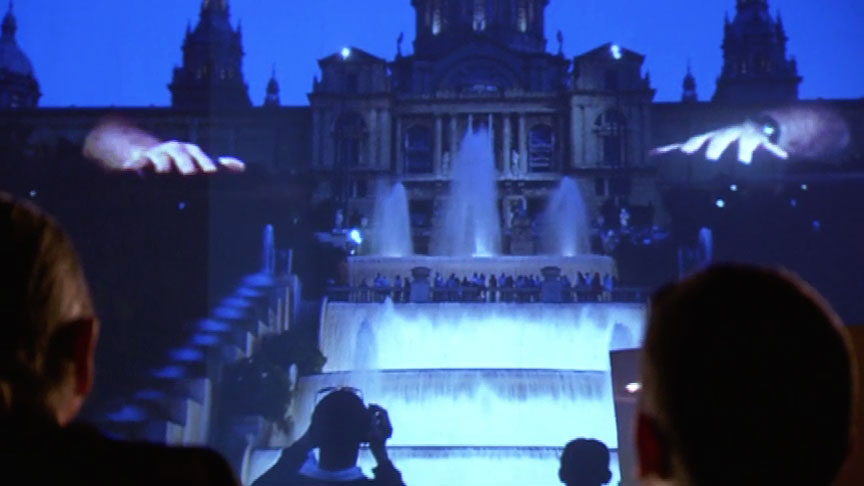

Krzysztof Wodiczko discusses his 1999 project, Hiroshima Projection, which involved projecting the hands of atomic bomb survivors onto the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, one of the few structures still standing after the blast.

ART21: Why did you decide to do a project in Hiroshima?

WODICZKO: I received the Hiroshima Art Prize. According to what is written in a text describing the prize, it’s given to those who contribute to world peace as artists. I don’t think it’s really possible to say that someone like myself contributed to world peace. I don’t think I deserve this prize, but once it was given to me, I decided to accept it on the condition that I will try to deserve this prize. I will be spending the rest of my life trying to deserve it. This gave me additional motivation to keep developing more public projects. It was also a possibility to do a large public project in Hiroshima. I proposed a projection, which was to take place the night of the anniversary of the bombing—which was a very important event worldwide, in Japan, and of course, most importantly, in Hiroshima.

The issue is perhaps more philosophical: how can we work towards peace? Maybe it’s not right to discuss here, but I have to say something for the record about peace. My position is that you cannot work towards peace, being peaceful. If the peace is to be one where everybody’s quiet and doesn’t open up—share what’s unspeakable, offer unsolicited criticism, defend others’ rights to speak and encourage discourse—that peace is worth nothing. It reminds me of the kind of peace that was secured in my old country under the Communist regime. That is the death of democracy. That might have consequences as bad as war—bloody war and conflict. So, to prevent the world from bloody conflict, we must sustain a certain kind of adversarial life in which we are struggling with our problems in public.

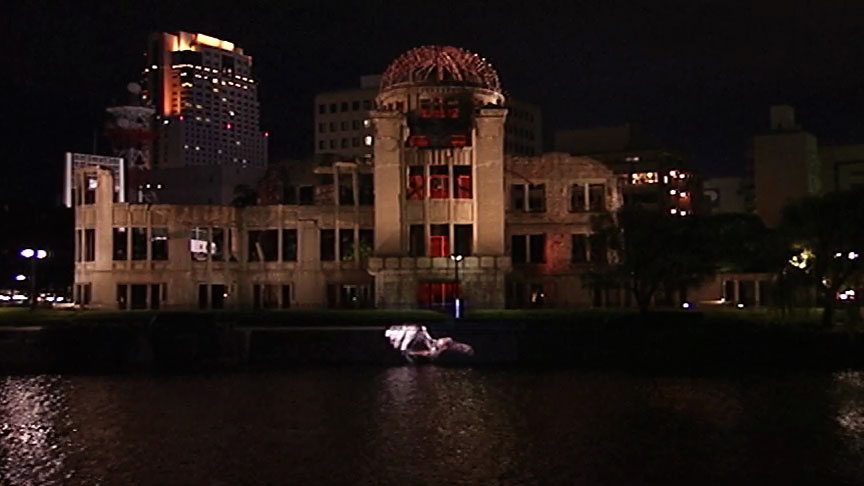

I started working on my Hiroshima projection with the assumption that we were going to re-actualize the A-Bomb Dome monument (one of the few structures that survived the bombing—just underneath the hypocenter of the explosion) and reanimate it with the voices and gestures of present-day Hiroshima inhabitants from various generations, starting with those who survived the bombing, who witnessed it; their children, who may still remember; their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. So, all those generations somehow connect through this projection—not necessarily in agreement, in terms of the way the bombing is important and the way the meaning of that bombing connects with their present experiences. The fallout of the bombing is physical and cultural, psychological.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

I started to talk to survivors of the bombing, not only the Japanese but also those who were treated as non-Japanese, so-called Koreans. Here, we’re talking about slave laborers who were bombed together with their masters in Hiroshima—for whom, at the time of this project, there was no room in Peace Memorial Park. Their monument was outside; now, it’s moved inside. But their voices were never heard as equal; they were sort of third- or second-rate victims. Now, they could speak through this projection freely and actually bring various personal experiences and critical thoughts about the way they were treated by the authorities in Japan.

We have very young people: for example, the person who was in love with a young man, and they were planning to get married, and the parents of this man opposed the marriage on the basis that she was born in Hiroshima. According to their misguided imagination, she was carrying some genetic disorder that will be a danger for the family in the future. The same person was questioning her own reaction to certain events in Japan that were carrying traces of chauvinism and racism. Another person was talking about conversations overheard in her father’s office, about good times—that is, during the last war, where companies (Mitsubishi, for example) had great military commissions, producing armament in Hiroshima and enjoying economic prosperity. Those fragments were transmitted through this monument, by gestures and voices of participants of various generations.

One person was the granddaughter of this imperial army officer, speaking about the way the atmosphere at home—as she called it, “boot camp”—affected her personality and traumatized her, and also how much school colleagues were responding to her, adding to this as if it was another war. So, she was caught between two continuations of World War II—a domestic environment and school—which seemed to be an unfortunate experience of many young people in Japan.

Connecting various generations of people is the case with many of my projects. There is something happening among participants—that they form certain links, hear each other, join each other, share. There’s what’s happening between them and their families. In the case of the person who told the truth for the first time about this situation at home, she had to speak to her family among those five thousand people standing across the river. It’s easier to be honest speaking to thousands of people through a monument than to tell the truth at home to the closest person. The question is: what will happen after such a statement? The report that I received from her is that the situation is better; she said, “Before we were silent. Now we argue about it, and that’s peace.”

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: What are your three citizenships?

WODICZKO: Polish, Canadian, and American. Perhaps it should be off-the-record (LAUGHS) for my own safety, in the present environment of conservative patriotic spirit. I have also French permanent residence.

ART21: Can you say more about your own personal connection to World War II?

WODICZKO: The fact that I was born during World War II, and my childhood was on the ruins of war (both physical and political, and perhaps moral, and definitely psychological) is probably a sign that I am qualified to understand at least a little bit of what survivors have gone through—my mother being a Jew who survived the war, whose entire family was killed during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and who gave birth to me in the midst of all this.

When I first met the people of Korean origin who lived in Hiroshima and survived the bombing, the way they were speaking sounded like my mother. The most similar aspect was the sense of humor: the type of humor of a survivor, using humor to cope with the worst. It’s enough to be Polish, to have that sense of humor, but being a Polish Jew gives you double qualification to offer this kind of response, like I heard from the Koreans. That was very helpful because they recognized in my face that familiarity, and it helped to develop trust. Without trust, there is no possibility for my work to develop. Trust is the starting point. The people who are participants—who become co-artists—must feel that somebody in charge is on their side, in some deeper sense. This is the background for the Hiroshima projection.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

ART21: What is the role of the river and water, in the piece?

WODICZKO: Well, the water is not innocent. The river is as much a witness as the A-Bomb Dome building reflected in the water. It was in fact the river that became a graveyard for both people and buildings. The river was where people jumped to their death because they thought that it would help them to cool their burns, but in fact it only contributed to a quicker death. Those are the events or scenes recalled by some of the memorial projection participants and artists who were speaking through the building—as if they were the building, looking at the river and seeing all of this again—the bodies floating, the people jumping in. At the same time, the river continues its flow as if nothing has happened. There is fresh water coming. The river is like a tragic witness—but also a hope—because it’s moving.

The fact that both the building and the projection reflected themselves into the river (that is both a witness and a hope of change, a new life) somehow completed the picture. During the recording of the testimonies, one person was drinking water. As she was about to drink, I realized that perhaps I should suggest something aesthetically—that she pour the water back into the river. That was, maybe, the only aesthetic intervention in this project, which was met with agreement and support on the part of everybody in the studio. So, that’s why we left it at the end of the projection.

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 3 episode, Power. © Art21, Inc. 2005.

There’s one important aspect in the Hiroshima projection that might be true with all of my projections: the visibility of the texture of the surface on which the image is projected. The images are not projected on the white screen, but on the façades that are carved. They have their own iconic arrangements or texture, made of bricks or mortar. And this is important. There is an image; there is a building. There is a body of the person, projected; and there is a body of the building or the monument, animated. But it is also the skin of the building, the surface, which is seen as something in between. And that’s a very important protective layer—that separates the overly confessional aspect of the speech of those who animate the building and our overly empathetic approach towards the speakers.

So, that creates a distance, which is important for thinking—for recognizing that between them and us there is a wall. Any attempt to identify with the person is a danger. To say, “I understand what you went through,” is the most unacceptable response. The opposite may be more appropriate: “I will never understand what you went through.”

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2005 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.