Interview

“For 7 World Trade” and “Redaction Paintings”

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 4 episode, "Protest." © Art21, Inc. 2007.

Artist Jenny Holzer discusses her works For 7 World Trade, Redaction Paintings, and Truisms, as well as her love of clichés and comic relief.

ART21: How did you decide on the text for the World Trade Center piece?

HOLZER: I was invited to make something for the lobby at 7 World Trade Center. After much stewing, I came up with the idea of doing text in the wall—not memorial text but text about the joy of being in New York City. I despaired of writing for the piece, as I often do, and I came to poems by a number of different authors—everyone from Walt Whitman to William Carlos Williams, Elizabeth Bishop, and many more.

I stopped writing my own text in 2001. I found that I couldn’t say enough adequately, and so it was with great pleasure that I went to the texts of others. I’d begun practicing that for projects such as the one at the Reichstag, where I went to the stenographic records of what had been said by various political parties about everything from the boundaries of Germany to the role of women in society. After doing that, I started looking at this as a solution for projects such as For 7 World Trade.

ART21: You are happy to relinquish the text to others.

HOLZER: My pleasure is in reading and not in writing. I’ve read quite a bit for many years, and now the reading ranges from fiction to the declassified documents from which I’m making paintings. About the use of poetry in projects such as For 7 World Trade and in the projections—this is courtesy of my adult education, given to me by the American poet, Henri Cole.

I’ve spent a fair amount of time alone, on my work, and so it’s with real joy that I go to other people to make something larger than I could have done solo. I’ve liked working with other artists on projects like Sign on a Truck and collaborative project shows. I’m heavily dependent on consultants for these poetry projects or for the ones that have to do with history.

It’s clear that my work is not poetry. Occasionally people have charged me with it not being poetry, and they’re correct. I’ve always been certain that it’s not. It might take the shape of a poem, but that has nothing to do with literature. It has to do with the demands of the medium on which I place it. The space at 7 World Trade Center demanded that I fill the lobby—in particular, the glass wall—and I thought that the text should float by. To make the piece, I had to look at a number of drawings and renderings, make quite a few site visits, and not only stare at the space but also walk it and feel it. After innumerable visits, I finally had some confidence in what I should do next. I like to make pieces that fill interiors. Glass walls are my friends because they let people outside see what’s happening inside.

With the projections, it’s a different process. I will project light and words on the exteriors, on the facades of buildings, and then sometimes will see the text creep into the offices and the public spaces inside. I hope the installations are atmospheric. I want color to suffuse the space and pulse and do all kinds of tricks.

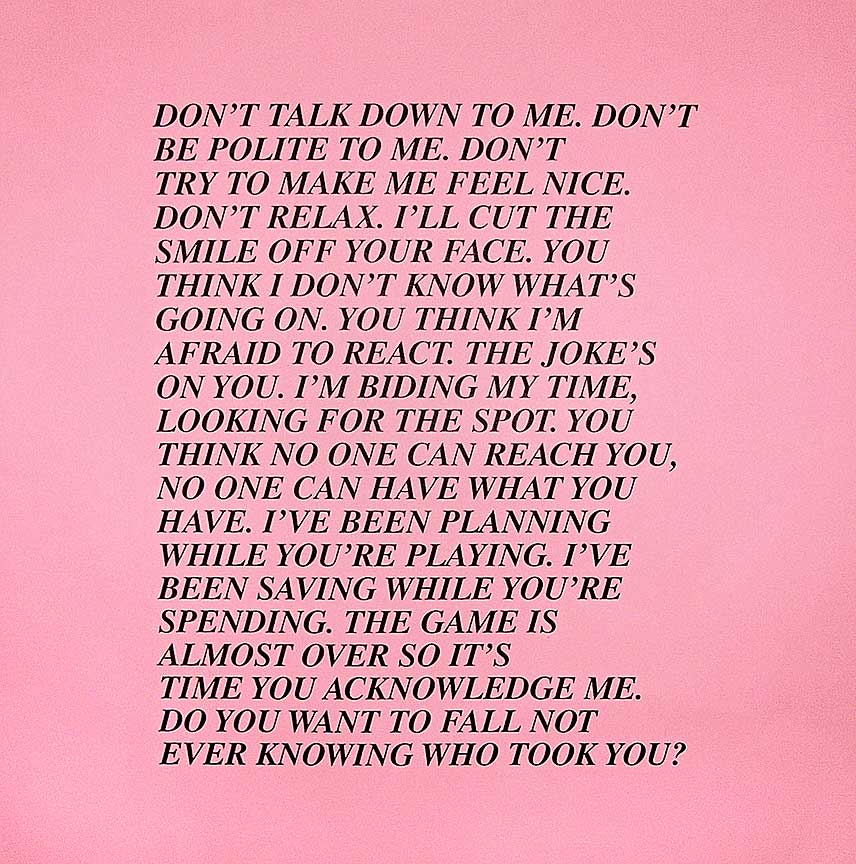

Jenny Holzer. Inflammatory Essays, detail, 1979–82. Offset poster.. Text: “Inflammatory Essays” (1979-1982), Photo: Mindy McDaniel, © 2007 Jenny Holzer, member Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Art21: So, you’re a magician?

HOLZER: No, I’m not a magician. (LAUGHS)

The big installations not only include the creation or choice of the text, but they also have much to do with filling the space and programming the electronics. That programming includes pauses, flashes, phrasing, and more. I really like the programming aspect. I was a typesetter, and typesetting is not unlike programming. You have to make text correct, complete, and pretty—and fitted. The presentation needs to make sense with the content and then needs to engage people. The poetics come from poetry by others, not from myself, but what I can contribute is something like a visual poetics that can have to do with the color, the pauses, and the omissions. I don’t know how to program, so I’m reliant on others to do it, but I participate. We often decide what to do in the place, at the site of the installation, not in advance. We will have our ideas about what’s going to happen, and then we go and see if they were right. And often they aren’t, and we’ll fix them. There are many ways to have it wrong—if it’s boring, if it seems wrong for the content, if it doesn’t complete the space—and often you can’t tell until you’re there.

ART21: Why did you stop writing?

HOLZER: It has always been hard for me to write, as I think it is for anyone who wants to write well. I was pleased to leave it, and I have no idea whether I’ll write again. One reason why I stopped was because I tend to write about ghastly subjects. So, it’s not just the difficulty of having something turn out right, but it’s also the difficulty of staying with the material long enough to complete it. It’s necessary to be emotionally engaged when writing about these topics. It’s exhausting.

I know that my researchers and I have had to stop, at various times, reading the material for these redacted paintings. Sometimes it’s a relief to come to the pages that are wholly blacked out because then, for at least a page or so, you don’t have to read what was there. The redaction paintings include many pages that are almost completely blacked out. Before the documents were released, the government blackened or excised portions for security or unknowable reasons.

ART21: Do you ever use texts written in the first person?

HOLZER: Often, I’ll use the first person in my work. I will assume that voice. Or I will represent many people in the first person. There are lots of I’s and You’s in the Inflammatory Essays, but they’re not me. They’re many different voices on a host of unmentionable subjects. I’m present in the choice of the subjects addressed in the work, in the form that they take, and the places they go.

There’s a reason I’m anonymous in my work: I like to be absolutely out of view and out of earshot. I don’t sign my work because I think that would diminish its effectiveness. It would be the work of just one person. I would like it to be more useful than that—to be of utility to as many people as possible. I think if it were attributed to me, it would be easier to toss. I want people to concentrate on the content of the work and not “who done it?”

ART21: Can you talk about your project called Truisms?

HOLZER: The Truisms were perhaps an overly ambitious attempt to make an outline of everything that I wanted to do. I’m not sure I knew that at the time I wrote them, but that’s what I’ve come to recognize. I wanted to have almost every subject represented, almost every possible point of view, and then I had to sort out what those sentences should appear on. That turned out to be the street posters. Subsequent series had different demands because they had to fit in any number of places. I had to find the right medium, be that stone or electronics. So, I tried to sort this out as I went. I’m afraid to talk about values these days. Usually, any time values are invoked, it’s to dismiss or maybe incarcerate somebody! I do make work that focuses on unnecessary cruelty, in the hope that people will recoil. I would like there to be less fear and cruelty.

And I’d like to think I have some plain old empathy, too.

ART21: Could you expand on that statement?

HOLZER: I liked that one. That’s the first sentence I’ve liked. (LAUGHS) I’ll stand on it.

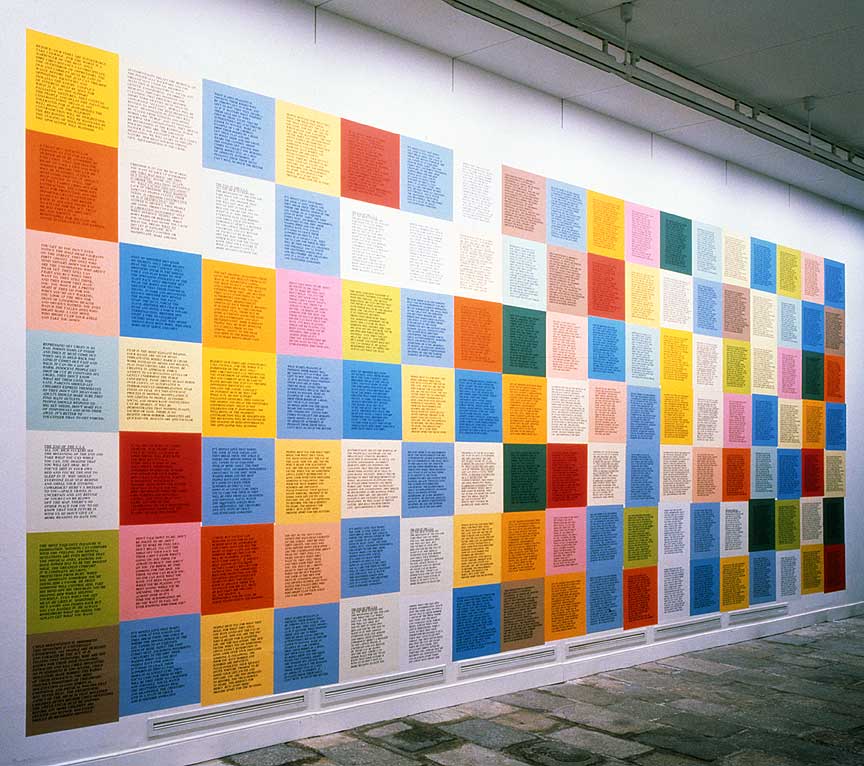

Jenny Holzer. Inflammatory Essays, 1979–82. Offset posters. Installation view at Fundació Caixa de Pensions, Barcelona.

Text: “Inflammatory Essays” (1979-1982), Photo: Miguel Bargallo and Tony Coll, © 2007 Jenny Holzer, member Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

ART21: How do you go about obtaining the politically based texts?

HOLZER: I’ve only worked with material that already has been released. I have not done any Freedom of Information Act requests on my own because there’s so much to sift through that’s already out there. I draw on everything, from the National Security Archives collection to old material from the FBI’s website, to postings by the ACLU and a number of other places. I go looking all the time.

I’ve focused on documents about the conflict in the Middle East, both the last Gulf War and this one—that’s one group. I’ve also gone back to older things for comic relief, such as the FBI following around Alice Neal because she was a Communist.

ART21: Any other examples of comic relief?

HOLZER: One other funny thing was the FBI interviewing Marian Anderson’s neighbors to see if she was a good person—and having people testify that she was because when she came home from tours, she would do the dishes, and this made her A-OK. I guess that’s funny.

I have one thing . . . there was much ink spilled about Brecht being observed in his pajamas, spending a lot of time at the typewriter.

ART21: You like clichés.

HOLZER: I love them.

ART21: Can you talk more about why you love them?

HOLZER: Clichés are truth telling, time tested, and short. These are all fine things in words. People attend to clichés, so important subject matter can be disseminated. Clichés are highly refined through time.

ART21: Talk about the handprint paintings.

HOLZER: I made a number of paintings of redacted handprints. We have found some handprints of dead people, handprints that were made postmortem, and these are extraordinary. You’ll see that sometimes the handprints are almost completely muddy because the person pressing down didn’t know how hard to press. I turn these handprints into paintings, with apologies to the dead, and then move to make them as precise, as clear as possible. Most of the paintings are only three times page size because I wanted them to refer to the actual documents. Other ones I made very tall, so that they would be physically overwhelming.

ART21: Are these works a form of protest?

HOLZER: Presenting the documents about torture is a protest. Showing love poems is not.