Interview

“Buckets of Rain”

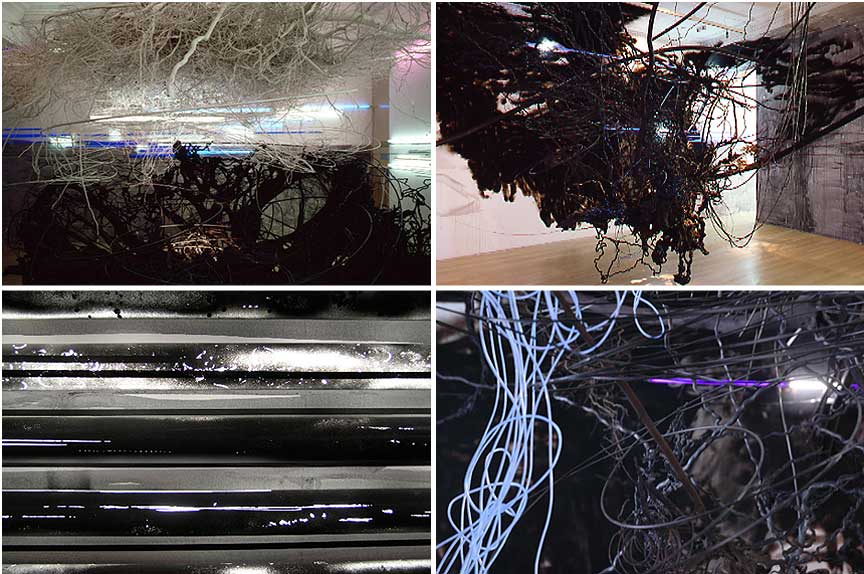

Judy Pfaff. Buckets of Rain, 2006. Wood, steel, wax, plaster, fluorescent lights, paint, black foil, expanding foam, and tape; 2 galleries, 153 x 245 1/2 x 209 inches and 153 x 228 1/2 x 165 inches. Installation view: Ameringer & Yohe Fine Art, New York. Photo by Zonder Title and Jordan Tinker. Courtesy of the artist and Ameringer & Yohe Fine Art, New York.

Artist Judy Pfaff discusses the inspiration for and elements of her 2006 installation piece, Buckets of Rain.

ART21: Can you talk about Al Held’s influence on your work and your show, which went up soon after his death?

PFAFF: Al Held was my teacher at Yale; we met in 1971. Our first sentence to each other was this: He said, “So, you’re the new dumb blonde?” and I said, “Who are you, the janitor?” He always demanded that I not be that dumb blonde, that I ask questions. His loss in my life was a big deal.

When we were finishing up the show, there were lots of things I actually hadn’t seen. There was a room off of the exhibition where the drawings were. There was this straight view past the drawing room into a far back room, where a lot of things were stored. And I remember that they had an Al Held painting. What was great about it was that it expanded the show into a whole other world. Plus, basically the show was for Al—Al and my mother, who both died within months of each other, and both were very big deals to me.

When you’re making something, you’re always focused on finishing it. And then, when you step back, you start seeing all of these things that you didn’t plan. You know, the sunlight that comes in at two o’clock, the shadow of someone walking by something. You’re sitting down, and you look up and see something that you hadn’t even remembered you put there. And you didn’t really put it there; it got there because of other reasons. That view through to Al’s painting—it was, like, “This is the end. I can leave now.” I always thought there were lots of connections with his work and my work. He didn’t really think that. I think he knew that we both liked complexity. There was a lot of geometry. There was a lot of torquing of space.

ART21: The emotional element of the installation surprised you?

PFAFF: Before, there have been a couple pieces that have been emotional. But most of the time, the work is about form and space, and I might be involved in building or architecture or a romance about being Chinese. Buckets of Rain was directly about a great loss or a kind of drama, and more about choices: black and white, life and death, good and bad, and the impact of that. It just embarrasses me even to think that way, that I did that. But, you know, I didn’t feel I had a choice.

Judy Pfaff. Buckets of Rain, 2006. Wood, steel, wax, plaster, fluorescent lights, paint, black foil, expanding foam, and tape; 2 galleries, 153 × 245 1/2 × 209 inches and 153 × 228 1/2 × 165 inches. Installation view: Ameringer & Yohe Fine Art, New York. Photo by Zonder Title and Jordan Tinker. Courtesy of the artist and Ameringer & Yohe Fine Art, New York.

ART21: How did you imagine people would move through this installation?

PFAFF: Well, you come off the elevators, and there’s a pretty big obstacle in front of you: this double cone. I assumed one would go to the right and then go straight to the back. So, there’s a kind of circumambulating, a kind of natural route. I always thought that it would be walked counterclockwise, because of the layout of the gallery. I think, if you entered from the other way, you would then walk clockwise. I hadn’t really realized this, but I think I always have a route in mind for how you walk—what the sequence of images will be.

ART21: It’s interesting that you think of the experience as sequential.

PFAFF: Yeah, I think there is a sequence. I think with this show that was important for me. Obviously I don’t put any directions in there; I just assume things. And then I watch people walk in, and they don’t do anything correctly. (LAUGHS)

ART21: There are different elevators that enter the gallery, so it’s a bit unpredictable exactly where a viewer will start from.

PFAFF: This is true. One of the joys is actually what the viewer will bring to it. So, if they reverse the sequence, it’s another story.

Most people are just like me. I go to a gallery; I open the door and think, “Do I like this; do I not like this? Am I intrigued enough to go through?” You usually give it a gestalt reading. If you get them past the first second, then you have a chance.

ART21: The show is very diverse, stylistically.

PFAFF: Stylistically it looks like it could be a group show of four different artists. Someone asked that; they said, “I like that piece of yours, Judy. Who did this one?”

ART21: Unlike many other artists, you aren’t attached to using any one material.

PFAFF: I’ve been very involved in not having a signature material. I think there is a signature style; it’s like handwriting. And I have a feeling that anybody who’s seen much of my work would probably recognize it as mine. But I don’t use the same materials. I like having different kinds of input coming in.

When I first came to New York, I had no money, obviously (no one had any money). And I had the Year of Aluminum Foil. I did the Year of Little Tiny Wire Structures. And then I would get a router or a tool, and it was the Year of the Router, the Year of the Jigsaw. It’s as if, with every new material, there’s actually a whole new image that comes about, from that color, from that material. I like that. So now, I’ve got all of these materials and all of these tools. There is a real range of how I would use steel, how I would use plasters and polyesters, different kinds of paints, from dyes to oils. I will use every variation and just about every surface and every material that I can imagine. I’m sure there are billions out there that I haven’t done.

Judy Pfaff. Neither Here Nor There, 2003. Mechanical tubing, wood, rigid foam, paint, and tape; 2 galleries, 153 × 245 1/2 × 209 inches and 153 × 228 1/2 × 165 inches. Installation view: Ameringer & Yohe Fine Art, New York. Photo by Zonder Title. Courtesy of the artist and Ameringer & Yohe Fine Art, New York.

ART21: Can you talk about your interest in Tibetan things?

PFAFF: I am the least meditative person I know. I’m the least calm person I know. I can’t breathe very well—you know, I mean “real” breathing. I think it must operate as a way to imagine things. It’s so other-than-me. I have a lot of books on Buddhism. There’s a Zen temple up here, and there’s a Buddhist temple in Woodstock, New York. Most of my friends are infinitely more thoughtful and centered than I am. I am not centered. Maybe it’s a desire. Because I know so little, I can use it as a motif. I have a feeling, if I knew more, I probably would stay away.

There was a moment—I guess I was sixteen or seventeen, when I worked on a farm that supported a school for Rudolf Steiner in England. And I was sort of banned from the school; that’s why they sent me to the farm part. But those holistic ideas of Steiner’s (and other great minds) have always interested me. So, I like to attach myself to them. It’s like guilt by association. Steiner’s ideas about education, music, holistic medicine, and architecture-based organic form—they seemed right to me, without knowing much about [them].

ART21: What was your experience inside this educational system?

PFAFF: Well, they don’t teach reading, writing, and arithmetic in the womb. (LAUGHS) They wait till you’re seven or so. So, you play. This is your education for quite a long time. You make music; you do plays. Play is the essential ingredient of that education for children—and it’s important for being an artist and being creative. Since I was pretty bad at reading and writing, I think it made sense to me that there were other ways of learning.

ART21: What else about your childhood do you think is significant in the work you do today?

PFAFF: I was a Cockney from London, and I came to America when I was about twelve and did not fit. I was quite unruly. So, I think probably there’s a fantasy or a romance in these ideas of real beauty and form coming out of a sense of the land I just love. I was such a scrapper. I still am. I still have a street urchin mentality, even though I know better. There’s no reason to have those feelings anymore, but I think you keep a lot of stuff from your past. So, I think those other kinds of glorious ideas and those really sane visions of the universe intrigued me because, probably, essentially I didn’t have that. The work has always had those two components in it. There’s organization and finesse, which always sort of surprises me, and then this roughness in it and a sort of put-together aspect, too. But I think both of those things interest me. One is probably more who I am, and the other is who I would like to be.