Interview

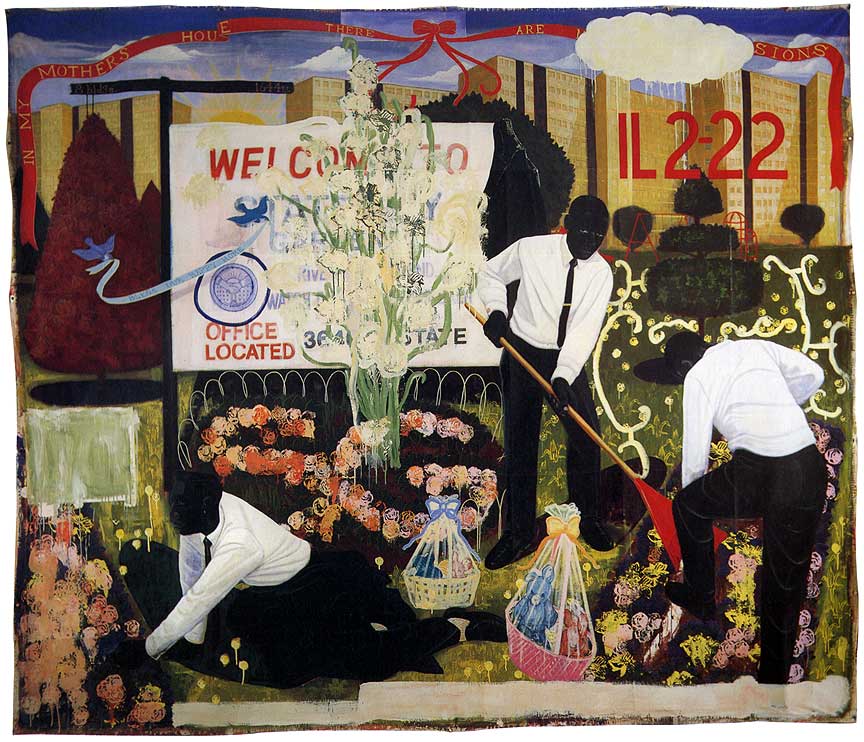

“Many Mansions”

Kerry James Marshall Viewing "Many Mansions" (1994) at the Art Institute of Chicago, 2000. Production still from the Art21 "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 1 episode, "Identity," 2001. © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Kerry James Marshall talks about the inspiration for his 1994 painting “Many Mansions,” acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago for its permanent collection.

ART21: How do you feel about this painting from 1994, Many Mansions, and about it being part of the Art Institute of Chicago’s permanent collection? Are you satisfied with it as a work, after all the other works you’ve produced between then and now?

MARSHALL: Well, how I feel about the painting and how I feel about it being a part of the Art Institute’s collection are two separate issues for me. Being in the Art Institute’s collection is actually a great honor for me. It was something that I actually strove for, ever since I decided I wanted to be an artist. One of the reasons I became an artist was because I was impressed with some things by other painters that I had seen, or other artists that I had seen. And so, part of my ambition had always been to be included in the museum collection, alongside all these other artists that I admired, and to be a part of the Art Institute’s collection, which has so many things that I really love, things that I come to see all the time.

But how I feel about the painting is another thing. I mean, it’s a painting that I like a lot. But when I come to look at my own work in the museum, I come essentially to analyze it, to check and see if it still works or holds up the way I thought it held up when I finished it. So, I come in to take a critical and analytical view of my own work. I mean, when you look at a painting like Many Mansions, which I finished back in 1995, and I consider where I am now, here in 2000, I’m so much further ahead of where I was then. Obviously, when I look back on it, I have to take into account that it was at a moment when I was at a certain stage in my development, when I was interested in issues that I may have fully explored by now. But, as a painting, I’m satisfied that it still seems as fresh to me now as it did when I completed it, five years ago.

ART21: Seeing it for the first time, there’s something about the painting that seems very familiar.

MARSHALL: Well, certainly the painting is built around what you could call a very classically Renaissance, architectural, or geometric structure. The most obvious thing you can see is this pyramidal, triangulated structure that the figures are fitted into. So, that’s one thing. If you look at the painting, you can really map out the grid on which all of those things hang, and then you look at the way the movement is created through these angles that cut across it. One of the reasons I used that structure was because, when I started out, the artists and works that I really admired—like Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, I think I mentioned that earlier—that whole genre of history painting, that grand narrative style of painting, was something that I really wanted to position my work in relation to. And so, in order to achieve a similar kind of authority that those paintings had, to fit them into a tradition of grandeur that those paintings represented, I had to adopt the similar structural format to develop my painting. And so, that’s what I did.

The subject matter seems in some ways less dramatic than the kinds of subjects represented in traditional history painting. But that’s also a part of what the painting is about. It’s about those figures being represented that way: the relationship between this representation of figures and the absence of those kinds of representations in that historical tradition of grand narrative history painting.

Kerry James Marshall. Many Mansions, 1994. Acrylic and collage on unstretched canvas; 114 × 135 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, Max V. Kohnstamm Fund, 1995. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

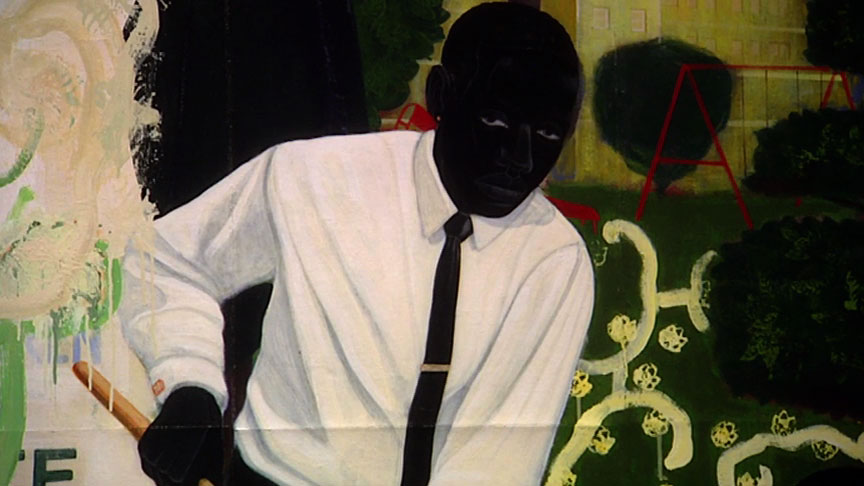

ART21: Why do you use such a flat black color when painting your figures?

MARSHALL: The initial development of that unequivocally black, emphatically black figure was so that I would use them as figures that function rhetorically in the painting. That kind of extreme is a rhetorical device that you go to when you want to emphasize or highlight a certain point. And one of the things that I had been thinking about when I started to develop that figure was the way in which the folk and folklore of blackness always seemed to carry a derogatory connotation. So, you saw a lot of very negative stereotypical representations of black people, especially in the nineteenth- and eighteenth-century images, and then even moving into the twentieth century. A part of what I was thinking to do with my image was to reclaim the images of blackness as an emblem of power, instead of an image of derision.

It also dovetailed with some things I was reading at the time. One of the books I was reading when I started to develop that image was Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man, in which he describes the condition of invisibility as it related to black people in America. The condition of invisibility that Ralph Ellison describes is not a kind of transparency, but it’s a psychological invisibility. It’s where the presence of black people was often not wanted and was denied in the American mindset.

And so, what I set out to do was to develop a figure or a form that would represent that condition of invisibility, where you had an incredible presence, but there was a way in which you could sometimes be seen and not seen at the same time. And what I started with was an image that was a black figure against a black ground, where there was only the slightest variation between the value of the figure and the value of the brown of the ground that it was painted against. The only way you could make a distinction, really, was that the temperature changed in the quality of the blacks. So, I’d paint a warm black figure against a cool black background. And that temperature change created enough of a perceptual difference that you can identify the figure at some angles, but at other angles it would completely disappear.

And so, it started out with the first painting I did way back in 1980, a painting called The Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self. It was the first time I had used this really highly stylized, simplified kind of representation of a black figure, but using that figure in concert with all of these compositional and stylistic devices that I had learned from studying Renaissance painting. And it was actually the first painting I had ever done where I felt like I was completely conscious of and in control of all of the aspects of the painting I was assembling to make the representation. I understood the effect of all of the devices I was using on the overall concept of the painting. And so, that painting was one that established the black figure as a mode of operating for me. It was highly stylized and incredibly flat, then.

Kerry James Marshall. Many Mansions, 1994. Acrylic and collage on unstretched canvas; 114 × 135 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, Max V. Kohnstamm Fund, 1995. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Production still from the Art21 “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 1 episode, “Identity,” 2001.

But over time, as my thinking about this became more complex, the representation needed a change and become more complex itself. So, it needed to start to be more than simply a one-dimensional or a two-dimensional kind of image, and started revealing a lot more subtlety and detail. And that’s where I arrived when I did a painting like Many Mansions, where the figures still are unequivocally black, because they’re simply painted with black paint. But there are highlights in the [paint] film that give you some variation and that reveals something of the individual identities of all of the figures represented there. You can’t say that simply because they’re painted with black paint that they all look alike.

And so, a part of this was to challenge certain stereotypical assumptions or representations of black people—that they can be represented by being called black as a monolithic group, although I can’t say that I believe for a minute that anybody really thought that, even though it’s a convenient way of categorizing a population, singling them out for political and social discrimination. It’s very convenient to think about people in blocks and in groups.

So, a part of what I was doing with this was to challenge some of that, too, by giving you what you think is a very simplified reduction initially, but upon closer inspection you have to come to terms with the fact that there are incredible differences embedded inside this apparently simplified and stylized representation. Each one of those figures is based on somebody, some particular somebody. Not a person that I want anybody to know, but what I do want you to know is that there is some difference between all of these representations, even as they seem to be simplified and reduced to what appears to be a stereotype.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.