Interview

“Forest at Night”

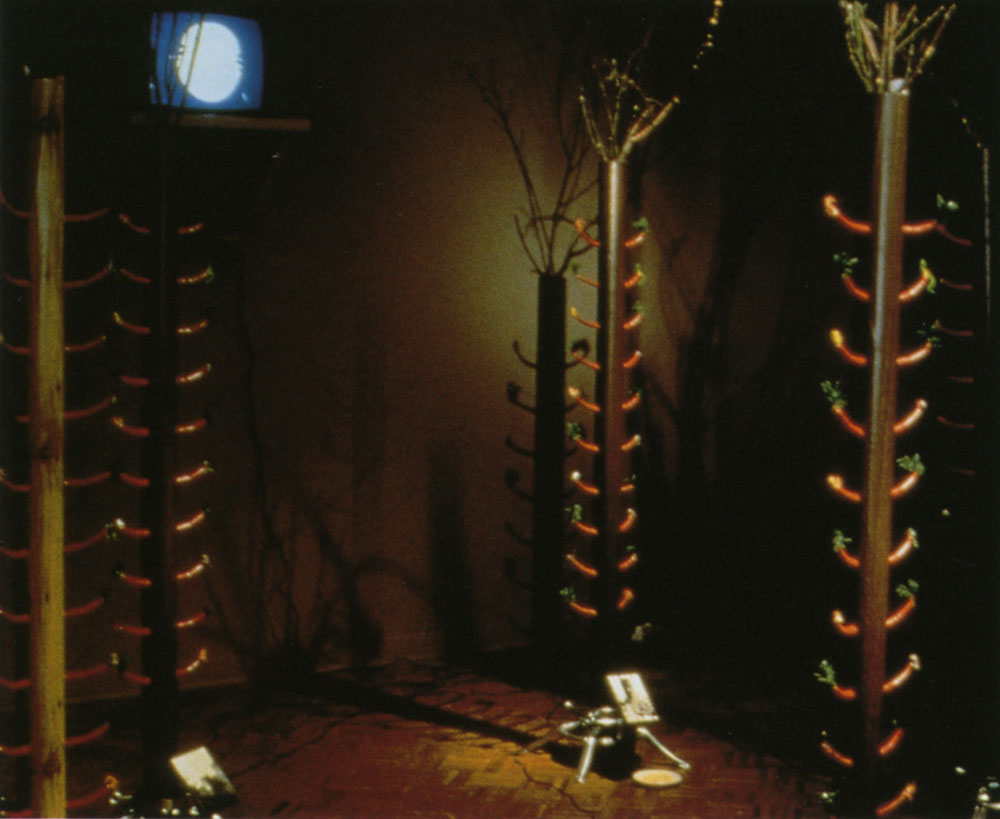

John Feodorov. Forest at Night, 1996-1997. Mixed media with video and sound; dimensions variable. Installation view: Sacred Circle Gallery of American Indian Art, Seattle, Washington . Courtesy of Sacred Circle Gallery.

Artist John Feodorov discusses his 1996 mixed media installation, Forest at Night.

ART21: Could you talk a little about the photographs in this work, Forest at Night?

FEODOROV: Living in the Northwest, clear-cutting is a hot button issue. You know, you’re trying to balance the environment with people’s lives—who have no other means of living, no other means of working. And so, what my wife and I did is: we went to a clear-cut and just took photos of some of the stumps. These trees are sort of an altarpiece for each one of those stumps that we saw in the forest. If you look at some Buddhist altarpieces—or even in Europe, if you go to some of those old graveyards in Paris—they’re not just stone set in grass. They are really pretty elaborate. Or Mexican altarpieces—they’re really beautiful things, and they really exalt the deceased relative. And that’s again the point of these. And it’s interesting because in Mexican altarpieces, they use a lot of kitsch objects because they put the objects there that the relative or the deceased person either used or liked—or something that reminds them of that relative.

I remember when I was a kid—when my grandfather passed away—I remember in the funeral, they were laying all these really beautiful pieces of jewelry, Navajo blankets, and pieces of pottery in the coffin. And I remember being really, really touched by that; and that had a profound effect on me. And so, I think that it’s coming from that as well. I think that it’s a reference point for that, as well, even though it’s kind of far removed from a tree stump. But, you know, it all ends up being squeezed out of the sponge in the end.

ART21: What about the tree stands?

FEODOROV: Well, these trees need to stand up somehow, so they provide a practical solution, but also we spray-painted them silver. They look like torture instruments. They look like these evil Inquisition tools; and again, you have that Christianity, coming to the New World and shackling and controlling the indigenous cultures. I think that it’s still going on—I mean, that kind of conflict between nature and technology—and that’s in this as well. I guess these are pretty loaded images. I mean, they’re very simple things, but you know, when you think about them long enough, it just brings into mind all these issues. And maybe that’s why people really respond to this piece. I don’t think that when I made them I was thinking that much about it, but the more I kind of just sat and looked at them, those issues kept coming up.

ART21: Why does anyone choose to become an artist?

FEODOROV: You’re asking hard questions. I don’t know. I ask myself that all the time. Would I be a lot happier if I went bowling? I mean, I see being an artist as sort of the same as being a bowler, anyway. It’s something that for some reason means something to me that’s indefinable. And I don’t consider myself very prolific. I hate making crap, you know. I hate making mediocre things. There’s so many mediocre things in the world, so I don’t want to contribute to that. So, sometimes it’s best that I don’t make things. But I think people are creative; people need to be creative, whether it’s making art or making babies. There’s that creative impulse, and people find creativity in different ways. Some people’s manifestations get called art.

John Feodorov. Forest at Night, detail, 1996-1997. Mixed media with video and sound; dimensions variable. Installation view: Sacred Circle Gallery of American Indian Art, Seattle, Washington. Courtesy of Sacred Circle Gallery.

ART21: Could you talk a little about the combination of elements in this work, like combining kitsch objects to suggest a landscape or forest? And, is there something in this work that addresses your own ideas about spirituality?

FEODOROV: Yeah, the branches are made of doll arms and are holding little plastic miniature toy animals—again, sort of reflecting the Disney mentality of nature that I think has evolved, just this century—I don’t think the twentieth century—or actually, we’re in another century now, aren’t we? Well, you know, in the nineteenth century, I don’t think Bambi would have received any sympathy; I think it would have been, “Good job for the hunters.” That would be real interesting to see how that kind of came about. I don’t know if it’s Disney’s fault—or whether they just really saw the market, or both—but Western culture has had a habit, I think, of [making everything like Disney]. I mean, again, during the Renaissance, they turned these frightening powerful angels into these cute chubby cherubs; born-again Christianity has turned the frightening, judging Jesus into a best friend, you know?

For some reason, Western culture likes to castrate the powerful, maybe because it doesn’t want to be less powerful than something else. That maybe it has to bring everything down to a level where—well, maybe it’s capitalism really—to where it’s a product, to where it’s something that can be controlled by purchase, controlled by owning it and by owning, even in art. Owning an object gives someone power over that object—turns the power that it once had into the only power it ends up having—maybe accentuating the pattern in the sofa. So, I think that is something that I really hate. Something that really comes out in my work—or I hope comes out in my work—is trying to infuse the intimidating back into the spiritual. Spirituality should be intimidating. It really should because people have no business being on a buddy-buddy basis with God. I think that’s just really stupid.

I think religion is the explanation of spirituality, and I think the mistake—well, I don’t want to call it mistake—I think the thing is that it’s not necessarily something that needs to be explained. I think it’s just sort of this hamper that you kind of throw things into. The spiritual to me is not really something that’s all that defined. I mean, you look at, for example, Navajo culture—I mean, no one sits around thinking, “Okay, we’re being spiritual right now.” It’s just part of the life. And it’s not like they lead spiritual lives in the way, I think, that most people think of spirituality, but it’s just: “That mountain range over there is Changing Woman’s Voice, and it solidified into rock; now it’s time to herd the sheep.” They live with it; they don’t have to think about it. They don’t have to think about it being spiritual, it just such a part of their lives that it’s not even considered. It’s not something that they have to think about, that “Now let’s be spiritual, because right now we’re not being spiritual.”

In Navajo healing ceremonies, you have all of the serious business going on in the hogan: the patient sitting on the sand painting, and the healers are doing whatever ritual it is. And then, outside they’re all dancing and having a great time, but that’s part of it too. It’s not just this somber thing. Or you think of Pueblo Indian dances, you know—they have clowns. And the clowns are making fun of the whole ritual, you know. But that’s part of the ritual. And I guess I kind of see myself in that vein, as sort of the clown in a way. I’m not debunking spirituality; I’m not making fun of it. I’m . . . well, yeah, I am. (LAUGHS) But the thing is that it’s only because I think it’s necessary. I mean, I think it’s a part of spirituality. I think it draws attention to modern Western alienation and this yearning for the spiritual—if not necessarily the spiritual, then some identity. When I said earlier that maybe being an artist is like being a bowler, I mean it is this search for meaning. And personally, I find meaning arbitrary, but it’s still necessary because it’s what keeps us going. You know, it keeps us motivated. And since, in our culture, we don’t necessarily go and have healing ceremonies done on us, to keep us rejuvenated spiritually, we find meaning in other things, whether it’s bowling or being an artist or watching the football game. That’s our community. That’s something that’s bigger than us, that will exist whether we are there or not, and that we’re allowed to be a part of. So, I think that’s maybe what I mean by spirituality. For myself, it’s more of where an individual fits in to the whole scheme of things, you know? It’s not very well defined, but it works.