Interview

“Vignettes”

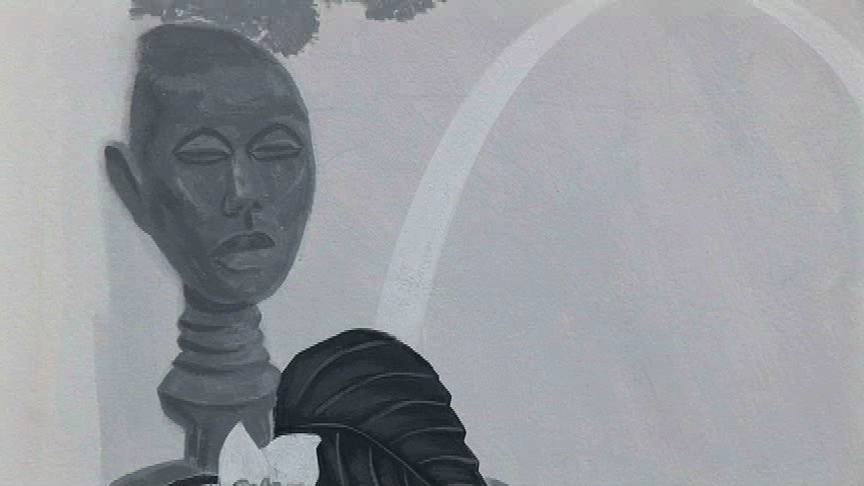

Kerry James Marshall. Installation view of Black Romantic at Jack Shainman Gallery, 2008. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive episode "On Museums." © Art21 Inc., 2008.

Kerry James Marshall discusses his relationship to museums during the installation of the exhibition Black Romantic at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, which features five paintings from the artist’s Vignettes (2003-07) series.

ART21: What’s the relationship between your series of Vignettes (2003-07) and what’s commonly referred to as post-black art.

MARSHALL: The work of African-American artists has for a long time been seen more as a kind of social phenomena instead of aesthetic phenomena. The social implications of the work — be it identity politics and things like that—seem to be privileged in terms of the way the work is received, as opposed to any kind of aesthetic project or intervention the work might be organized around. And so if you read any of the critique that was made around the Freestyle (2001) show at The Studio Museum in Harlem, you’ll find an undertone that seems to suggest that the mainstream critical world and art aficionados were tired of this whole identity politics and multiculturalism moment.

If you examine the subjectivity that a lot of African-American artists address, it often has a kind of cultural, social, political, or historical angle to it. So for the mainstream to suggest that it was sort of tired of having to address those kinds of issues, then, what’s really left for these artists to do if that’s something that’s meaningful to them? On some level, I thought maybe the only thing that was left to do was to make paintings about love. And to take a cynical approach to the concept of love, to the concept of the Vignettes (2003-07), so that they don’t seem to directly address the social and political issues that had been relevant to me and maybe to a lot of other artists who want to make work.

I began by looking at a lot of 18th Century French painting—Rococo work—like Boucher, Fragonard, Bouguereau, and other artists who themselves are also critiqued but critiqued for a lack of political depth in their work, for the frivolity of the work and for the work being kind of saccharine and sentimental and overly puffy and flowery. I started to take those two things and see if I could put them together—to preserve a certain element of the social, political, and historical narratives that are still important to me, but also to deal with the sentimentality, frivolity, and excesses that are embedded in Rococo painting.

Kerry James Marshall. Vignettes, detail, 2003-07. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive episode “On Museums.” © Art21 Inc., 2008.

ART21: The paintings are a sequence of images, an animation of sorts. Were you thinking viewers would relate to them cinematically?

MARSHALL: They’re cinematic only in that it’s a sequence of images that constitute one motion. And so in that regard, it is cinematic in a sense because you’re supposed to be constantly aware of the rotation of the two figures. It’s five phases of a 360 degree rotation. But that’s the only thing that’s constant in the group of works, because everything else around them is different. It’s like they are different pictures but they are a part of a single sequence of action.

ART21: Why are they painted predominantly in black-and-white?

MARSHALL: One of the reasons I use the grisaille technique in those paintings was to deny a bit of the Rococo. If you take a genre of painting that’s recognized for being pretty or flowery, but you want to start to do some other things, then you have to strip away some of those characteristics. One of the first characteristics is the over-investment in color that those pictures would have. So I stripped away the color, which reduces a certain amount of sweetness in the pictures. Black and white always tends towards a level of seriousness, and you can use it to avoid sentimentality when you’re dealing with highly keyed chromatic kind of relationships. The only color note in there is the cartoony pink in the hearts. The pink is a way of refusing to deliver on all of the points of which grisaille is supposed to deliver. And I chose to paint the hearts pink specifically to emphasize the disconnection between the overtly romantic imagery in the foreground and the historical or political imagery in the background.

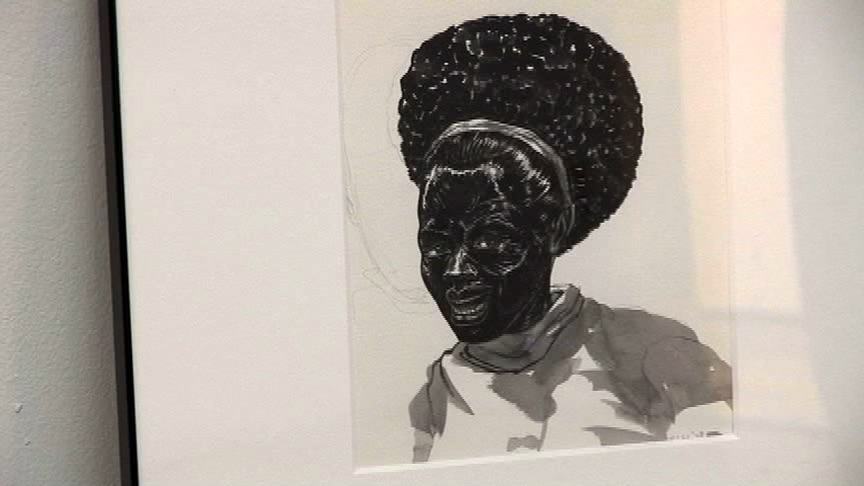

Kerry James Marshall. Untitled, 2008. Production still from the Art21 Exclusive episode “On Museums.” © Art21 Inc., 2008.

ART21: What advice would you give to younger artists?

MARSHALL: The drive to be relevant—not just for yourself and the people who like your work—has moved a lot of artists throughout time to do the kinds of things they do. If you look how artists became artists in the past, there were smaller numbers of people vying for positions in the royal courts and churches and atelier system. They didn’t have five thousand people coming through the system back then. But now we have these graduate programs at universities that are putting out thousands of credentialed artists every year. And so what are these artists trying to do? They are all trying to get a gallery show. They’re trying to get the grants. They’re trying to get written about in the newspaper. They’re trying to get their work collected. They’re trying to do all of those things so they can keep on making their work.

Now the only way you can do that really is to distinguish yourself from what everybody else in the field is doing. And so if you were taught while you were in school that being a part of the club — being one of many amongst other artists—that that’s somehow worthwhile, then how do you sustain your development and your productivity? What do you aim for?

Whatever it is you’re aiming for has to be judged by somebody outside yourself as having a kind of value. But if you just leave that to people who are out there, who somehow supposed to know more about what you’re doing than you do, then I think you are in a world of trouble. If you don’t have any mechanism to determine to some degree what your chances might be of achieving the kind of success as an artist you want to achieve, then you’re in deep trouble. And I think there is a lot that can be done. I think you can decide. And the way you decide is to know what it is artists are trying to do and what is meaningful to the discipline above and beyond what you think is meaningful to you as a person trying to express yourself.

This is why I say it’s not about self-expression. If it were really just about self-expression, then that would require a receiver who is so sensitively attuned to your sensibility that they are capable of recognizing an intrinsic value — not in what it is you’re doing, but who it is you are.

This interview was originally published on the Art21 Magazine in 2008.